The U.S. Chamber of Commerce, an ultra-powerful business lobby, does not disclose its members, but it represents the interests of America’s largest corporations — some of which have a long record of breaking state and federal laws.

A new report from consumer watchdog group Public Citizen details how 111 known members of the Chamber — including major polluters and banks that back fossil fuels — have violated state and federal laws at least 15,896 times since 2000, totaling more than $156 billion in fines and penalties.

These findings come after the Chamber attacked the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) late last year for the agency’s efforts to step up enforcement of unlawful corporate behavior, calling increased oversight a “war on American businesses.”

“In fact, it is the Chamber’s ranks that are packed with rogues,” Rick Claypool, a Public Citizen research director and author of the report, said in a statement. “The time is long overdue for big corporations that engage in abusive, monopolistic, and predatory behaviors to face serious consequences. Corporate crime shouldn’t pay, and honest businesses should welcome the FTC’s recent pledge to crack down on corporate crime.”

Of the 111 known members, JPMorgan Chase has paid the most penalties, racking up more than $35 billion over the past two decades, according to Public Citizen. Other banks also topped the list, including Citigroup and Wells Fargo.

The oil, gas, and coal industries, including Occidental Petroleum, Duke Energy, Marathon Petroleum, and Chevron, are also prominent members of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce and have been frequent violators of state and federal laws.

Occidental Petroleum was fined the most out of any energy company, hit with penalties an estimated 235 times. The bulk of the fines came from a massive $5.15 billion settlement between a subsidiary and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency over the company’s attempts to evade its environmental cleanup liabilities by shifting troubled assets to a shell company.

Another notable example is Duke Energy, which has paid more than $2.8 billion in penalties since 2000, much of which are related to the massive 2014 coal ash spill in North Carolina.

The nature of the violations varies. For instance, Chevron has paid more than $975 million in penalties since 2000 (Violation Tracker data pegs it at $1.07 billion), with violations ranging from wrongful termination of employees to a $30 million settlement over a kickback scheme related to Iraq’s oil-for-food program in 2001 and 2002. The oil giant has also accumulated a long list of environmental violations that often result in small civil penalties accompanied by commitments to spend much more on upgrading equipment.

Range Resources, a Texas-based fracking company with a heavy drilling presence in Pennsylvania, has accumulated more than $16 million in penalties since 2000. That included pleading no contest in 2020 to a criminal investigation brought by the Pennsylvania Attorney General related to an incident in which the company covered up leaks from fracking waste storage ponds.

In total, the Chamber of Commerce’s oil and gas members have logged more than 1,600 violations totaling $8.9 billion in penalties, the report said.

“It’s a lot of lawbreaking. On the other hand, it can also be seen as the tip of the iceberg,” Claypool told DeSmog, referring to the all the violations committed by the Chamber of Commerce’s members.

He noted that the data he used from Violation Tracker, a database on corporate misconduct, only captures violations involving monetary penalties in excess of $5,000. It doesn’t account for non-monetary enforcement actions taken by regulators, and likely misses a lot of other corporate wrongdoing. “Just the way corporate enforcement has been going, it’s sort of only the most egregious cases that are brought,” he said.

The findings are “jaw-dropping even for people like me who study, teach, and write about corporate criminal misconduct for a living,” Jennifer Taub, a professor at Western New England University School of Law and author of Big Dirty Money, a book on corporate profiteering and white-collar crime, wrote to DeSmog in an email. “Given their membership’s history of repeat offending, it takes a lot of nerve for the Chamber of Commerce to push back against the Federal Trade Commission when it’s just doing its job by referring suspected criminal conduct to the Department of Justice.”

‘Cost of Doing Business’

The Biden administration took several actions in 2021 that signaled an intention to take a slightly firmer stand on corporate misconduct. In October, the Department of Justice issued a memorandum that directs prosecutors to take into account a company’s past history of violations, including from different states or countries, and from all of its subsidiaries. That was a departure from the past, when prosecutors looked more narrowly at only the violation in question.

In addition, President Biden appointed new regulators that have a reputation for strong corporate oversight, including the new chair of the FTC, Lina M. Khan. Ostensibly responsible for protecting consumers from anticompetitive and deceptive behavior, the FTC has largely taken a hands-off approach for the past few decades. But that is changing. Legal scholars and antitrust activists have spent several years calling for more assertive oversight, and they have had the ear of the White House during the Biden era.

Khan has sought to reinvigorate the FTC, and in November, the commission said that it would expand its criminal referral program, a more concerted effort to push local, state, federal, and international law enforcement to prosecute civil violations and crimes committed by businesses. The FTC acknowledged that small financial penalties offer very little in the way of a deterrent for lawbreakers.

“At a time when major corporate lawbreakers can treat civil fines as a cost of doing business, government authorities must ensure that criminal conduct is followed by criminal punishment,” Khan said in a statement in November. “Today the FTC is redoubling its commitment and improving its processes to expeditiously refer criminal behavior to criminal authorities, promoting accountability and deterrence.”

The FTC is waging war on American business. We are ready and fighting back. We will use every tool at our disposal to challenge the agency’s blatant power grabs and unlawful actions targeting America’s employers. https://t.co/M6Q8BYWcc8

— Suzanne Clark (@SuzanneUSCC) November 19, 2021

The U.S. Chamber of Commerce erupted in anger at the move. “The FTC is waging a war against American businesses, so the U.S. Chamber is fighting back to protect free enterprise, American competitiveness, and economic growth,” Suzanne P. Clark, president and CEO of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, said in a statement. Clark said the FTC’s intention to expand its criminal referral program is a “radical departure from its core mission.”

“Today, the Chamber is putting the FTC on notice that we will use every tool at our disposal, including litigation, to stop its abuse of power,” Clark said.

The Chamber’s Aggressive Turn

One of the largest and most powerful business lobbying groups, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce represents corporate titans in Washington D.C., often watering down or blocking regulations on everything from air pollution to labor protections and antitrust enforcement. The Chamber has also fought climate legislation for years, and counts some of the nation’s largest polluters among its members. The lobbying outfit has spent millions of dollars fighting the Build Back Better Act over the last few months, objecting to higher taxes on corporations and also to provisions included in the legislation that would beef up FTC authority over illegal corporate behavior.

This aggressive assault not only on efforts to tax and regulate business, but also on basic government oversight of criminal behavior, has a long lineage. The origin of U.S. Chamber of Commerce’s influence and political machinery dates back decades.

As World War II was winding down, American businesses strategized how to protect their interests and beat back government involvement in the economy. According to documents curated by Amy Westervelt at Rigged, an influential memo from the mid-1940s advising corporate America to sell the concept of “free enterprise” set the tone for the post-war era.

“There is grave danger that many millions of Americans will be given the impression that the free enterprise system is full of gross abuses and dishonesties,” Earl Newsom, a public relations consultant who advised some of the most powerful corporations in the country, including Ford, GM, and Standard Oil of New Jersey, wrote in the memo. “The immediate future is vital, because during the period between now and the end of the war the public’s mind will be made up one way or the other.”

The one I've been thinking about the most lately is this strategy from Earl Newsom, PR advisor to Standard Oil of New Jersey from the late 1920s to the late 1960s. This was in a folder marked "confidential" and is a strategy drafted in 1944, the year WWII ended pic.twitter.com/nGxwmqpQsi

— Amy Westervelt (@amywestervelt) October 29, 2021

He advised companies to engage in advertising campaigns to influence public perception in favor of big business. However, he cautioned that trade groups such as the National Association of Manufacturers and the U.S. Chamber of Commerce should not be used to lead these campaigns, nor should businesses set up newly created front groups, as the effort would look too coordinated and overt. Instead, he encouraged companies to wage their own advertising efforts independently of each other.

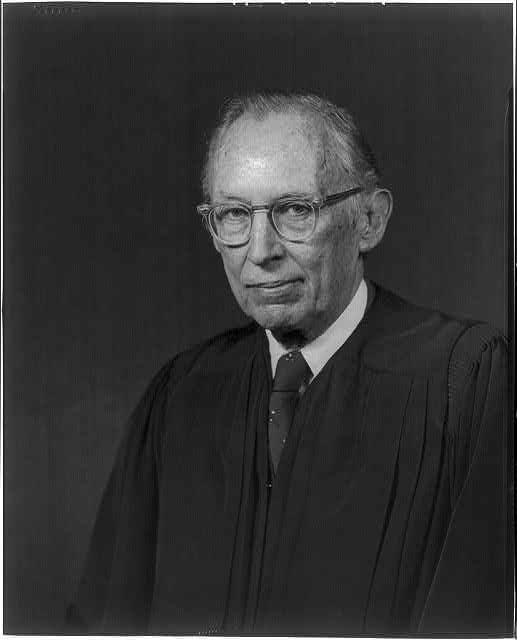

That strategy moved in a decisively more aggressive direction in the 1970s. One of the pivotal moments came in 1971 when Lewis Powell, a corporate lawyer and a board member of tobacco giant Phillip Morris, wrote a confidential memo for the U.S. Chamber of Commerce. Powell was later nominated to the U.S. Supreme Court by President Richard Nixon, where he served until 1987.

In the wake of new environmental and consumer protection laws, Powell warned that the “American economic system is under broad attack.” The assault was not only coming from “Communists, New Leftists and other revolutionaries,” but more disturbingly for Powell, criticism of American business was also coming from “perfectly respectable elements of society,” including “college campus, the pulpit, the media, the intellectual and literary journals, the arts and sciences, and from politicians.”

Powell warned that “business and the enterprise system are in deep trouble, and the hour is late.” He called on American businesses to transform themselves into a more aggressive political force.

In a departure from Newsom’s advice three decades prior, Powell said that independent action from companies was not enough. Strength would only come from a coordinated and well-funded effort to shape public perception around the role of corporate America in the economy. “The role of the National Chamber of Commerce is therefore vital,” he wrote.

Powell said that the media should be kept “under constant surveillance.” When criticisms of the free enterprise system appear in the media, businesses should file complaints with the Federal Communications Commission. Critiques of corporate America should be countered on television, radio, scholarly journals, books, on college campuses, in the courts — basically anywhere and everywhere.

“It certainly didn’t start aggressively,” Charlie Cray, a senior researcher at Greenpeace USA, told DeSmog, referring to the Chamber’s early days. “That was the whole point of the memo. It was like, ‘look, you’re getting your asses whooped by the left.’”

Cray has argued that the Powell memo “helped catalyze a new business activist movement” beginning in the early 1970s that continues through today.

The extent of the influence of the Powell memo is up for debate, but, in hindsight, it describes the trajectory that the business world pursued. The Chamber of Commerce is now arguably the most powerful lobbying force in Washington.

The Chamber’s current assault on the FTC is an extension of this decades-long effort to weaken government oversight. Current CEO Suzanne P. Clark’s language of a “war against American businesses” sounds nearly identical to Powell’s warning that the American enterprise system was “under broad attack.”

Over the last few decades, several overarching issues have defined the Chamber’s priorities, Cray said. One is tort reform, a campaign to reduce the punitive damages paid by corporations for wrongdoing, and more broadly to weaken the ability of consumers to bring cases against businesses. Another more obvious priority for the Chamber has been to lower taxes.

At the same time, as the Public Citizen report shows, lawbreaking by the Chamber’s members is rife. “The Chamber represents the biggest of big businesses, and it’s the biggest of big businesses that enjoy a tremendous amount of leniency from federal enforcement authorities,” Claypool said.

The Chamber did not respond to a request for comment.

Taub has calculated that white-collar crime likely costs the American economy between $300 and $800 billion per year, while street crimes like burglary and theft cost around $16 billion.

“This sentiment that, ‘oh, pity the poor corporation who is violating the law’…that message needs to be taken with such a heap of salt,” Claypool said. “Maybe the reason the Chamber is opposing enforcement is because it represents companies that have violated the law and want to minimize the amount of enforcement.”

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts