The push to sell “blue hydrogen” as a clean energy fuel — which experts have called a misleading rebrand of fossil fuels — hit another setback this month.

Climate provisions in the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 are bringing new economic headwinds to the gas-derived hydrogen fuel’s prospects. However, many companies invested in the continued existence of the natural gas industry are not giving up on the effort, presumably because blue hydrogen promises to extend the life of natural gas producers.

DeSmog has mapped for the first time the major U.S. players in the blue hydrogen sphere — and natural gas is a common denominator.

Blue hydrogen is the industry name for hydrogen, an energy carrier, that is created from natural gas but would theoretically employ carbon capture technology to prevent the resulting carbon dioxide emissions from entering the atmosphere. However, as DeSmog has previously reported, carbon capture has failed to work in blue hydrogen production facilities at rates that would qualify the hydrogen as “clean.”

We’re already planning to build a #hydrogen facility in Texas and are conducting a study in the U.K. to assess the feasibility of producing blue hydrogen at scale. Yvonne Dacey, the project manager heading a hydrogen production in the U.K., explains: pic.twitter.com/kEJZVXxBRY

— ExxonMobil (@exxonmobil) August 3, 2022

Blue hydrogen’s supporters have argued that the world needs the gas-dependent fuel until it could scale up affordable clean hydrogen (known as “green hydrogen,” which uses renewable energy and does not produce any carbon dioxide or methane emissions).

It was a compelling financial argument, and in January 2021, when DeSmog first reported on efforts to establish a hydrogen economy in the United States, energy analysts were estimating that green hydrogen might take until 2040 to become economically competitive with gas-derived hydrogen.

That same month, Shell wrote on its website: “Whilst green hydrogen is the ideal aspiration for a low-carbon energy future, that technology has a number of years to go before it is of a competitive price range.”

Since then, those expectations have been completely upended by a combination of factors, including the rapidly falling cost of renewable electricity — which makes green hydrogen cheaper — and the sizable increase in the price of natural gas — which makes blue hydrogen costlier.

When the push for blue hydrogen began in 2020, the price of natural gas in the United States averaged $2.05 per million British thermal units (MMBtu). Now, it’s more than $9/MMBtu — a quadrupling in price. It’s clear now that not only is blue hydrogen not truly clean, but the economics don’t work. Even Shell has changed its tune: Earlier this month, the renewable energy publication Recharge reported that the oil company’s CEO said soaring gas prices mean blue hydrogen will not be able to compete economically with green hydrogen “for some while.”

What’s more, the high price of natural gas isn’t likely to change anytime soon, according to Clark Williams-Derry, a financial analyst at the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis. “[There is] reason to believe that there will be sustained high prices for the next three to four years, that we’re going to be in a much higher price regime,” Williams-Derry told DeSmog.

That was all before the sudden emergence of the Inflation Reduction Act, which is a game-changing setback for the blue hydrogen industry. The Biden administration’s signature climate and tax law includes production tax credits that will likely make the green hydrogen produced in the United States the cheapest form of hydrogen in the world. As Recharge notes, for methane-derived hydrogen to be cost competitive now, the methane would have to cost nothing, even before adding in the additional cost of carbon capture. But the bill, which was overseen by the fossil fuel-friendly Sen. Joe Manchin (D-WV), also includes support for methane-based hydrogen, offering production tax credits for any producers of low-emission hydrogen. Initial industry reaction, however, suggests the bill favors green hydrogen production.

BNEF thinks $3/kg subsidy for green H2 projects is worth ~$1.91/kg dollars on a levelized basis. Can bring down avg. US cost of green hydrogen down to $2/kg by 2023. By 2030, they think levelized value of PTC would actually be > their base view for unsubsidized green H2 costs. pic.twitter.com/e4RPxbM3Y9

— Shanu Mathew 🌎🌳⚡️ (@ShanuMathew93) August 16, 2022

The Bigger Goal: Preserving Natural Gas Infrastructure

This development is a major blow to the fossil fuel industry’s efforts to build out blue hydrogen as it undermines the main argument — that blue hydrogen is cheaper. However, the climate bill does not derail the industry’s larger goal of mixing hydrogen of any kind into the existing natural gas pipeline system, which would help both to keep burning gas and to lock in pipeline infrastructure investments.

From plans for hydrogen homes by SoCalGas to tests to blend 5 percent of hydrogen into existing natural gas power plants like Long Ridge Energy in Ohio, proponents of blue hydrogen say the fuel should be used everywhere natural gas is currently used, including home heating and combustion in power plants to produce electricity, and that existing natural gas pipelines should distribute it. This strategy makes a lot of sense for companies already invested in the global natural gas industry; it keeps the world hooked on natural gas.

But the world could stay hooked on natural gas if the industry convinces investors and policy makers that blending green hydrogen into the existing natural gas system is a good idea (it isn’t). That’s because using hydrogen in existing natural gas pipelines increases leak and explosion risks, hydrogen for home heating is inefficient and expensive, and using renewable electricity to make green hydrogen to then burn it to make electricity is highly inefficient.

In July, DeSmog published a map of the lobbying actors trying to create a hydrogen economy in Canada, highlighting the entities behind a big push for blue hydrogen projects, including Shell. Last year, DeSmog mapped the EU hydrogen lobby as well. Below is a new map from DeSmog showing the players behind the same efforts in the United States.

Credit: Gaia Lamperti

The majority of the companies on this map — like ExxonMobil, Air Liquide, and Sempra Energy (parent company of SoCalGas) — profit from the existing natural gas industry, whether producing natural gas, distributing it in pipelines, or burning it in power plants.

“When it comes to the fight against global warming, all options must be considered,” Air Liquide told DeSmog. “In line with its Sustainable Development objectives, Air Liquide is committed to supporting the development of both renewable and low-carbon hydrogen at competitive costs.”

The Financial Times recently highlighted Shell, BP, and Chevron’s U.S. lobbying efforts on behalf of all types of hydrogen from their position as members of the Clean Hydrogen Future Coalition, whose website touts blue hydrogen as “clean.” FTI Consulting, which has run numerous influence campaigns for the oil and gas industry, and the Hydrogen Council, a trade group whose founding members include Europe’s top fossil fuel producers, are both instrumental in the global and U.S. hydrogen lobbies. The seeds were sown in the EU, and it is roughly the same cast at the ground level in the United States.

The map also includes companies, like Mitsubishi, that at first glance, seem unlikely candidates to support the blue hydrogen economy. Yet, as early as January 2019, Seiji Izumisawa, President & CEO of Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, stated in an interview published on the Hydrogen Council website that hydrogen “helps decarbonize traditional power plants.” Mixing green hydrogen into the fuel supply of gas power plants does reduce carbon emissions, but those reductions are small; using blue hydrogen instead would likely result in 20 percent higher methane emissions than just burning gas directly for heat, according to a 2021 study.

This has not derailed plans for large blue hydrogen projects in the United States. Air Products* has plans to build a $4.5 billion blue hydrogen facility in Louisiana. Mitsubishi has signed an agreement with Bakken Energy, LLC for a blue hydrogen project in North Dakota (and with Shell for a blue hydrogen facility in Canada).

Earlier this month, Bill Newsom, the CEO of Mitsubishi Power Americas, promoted hydrogen for “power generation” at a Reuters event.

It’s easy to understand why. Mitsubishi also sells turbines that are used in traditional natural gas power plants. If the world stops using natural gas to produce power, Mitsubishi no longer has a gas turbine business. If the world switches to using hydrogen in all of those power plants (which require new hydrogen-ready turbines made by Mitsubishi), the turbine business has a bright future.

Mitsubishi did not respond to questions from DeSmog.

At the Reuters event, Newsom repeatedly stressed the desire to reuse natural gas infrastructure for hydrogen. “What we want to do is look at how can we inject hydrogen into these existing pipelines,” he said, adding that blue hydrogen “has a very viable path.”

Newsom went on to suggest that the world needs blue hydrogen until green hydrogen is available, despite the fact that Mitsubishi is a partner in one of the largest green hydrogen projects in the United States, which just received a $504 million loan from the U.S. Department of Energy. This project is touted as a clean hydrogen project, but the green hydrogen it produces will be blended with methane until at least 2045.

Such a move offers much lower emissions savings than just using renewables or straight green hydrogen. It makes little sense — unless you are in the turbine business.

Creating green hydrogen requires lots of electricity derived from wind, solar, and other renewables. Using this renewable energy to create green hydrogen that is then burned to create electricity is incredibly inefficient. For the same reasons, using any kind of hydrogen to heat buildings makes no economic sense.

Another reason plans to burn any kind of hydrogen for power are suspect is that Newsom admitted that burning 100 percent hydrogen in power plants currently isn’t possible; methane is still required.

In the majority of cases, the most economical and climate-friendly approach is to directly power electric cars and heat buildings with renewable electricity, rather than using it to create green hydrogen.

The world already uses a lot of hydrogen, mostly to refine oil and produce fertilizer for agriculture. The majority of that hydrogen is made from natural gas and that process is responsible for 2 percent of the world’s carbon dioxide emissions.

The world still needs green hydrogen to replace the current fossil fuel-derived supply of hydrogen, even if all other areas of the global economy could be decarbonized with renewable-powered electricity. It also is likely the best option for decarbonizing the steel industry, and is showing promise for aviation and shipping applications.

The recent developments making green hydrogen a source of affordable clean energy are welcome, but in no way do they support the argument that burning green hydrogen for power or heat is a realistic path to reducing emissions.

Blue Hydrogen Makes the Methane Emergency Worse

The natural gas industry has already tried to convince the world that natural gas is a clean form of energy — but those past public relations efforts were not accurate. Yes, burning natural gas for power creates fewer carbon dioxide emissions than burning coal, but that is only part of the story. Producing natural gas also releases methane, a potent greenhouse gas that has contributed approximately 40 percent of total climate warming to date. When methane emissions are included in the calculations, natural gas becomes as dirty as coal.

US & EU agree 30% methane cuts in a sign the world is waking up to the methane emergency. However @IPCC_CH scenarios modelled in AR6 suggest we need cuts of around 75% to plateau at 1.5C.

— PlantBasedTreaty (@Plant_Treaty) November 2, 2021

We need a pledge which includes solutions 👉#PlantBasedTreaty

https://t.co/pMH0qInOjE

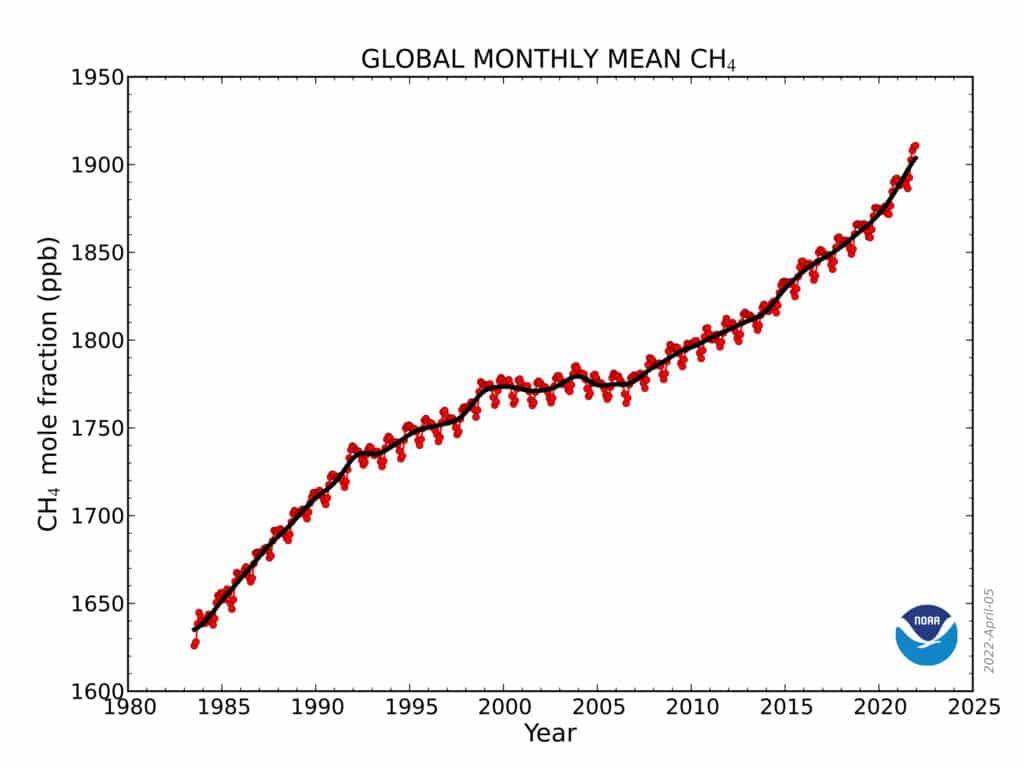

Selling gas-derived hydrogen as “clean” is especially risky because of the methane emissions it would release and the urgent need to curb those emissions to avoid catastrophic warming. Switching the world to blue hydrogen as an energy and heat source would mean continuing to support the oil and gas industry’s plans to increase natural gas production. Evidence continues to mount that the U.S. natural gas industry releases large amounts of methane, and in 2021, global methane emissions increased by a record amount.

The world is facing a methane emergency, and a growing consensus says reducing methane emissions is the most effective way to slow global warming in the near term. Any efforts to produce and use more methane, either by creating blue hydrogen or by mixing green hydrogen with methane, would send the world in the wrong direction.

Green Hydrogen’s Emergence Is Great News

Fortunately for those hoping to maintain a livable climate, green hydrogen is now cost-competitive and could make efforts to reduce carbon dioxide emissions much more successful. If green hydrogen were used only to replace existing global hydrogen production (2 percent of emissions) and the coal used in the steel industry (8 percent), it could eliminate 10 percent of global carbon dioxide emissions. Recharge reports that the green hydrogen production tax credit in the Inflation Reduction Act would allow the steel industry to make green steel that is cost competitive with current, very dirty, steel.

However, that good news for the climate is under threat. The network of interests with links to the natural gas industry DeSmog has mapped in the United States seems set on convincing policymakers that blue hydrogen is clean and that power producers should mix green hydrogen with methane. Either outcome would endanger the chances of preserving a livable climate.

“We plan to build a blue hydrogen plant at our integrated refining and petrochemical facility in Baytown, Texas,” a spokesperson for ExxonMobil told DeSmog, calling it “an example of a project that works today, subject to supportive government policy.” That government policy refers to U.S. taxpayer dollars from the Inflation Reduction Act, though hydrogen companies are calling these incentives a “game changer” for green hydrogen investments.

This is the world’s first steel made without burning fossil fuels. Steel is a main emitter so this is hugely important!

— Mike Hudema (@MikeHudema) August 9, 2022

We have so many solutions to solve the #climatecrisis. Implement them. #ActOnClimate#ClimateAction #reneables #renewableenergy #GreenNewDeal pic.twitter.com/0C2GO6OO9d

And despite efforts by fossil fuel interests to push blue hydrogen in Canada, Germany just signed a “hydrogen alliance” deal with the Canadian government to import green hydrogen from the North American nation. Germany isn’t saying it won’t use blue hydrogen but has said it won’t put government money into those projects. (The difficulties of shipping hydrogen will limit the success of this alliance, and as DeSmog has reported previously, the Canada-Germany energy partnership seems geared mostly towards enabling LNG exports from Canada to Germany, a priority which German leader Olaf Scholz echoed last week. “As Germany is moving away from Russian energy at warp speed, Canada is our partner of choice. For now, this means increasing our LNG imports. We hope that Canadian LNG will play a major role in this.”)

Time will tell whether recent developments send a signal to other countries to stop investing public money into blue hydrogen. In the meantime, expect to see continued lobbying from fossil fuel interests to keep the blue hydrogen window open for as long as possible.

CORRECTION 10/19/22: The article originally stated that Air Liquide was planning to build a blue hydrogen facility in Louisiana. We regret the error.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts