After months of protracted and often bitter wrangling, Ireland’s coalition government yesterday published emissions budgets for each part of the economy, in a bid to meet its ambitious climate goals.

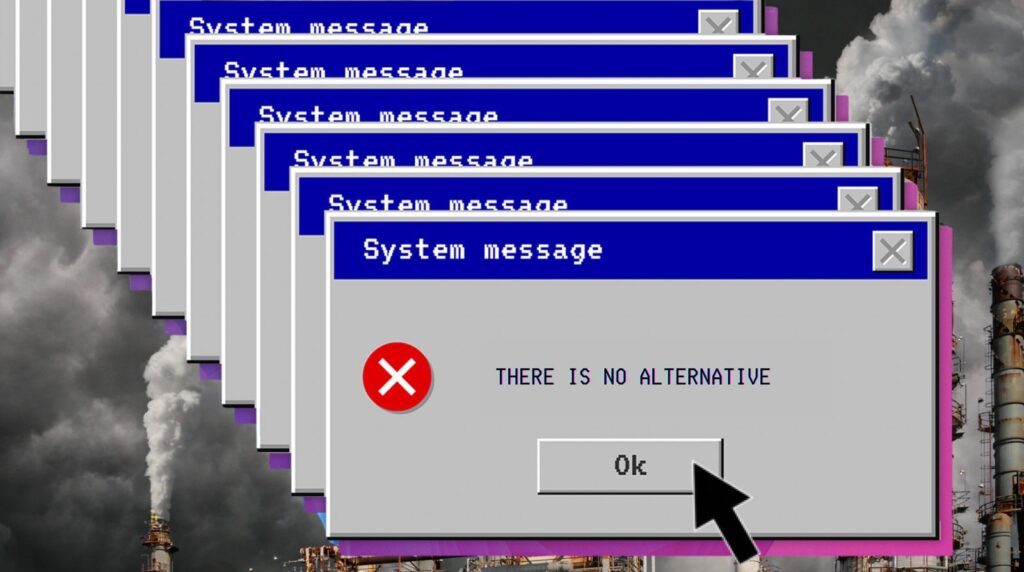

They take us a step further to achieving the 51 percent emissions cut by 2030 enshrined in legislation, but leave much to be desired. For a start, when all the sectoral targets are tallied up, they represent – at best – a 43 per cent reduction, according to the government’s own Climate Change Advisory Council (CCAC).

Its chair, Marie Donnelly, last night expressed concern at the “problematic” sectoral targets, which she described as “not consistent” with the objectives of Ireland’s climate laws.

By far the most politically contentious aspect of the new emissions budgets involves Ireland’s livestock-dominated agriculture sector, which currently accounts for 37.5 per cent of total national emissions, despite the sector contributing only around one percent to GDP.

Despite its relatively small size, the agriculture sector enjoys outsized political influence and protection in Ireland, partly due to its ability to apply pressure on rural members of parliament (TDs).

While originally given a budget range of 22-30 per cent, agriculture has been allocated a 25 per cent emissions cut target, well below sectors like energy and transport, and there are concerns this may make the government’s 2030 objectives all but impossible to achieve.

Irish Agriculture

Since the EU-wide lifting of milk quotas in 2015, Ireland’s dairy sector has expanded rapidly, adding around half a million cows. After the painful financial crash of 2008/9, the political atmosphere in Ireland ahead of the lifting of quotas was febrile. At the time, agriculture minister Simon Coveney hailed the decision, describing it as “the most important and exciting development for rural Ireland that we’ve seen in a generation”.

An analyst with Rabobank described the atmosphere in the dairy sector at the time as being “like the night before Christmas”. As a result of this rapid expansion, overall emissions from Ireland’s agricultural sector, which had been declining slowly up until around 2010, rose by a massive 19.3 per cent in the decade to 2021, with a corresponding rise in water pollution and declines in air quality caused by an increase in nitrogen fertiliser use.

Despite heavy investment in a marketing campaign called “Origin Green” to brand Irish produce as environmentally friendly, the director of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), Laura Burke, admitted in 2020 that its green reputation was “not supported by the evidence”.

The economic growth in the dairy sector, Burke added, “is happening at the expense of the environment as witnessed by the trends in water quality, emissions and biodiversity all going in the wrong direction.”

Climate Budget Fight

Despite all three government parties agreeing to the 51 per cent emissions cut by 2030, only the Green Party, with the smallest number of TDs, has attempted to hold the line in the face of a concerted PR and lobbying bid by the livestock sector to undermine Ireland’s climate ambition.

A number of backbench TDs from Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael, the centre-right coalition partners, have taken strong public positions against any restrictions on agriculture, with the Irish Farmers Association (IFA), a powerful lobby group leading the opposition.

The IFA has worked closely with controversial California-based air quality scientist, Frank Mitloehner, to argue against the need to sharply curtail methane emissions from livestock.

Last week, Mitloehner gave evidence to a parliamentary agriculture committee, during which he claimed that California had managed to reduce its livestock methane emissions in recent years by some 30 per cent due to the use of technology such as anaerobic digesters.

This claim was widely repeated by Irish politicians and agri lobbyists, but has since been refuted. According to the California Air Resources Board, livestock emissions in 2019 “are 18 per cent higher than 2000 levels”.

Steep Cuts for Other Sectors

While agriculture has come out with the lowest targets, Ireland’s electricity sector has been handed the hugely challenging objective of a 75 per cent carbon reduction by 2030.

Given the increasing demand on electricity from data centres, and the uptake of heat pumps and electric vehicles, hitting this target will take a herculean effort.

In addition to an expansion in offshore wind, solar energy, which is still in its infancy in Ireland, is also set for major growth, with some 6,000 hectares to be allocated for solar farm development.

That bodes well for some farmers who will be able to diversify their income away from livestock by leasing out parcels of land for solar farms.

That the government is also planning to support the rapid development of a biomethane sector, which it hopes will generate significant amounts of electricity annually by 2030, is less good news.

This is to be fuelled by a combination of slurry, food waste and grass, thereby allowing livestock farmers to reduce the density of their herds. But this looks like another flawed climate solution, with research warning that methane leakage from these “anaerobic digesters” could make them at least as bad as fossil fuels from an emissions perspective.

Meanwhile, Ireland’s transport sector has been ordered to cut its climate footprint in half by 2030, which may prove to be at least as difficult as agriculture. Rural Ireland is sparsely populated and car-dependent, with very limited public transport and cycling infrastructure, so decarbonising the country’s transport system in the next decade remains a major challenge.

With the third highest per capita emissions in the EU, largely as a result of its oversized ruminant livestock sector, it’s clear that Ireland has a long and winding road ahead towards climate neutrality.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts