When it comes to online disinformation, does it make sense to fight fire with fire using paid social media ads?

A new report by Reality Team, a nonprofit digital marketing group, suggests that social media ads can help reach people who aren’t closely watching topics like climate change or vaccine science and are often targeted by disinformation campaigns.

Surrounded by an endless array of questionable information online, lots of people aren’t quite sure what to think or how to sort truth from falsehoods. “They feel like there’s a lifetime of this stream of information that they haven’t caught up with,” Reality Team’s Debra Lavoy told DeSmog. “I can’t cope with the news, I know people are out there lying to me, so — I’m out.”

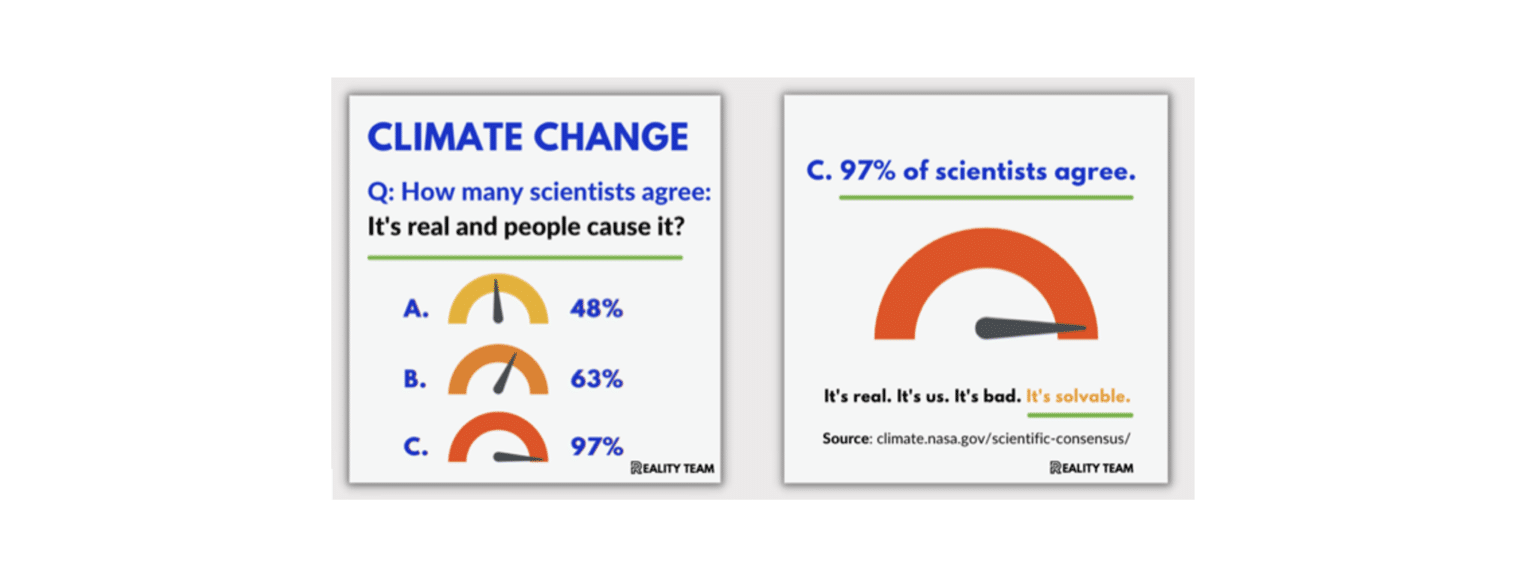

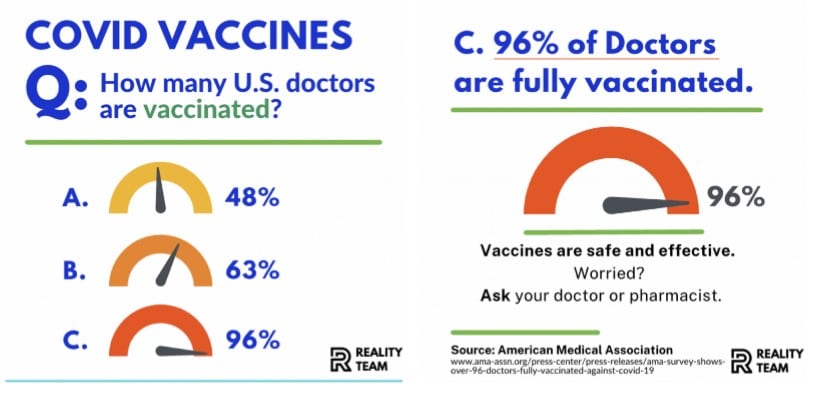

Reality Team ran Instagram ads aiming to put easy-to-digest information about climate change and vaccines in front of those viewers as they scrolled through social media feeds and ads. The group aimed to build people’s confidence in facts, arm them against disinformation campaigns, and help them sort what’s real from what isn’t.

The new report’s early findings seem promising, experts said, though they emphasized the importance of accountability for social media platforms and that more research could help show to what degree Reality Team’s results can be replicated and whether their work produces long-lasting change.

Reaching the ‘Super Online’

From the jump, Reality Team took a pragmatic path. Responding to disinformation “needed an approach that could be put into play quickly,” the new report says. “It had to be effective and couldn’t depend on help from the platforms, exotic technology, celebrity, or large sums of cash.”

“We knew this approach was unlikely to de-radicalize those already lost to delusional or extreme ideologies,” Reality Team wrote. “So we focused on the group we thought was both vulnerable and reachable.”

They relied on social media’s algorithms to help them find those people, folks who are already more likely to stumble on political issues in memes, social media feeds, and TikTok videos than anywhere else.

“It’s people who are super online but don’t read news,” said Lavoy, adding that depending how you measure, that can be about 20 percent of adults — and up to 80 percent of Instagram users under 35. “They casually run into news but they don’t seek it out.”

More than 1 in 20 viewers clicked on Reality Team’s Instagram ads, according to the report, giving the campaign a cost-per-click of 18 cents.

“At the outset it wasn’t our intent to focus on paid ads but we quickly realized that we got incredible levels of engagement on our paid ads at very cost-effective rates,” Lavoy said, adding that it cost about $8 to reach 1,000 viewers. “When I actually was in the marketing world, I would have killed for those sorts of stats.”

The group used existing scientific work to develop its messages, Lavoy said, using input from climate communications experts to figure out where people seemed most confused or vulnerable to disinformation and how to respond.

Disinformation and misinformation both, by definition, use false claims. (Disinformation involves deliberately spreading falsehoods, while misinformation isn’t defined by the speaker’s intent so it can be accidental or on purpose). Lavoy said they approached the tricky task of distinguishing disinformation from sound fact in part by focusing on areas where key information is well established and in part, by consulting directly with experts in each field. Their ads also cite their sources, so viewers can judge for themselves.

Reality Team also had to figure out how to answer some hard questions in plain language. “Things like, we’ve heard that the cost of clean energy’s going down — how much has it gone down?” Levoy said. “It took us a week to decode that data.”

It then tested to see whether the ads affected the way people thought about issues by showing a 10-second video ad to a group of about 200 people and comparing them to another equally-sized control group that didn’t watch the video. “The video watchers answered correctly at a significantly higher rate than the control group,” the report says, adding that they also found a 17 percent increase in support for “government investment in climate solutions” after people watched their videos.

Putting up a Fight

Independent experts said the report overall seemed reasonable but noted that it wasn’t the result of peer-reviewed study, making it harder to gauge results independently. And open questions remain.

“At face value, this seems like a stimulus-recall test,” said Hywell Williams, a data science professor at the University of Exeter in the U.K., looking at the video and poll tests used by Reality Team. “I show you something, then ask you if you can remember it. Lasting effects or changes in deeper beliefs are not known from this study.”

“So it is hard to judge the real impact,” Williams added.

“This is the most promising approach I’ve seen,” said Michael Khoo, co-chair of the Climate Disinformation Coalition at Friends of the Earth. “More broadly, social media companies like Facebook and Twitter need to be held accountable for enabling the spread of so much disinformation on climate and many other issues,” Khoo added.

“The disinformation ecosystem is highly cooperative and coordinated and their goal isn’t to convince someone of something, their goal is to flood the zone with garbage.”

– Debra Lavoy

Lavoy emphasized that Reality Team’s ads were built to be just one tool in an anti-disinformation toolbox.

The Center for Countering Digital Hate, for example, focuses on 12 people, dubbed “The Disinformation Dozen,” whose work is behind roughly two-thirds of anti-vaccine misinformation on social media, Lavoy noted. “There’s similar stuff for climate, they call them the ‘toxic ten’ pushers of climate disinformation. And the platforms absolutely tolerate this,” Levoy said. “But while we wait for the platforms to take responsibility, for regulators to force them to take responsibility, for technology to help them and/or others solve the problem, we are trying to engage in sort of hand-to-hand combat.”

That’s despite the fact that the odds, in many ways, are stacked in favor of disinformation, which can be sensationalistic and isn’t tethered to provable facts — which helps explain why it doesn’t take a lot of it to make big waves.

“The disinformation ecosystem is highly cooperative and coordinated and their goal isn’t to convince someone of something, their goal is to flood the zone with garbage,” Levoy said. “Last year, we sort of followed where the disinformation was. This year, we are trying to predict where the disinformation will be by looking at where competitive elections are and we’re going to focus on climate, vaccines, election integrity, and something we call dirty disinfo tricks.”

“We can compete with them,” Levoy said. “At the very least we can put up a fight.”

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts