“It is like it’s an environmental war zone,” Traditional Chief Shirell Parfait-Dardar of the Grand Caillou/Dulac Band of Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw Tribe, told me outside her new home in Chauvin, Louisiana, about 70 miles southwest of New Orleans.

On August 29, Hurricane Ida destroyed the dream home she and her husband had almost finished building. The stormed slammed into Louisiana with maximum sustained winds of 150 mph, just shy of a Category 5 hurricane.

When she drives to and from her new property, destroyed and damaged structures are still plentiful in the vast area impacted by the storm and she often passes the remains of her demolished former home a few miles away. It is now part of a large pile of debris in a temporary landfill.

Seeing it saddens her since the home and her family’s belongings had sentimental value, but she considers herself lucky: Her family was able to purchase a damaged but repairable home next door to the one they lost from neighbors who weren’t up for returning after Hurricane Ida. With so many structures destroyed, few housing options exist other than rebuilding from scratch — and Parfait-Dardar didn’t have the money to do that.

Being able to remain where her tribe’s members can find her makes it easier for her to help them navigate the recovery process. It has been slow going, not just for her tribe but for many of those who have returned to the areas hardest hit by Ida throughout southern Louisiana.

Parfait-Dardar estimates that about 75 percent of her community is back, which she credits to the tribe’s resiliency. But with the next Atlantic storm season less than three months away, her community is more vulnerable than ever.

The pandemic, material shortages, the expense of rebuilding more resilient structures, inflation, and insufficient funding are exasperating the challenges of recovery. But perhaps the biggest barrier to building back better is the lack of equitable and coordinated approaches to recovering from disaster and halting climate change.

“Day to day life is more difficult after a disaster,” Parfait-Dardar told me. I heard this sentiment echoed by many over the past couple weeks while I revisited some of the areas hardest hit by Hurricane Ida six months after the storm for DeSmog.

When I visited Parfait-Dardar on March 4, she had just returned from a furniture store discouraged and empty handed. She couldn’t find a couch for less than $2,000 dollars and doesn’t want to get expensive things for her new house since she knows there is a chance she could lose everything again. She told me that getting anyone to give a price quote, let alone do repair work, is another major challenge.

Many of those reliant on FEMA are surprised to learn the agency’s role isn’t to help them get back what they lost. The maximum amount available through FEMA is $36,000, covering both damage to the home and its contents. This falls far short of what most people need to repair, let alone rebuild, structures that were damaged but not completely destroyed.

“FEMA is looking at what it would take to make the dwelling habitable not what it would take to bring it back to pre-disaster condition. That is the role of insurance,” Robert Howard, an assistant external affairs officer for FEMA, told me by email.

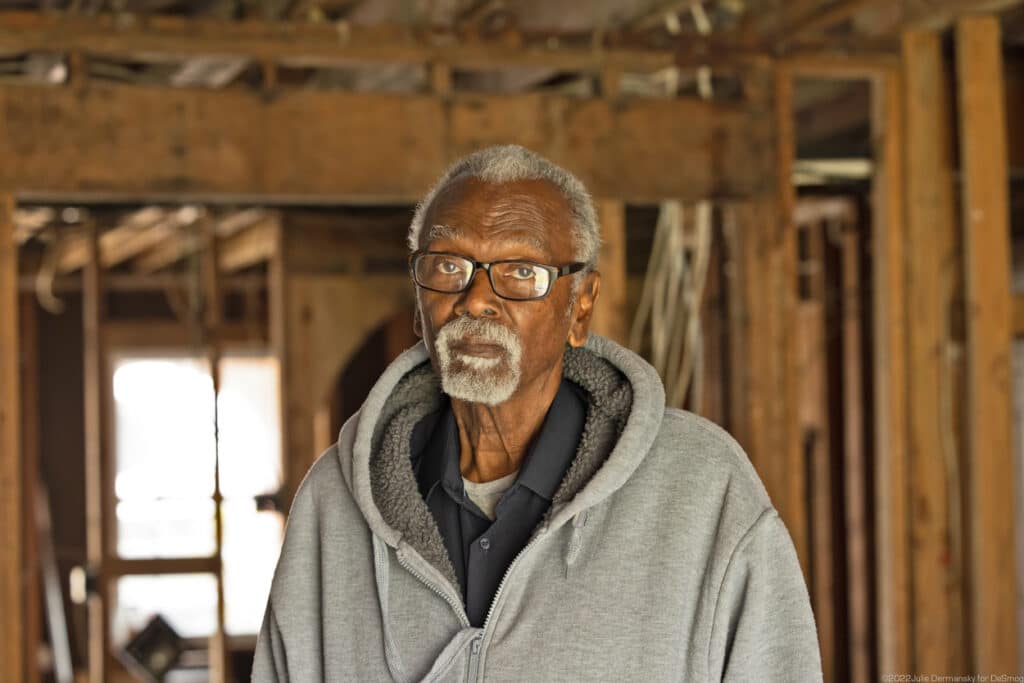

But many people lack insurance. On February 27, I returned to Reserve, Louisiana, in the heart of “Cancer Alley,” another region badly impacted by Ida. There, I met with Robert Taylor, the founder of Concerned Citizens of St. John, a community group that has been fighting for clean air since 2016.

Taylor, who is in his 80s, had let his insurance lapse before the storm hit and is one of many reliant on whatever funds FEMA will provide in order to recover from the storm. And even if he is allowed the maximum funds FEMA can provide to him, $36,000, it is far less than he needs to make his home habitable again. Ida tore the roof off Taylor’s house and soaked all of his belongings, and he told me that to entirely rebuild the roof will cost more than $30,000 but FEMA offered him just $18,000. He appealed FEMA’s determination more than 60 days ago and hasn’t heard back, although FEMA told him it could take 90 days before a new determination is made.

While Taylor is grateful for any help he can get, he is frustrated by how FEMA is distributing resources. Some in his community who lost less than he did received the full $36,000 and a temporary manufactured home (known as a FEMA trailer), but he was only provided with a camper trailer that isn’t big enough for him, his son, and his teenage granddaughter. He has been staying with his daughter in New Orleans about 30 miles away, and driving back and forth is making the recovery process even more daunting as the cost of gas continues to rise.

He is in talks with different non-profits that help storm victims recover. But he knows that even if he finds a way to rebuild his house the growing risk of extreme weather will keep insurance rates high. Despite all this — and the fact that his home is a couple miles north of the Denka Performance Elastomer plant, which makes the synthetic rubber commonly called Neoprene and is notorious for its toxic emissions — rebuilding in the same spot is a given for him. It is where his community is and where he feels most at home.

The challenges facing storm victims in Ida’s aftermath are not new to southern Louisiana. But Taylor believes that recovery from Ida is proving to be more difficult than ever for his community due to financial hits from the pandemic and health issues made worse by the toxic emissions his community continues to be “bombarded with.” That, coupled with a shortage of everything from basic services to building materials, makes him worried that many won’t be able to fully get back on their feet.

Later that day, I also returned to Ironton, Louisiana, home to a small Black community, 30 miles south of New Orleans, that was hit with a 12-foot storm surge from Ida. The floodwaters dislodged tombs and coffins, dispersing them around the town along with cars, sheds, and entire homes. The tombs and coffins are back in the historic cemetery, but the cemetery itself is still in a state of disrepair. Only about 10 percent of the residents have returned so far, according to the community members I spoke to, but they expect others to come back to Ironton when they are able.

On February 15, during a visit to the Pointe-au-Chien Tribe, I met Shirley Verdin who lives across the bayou from the tribal center. She is another of the many people who were uninsured when Hurricane Ida hit, and are now dependent on FEMA funding.

Verdin had carried homeowners insurance for many years, but couldn’t get coverage; many insurance companies no longer offer policies to coastal communities due to the increased risk driven by climate change. The only insurance Verdin could have carried was for the contents of her home, but due to its high cost, she went without it.

She told me that FEMA has offered her $4,000, despite her home being totaled and all of her belongings destroyed. Her daughter helped file an appeal for her but, like most, even if she gets the maximum funding available through FEMA, it will not be enough to rebuild.

FEMA provided her with a trailer in late December. But more than two months later, she still had not been able to get power hooked up to it, another problem frustrating many returning to the area. Nevertheless, Verdin does not want to think about moving.

“I love being by the water and my family,” Verdin told me while sitting on the wooden steps that are all that remains of her home, which sat on a raised platform. “We have always had what we needed — we live off the water — with the seafood. After being in the same home for over 60 years, I can’t image living anywhere else.”

Despite the mounting challenges facing those who were impacted by Ida throughout southern Louisiana, most want to stay in the area even without a path to start rebuilding. “No one wants to abandon their home,” Parfait-Dardar said. “Everything they know and love is here.”

“Those addressing the climate crisis by focusing on managed retreat aren’t listening to coastal communities,” she continued. “We don’t want managed retreat. If we could safely stay where we are, we don’t want to leave.”

While Parfait-Dardar acknowledged some coastal communities already have no choice but to relocate, like the community on Isle de Jean Charles, which is facing some of the fastest land erosion along the Gulf Coast. But for any coastal community’s relocation to work, the community “has to be front and center of the decision making, of the planning because it’s for them,” Parfait-Dardar said. “Who better to know what they need than themselves.”

One obstacle Parfait-Dardar’s tribe has faced in recovering from Ida and responding to climate change generally is that it is recognized by the state but not the federal government, so it can’t access certain federal assistance.

Theresa Dardar is a member of the Pointe-au-Chien Indian Tribe, another one that is recognized only by the state. I met her on February 15 at the Tribe’s center in Point-aux-Chenes, 16 miles southeast of Chauvin. The situation for her tribe also remains dire.

After the storm, a flurry of volunteers helped the community tear down totaled structures and clear debris, but little progress has been made since, Dardar told me. Many have returned and are living in campers provided by the state or in FEMA trailers, but the community still lacks the funding it needs to help everyone rebuild.

Her tribe and five others in southern Louisiana, including Parfait-Dardar’s, are part of the First Peoples’ Conservation Council of Louisiana. They are continuing their fight to get federal recognition, which would give them access to more resources. In the meantime, she fears that people have forgotten how badly her community was impacted by Ida and hopes that by talking to journalists like me, that people will realize that they still need help.

The road to recovery is still long for people affected by Ida all over southern Louisiana, and is being made increasingly complicated by inflation, materials and labor shortages, and ongoing pollution. But Parfait-Dardar is already thinking beyond rebuilding. Her long-term goal is halting climate change so that her tribe and others can remain in place.

“There are inexpensive ways in-sync with our environment to heal the damage that would still allow us to stay in place for even longer,” Parfait-Dardar added. “Things that can be done now, including backfilling canals and creating living shorelines. And guess what? That gives us more time for young minds to keep thinking of innovative ways to build back better instead of retreating.”

She believes that “if we radically cut carbon emissions and build back better, most communities can continue to live in south Louisiana.” And she asserts that solutions for both are already at hand, although they would require radical changes.

Instead of FEMA’s current model of temporary housing and direct funds, which falls far short of enabling people to rebuild in a resilient way, she would like to see the agency use the same amount of money but follow the model the Mennonite Disaster Services uses: They come into disaster zones and build or restore homes with materials suitable to withstand extreme weather conditions. They charge only for the materials, and these far more resilient homes cost less than a FEMA trailer.

And her time spent on the Governor’s Climate Initiatives Task Force affirmed her belief that the mechanisms to transition to renewable energy and cut emissions are already at hand, though she questions whether we will utilize them.

Optimism about our ability to halt climate change’s worst impacts is echoed by a recent piece in the Washington Post, co-authored by renowned climate scientist Michael Mann, Mark Hertsgaard, the executive director of Covering Climate Now, and Saleemul Huq, the director of the International Centre on Climate Change and Development.

It brought to light some positive news tucked inside the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s August 2021 report: Climate scientists now believe that global temperatures could fall as quickly as three to five years after drastic emissions cuts.

The latest IPCC report, released on February 27, reiterates those findings but warns that if we delay taking action, the catastrophic impacts of climate change would make our world unrecognizable.

That reality worries Parfait-Dardar. “Disasters are exacerbated by what humanity is doing, by not being in alignment with our planet’s natural process,” she said. “We are causing great harm to our planet and she’s reacting. So long as we do not change our ways, you are going to continue to see these things happen.”

Previous IPCC reports have warned that Indigenous communities are going to be hit harder by climate change, and Parfait-Dardar believes they already are. She continues to fight for climate justice because she knows that “if we don’t start implementing the things that we know can work right now, entire communities will be destroyed.”

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts