“We decided to fight in courts instead of on the streets,” Sharon Lavigne, founder of RISE St. James, explained to me on a call, describing her faith-based community organization’s latest legal victory. The decisive free speech win follows other recent notable milestones for environmental justice advocates in the petrochemical and refinery-lined river parishes between Baton Rouge and New Orleans — an area known as “Cancer Alley,” where Lavigne lives.

On November 17, a week before Thanksgiving, Tulane Law’s First Amendment Clinic, announced a favorable settlement on behalf of RISE. St. James after a two-year legal battle against the St. James Parish town of Gramercy and its mayor, Steve Nosacka, an outspoken supporter of the oil and gas industry.

Back in the fall of 2020, RISE. St. James was planning to hold a protest march in Gramercy in an effort to stop an industry-friendly ballot initiative. The time was marked by heightened racial unrest following the murder of George Floyd, which sparked Black Lives Matter protests to spread spread across the country, including in New Orleans.

Two days before RISE St. James’ march was set to take place, Lavigne learned that the town required her organization to post a $10,000 bond to obtain a permit for the march, money the group didn’t have access to on short notice. She and the other protest organizers weighed whether to hold the protest in Gramercy without a permit, she told me, but reasoned if they got arrested at the start of their march, it would prevent them from achieving their goal of helping to defeat Amendment 5, one of the ballot initiatives in the upcoming election. That amendment, if passed, would have allowed manufacturers to negotiate lower tax bills with local governments, giving the already dominant petrochemical industry a way to permanently avoid paying property taxes.

RISE St. James and the group’s supporters who planned to participate in the protest, decided to get a permit to march in the neighboring town, Lutcher, and challenge Gramercy at a later date in court for trampling on their First Amendment rights.

So on October 17, 2020, the date of the planned protest, members of RISE St. James and its supporters marched without incident in Lutcher instead of Gramercy. Those at the front held a Black Lives Matter banner, as a couple dozen marched to spread awareness about Amendment 5, chanting intermittently, “Say no to Amendment 5” and “Black Lives Matter.”

And on November 3, voters in Louisiana overwhelmingly rejected the ballot initiative. A few days later, RISE St. James, with the help of Tulane’s law clinic, fought to protect their constitutional right to protest in Gramercy.

In a settlement announced this month, Gramercy agreed to pay $45,000 for legal fees plus $100 for damages. It also walked back restrictive rules on its books related to marches. Now citizens and groups like RISE St. James are exempt from the town’s $10,000 march permit bond requirement if they can prove they are unable to afford it, removing a financial barrier from the constitutionally protected right to protest.

“The law is on our side,” Lavigne told me. RISE St. James plans to keep pursuing environmental justice in the courts if regulators continue to put the needs of the fossil fuel industry above the needs of fenceline communities in Cancer Alley. Lavigne expressed gratitude for the progress her group and other partnering organizations have already made but acknowledged there are still major battles ahead.

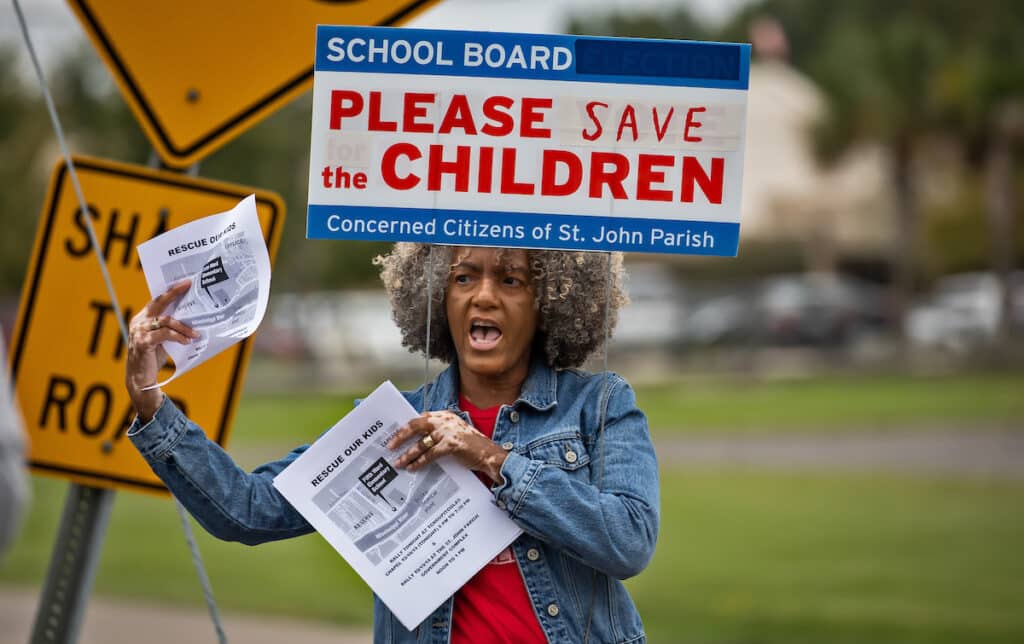

“This Thanksgiving, we can all celebrate and be thankful that our work has come to fruition,” Robert Taylor, the founder of Concerned Citizens of St. John, told me, reiterating Lavigne’s sentiments. “I think we are in a great position to really move forward and get important overdue, life-or-death stuff done in Cancer Alley.”

Taylor, a retired general contractor, was driven to form the community group in 2016 after learning that the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) had determined that those living in six census tracts closest to the Denka Performance Elastomer plant in St. John the Baptist Parish have a lifetime risk of cancer from air pollution that is 800 times higher than the national average. He and the other founding members of the concerned citizens grassroots organization find it unacceptable that their community is still subjected to levels of chloroprene exposure well above the EPA’s recommended emissions limits.

The Denka facility, which produces the synthetic rubber neoprene, is one of numerous petrochemical plants in predominantly Black fenceline communities along the Mississippi River, which face some of the country’s highest risks of cancer from air pollution, according to EPA data.

“I’m so thankful to the groups that are with us in this fight,” Taylor, who often works in tandem with RISE and other environmental justice advocates, said. His group remains focused on protecting the children at the Fifth Ward Elementary School, which shares a fence line with the Denka plant, from further exposure to chloroprene, a likely human carcinogen.

The current push to expand the petrochemical industry and increase LNG exports would lock in an increased demand for natural gas at a time of worsening climate change. Every stage of natural gas production and distribution releases methane pollution, a powerful greenhouse gas. Because of those methane leaks, consuming more natural gas spurs ever-faster and more dramatic climate changes.

This growing awareness of the petrochemical industry’s role in contributing to climate change has also led to growing awareness of the environmental racism faced by fenceline communities in Cancer Alley. Their fight for environmental justice is garnering worldwide attention and an expanding network of supporters. In August, Taylor and other Cancer Alley residents traveled to Switzerland to tell a United Nations human rights body about their experiences with the expanding petrochemical industry and systemic environmental racism in south Louisiana. And earlier this month Lavigne, along with members of RISE St. James and other advocates from Louisiana traveled to the UN climate summit in Egypt to tell the world that their communities are not sacrifice zones.

In January, Earthjustice and the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law submitted a civil rights complaint to the EPA on behalf of the Concerned Citizens of St. John and the Sierra Club. The complaint calls out the Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality (LDEQ) and Louisiana Department of Health (LDOH) for their handling of air pollution and associated health impacts in St. John the Baptist Parish, alleging that the state agencies failed to protect the majority Black parish. In February Tulane’s Environmental Law Clinic filed a similar but separate civil rights complaint to the EPA against LDEQ on behalf of RISE St. James and other community groups.

Those civil rights complaints helped prompt the EPA to open a civil rights investigation into the LDEQ and LDOH. On October 12, the EPA sent a 56-page letter of concern to those two agencies summarizing its initial findings. The highly critical letter states that the EPA’s analysis so far “raises concerns” about the agencies’ behavior, which “may have an adverse and disparate impact on Black residents” in Cancer Alley.

The EPA’s letter cites multiple examples of DeSmog’s reporting, which includes documentation of Cancer Alley advocates’ many protests over inaction and videos of the LDEQ Secretary’s comments that are “inconsistent” with the agency’s claims about its responsibilities to regulate chloroprene.

Greg Langley, LDEQ spokesperson, told DeSmog “We are in discussions with EPA about the Title VI [civil rights] complaint. We do not have a comment about it.” And LDOH communications director Alyson Neel said, “The Louisiana Department of Health takes these concerns very seriously and is committed to health equity — which is why we are fully cooperating with the EPA’s investigation into Denka Performance Elastomer.”

The Denka Performance Elastomer plant continues to challenge the EPA’s assessment of the health risks related to chloroprene emissions, and Jim Harris, spokesperson for the plant, asserted to the Lens, a local independent news source, that there is no evidence of increased levels of health impacts near the plant in St. John the Baptist.

But a report based on a health study conducted by the University Network for Human Rights outlines evidence that show a pronounced risk of cancer and other negative health effects due to toxic chemicals in the air.

Last November when EPA Administrator Michael Regan visited the Fifth Ward elementary school on his “Journey to Justice” tour, he promised the Concerned Citizens of St. John that he would use all the tools in his toolbox to protect the community’s children. Taylor says he hopes that the growing public scrutiny of the environmental racism against Cancer Alley residents will force regulators to finally protect the community’s children from further chloroprene exposure. While he and members of his organization appreciate additional air monitoring and health studies, they don’t believe any more evidence is needed before actions are taken to protect their children, whether that means sending them to a school outside the parish farther from the Denka plant’s chloroprene emissions, or shutting the plant down.

Another source of hope for environmental justice advocates in the region came this September, with the news that two proposed petrochemical complexes in St. James Parish, South Louisiana Methanol and Formosa’s Sunshine Project, faced further setbacks.

On September 1, the St. James Parish Council turned down South Louisiana Methanol’s request to rezone a neighborhood where the company purchased land to build its proposed $2.2 billion dollar complex. But just over a week later, the nearly decade-long fight over the project came to an end when the company failed to meet an LDEQ deadline. As a result, the agency withdrew the company’s application to modify its existing air permits.

And on September 12, Baton Rouge District Judge Trudy White ruled in favor of RISE St. James and several other environmental groups in their legal challenge to LDEQ’s decision to issue air permits to Formosa Plastics (FG LA LLC) for its proposed $9.4 billion petrochemical complex in St. James, less than two miles from Lavigne’s home.

Judge White found that, by the company’s own calculations, the facility’s pollution would be in such high quantity and so harmful to the surrounding air that even brief exposure would pose a threat to human health in an area already notorious for higher-than-average cancer-causing toxins. And that if the complex were up and running, the air in parts of St. James Parish would violate the EPA’s standards for soot and ozone-forming nitrogen dioxide.

“Simply put, LDEQ failed to address the core problem posed by FG LA’s model, the only record evidence on point: people working, living, travelling, or recreating in St. James Parish could suffer serious health consequences from breathing this air, even from short-run exposure,” White wrote in her decision. “Because the agency’s environmental justice analysis showed disregard for and was contrary to substantiated competent public evidence in the record, it was arbitrary and capricious.”

LDEQ’s Langley declined to comment on the district court’s ruling, citing ongoing litigation.

However, Formosa Plastics group and its FG LA unit have shown no sign of backing away from their proposed plans to build the massive petrochemical complex in St. James Parish.

“FG respectfully disagrees with Judge White’s conclusion,” Janile Parks, FG LA’s spokesperson, told DeSmog in an emailed statement. “We believe the permits issued to FG by LDEQ are sound and the agency properly performed its duty to protect the environment in the issuance of those air permits.” She added that the company “intends to construct and operate [the project] to meet all state and federal standards.”

Environmental justice advocates hailed White’s ruling as groundbreaking, because it was the first time a state district court has ever thrown out an LDEQ air permit on environmental justice grounds.

But even with such victories, proposals for new fossil fuel projects, each seemingly more massive in scale than the next, keep popping up.

On November 16, Chevron Phillips Chemical and Qatar Energy announced plans to build an $8.5-billion petrochemical plant on the Texas side of the Sabine River at the Louisiana border, an area where a growing number of LNG export facilities are being permitted.

The environmental justice community groups in Cancer Alley are quickly learning that victories in the movement are temporary. After all, Formosa is appealing Judge White’s decision.

“I still feel like we were victorious against Formosa,” Lavigne told me. “They’re trying to find ways that they can go around the law and get this victory from us, but it’s not going to help. We not going to lay down and roll over. We’re going to continue to fight.”

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts