By Ted Auch, PhD, FracTracker Alliance, with contributions from Shannon Smith of FracTracker Alliance

The fracked natural gas industry has never been the most responsible or efficient consumer of resources. Drillers are using ever-increasing amounts of water and sand in order to produce the same volume of gas, with a corresponding rise in the levels of solid and liquid waste created.

Nevertheless, the industry has begun a new wave of branding around “Responsibly Sourced Natural Gas,” or RSG. But what does RSG really mean?

We argue that right now it’s an inadequate and ill-defined measurement of the overall ecological and social burden imposed by fracking. Instead, we suggest a new ratio for more accurately calculating fracked gas’s full impacts so that the fossil fuel industry can’t use RSG standards as a thin green veil for continuing its polluting practices.

What Is RSG?

RSG is a new term used in the natural gas industry to describe voluntary reporting initiatives, centered largely around emissions of the powerful climate pollutant methane, but which may also include other criteria such as air quality, water stewardship, land impacts, and “community interests.” Think of RSG as attempting to create an oil and gas equivalent of fair-trade labels for clothing or green building standards for architecture.

RSG programs are intended in large part to boost investor confidence by way of “strategic storytelling,” as one industry consulting firm put it. Proponents of such voluntary standards are trying to simultaneously compete in the domestic and global energy market, increase profit margins, and attract environmental, social, and governance (ESG) investors, a hot trend in the investing world right now.

But the definition of “responsibly sourced” is inconsistent across the 20 such initiatives that are currently available. Only two of these require the use of third-party auditors to verify the operators’ reporting via independent on-site measurements. That’s unlike many other sectors, such as in organic agriculture.

However, even independent auditing isn’t a perfect solution. The company Project Canary offers one such RSG certification program called TrustWell Responsible Gas. Project Canary defines RSG as fracked gas that “has undergone an independent, third-party certification assessing sustainability through operational excellence and environmental stewardship across various categories, including air, water, land, and community.”

While this sounds promising, its methodology and data are not publicly available, making it difficult to assess their claims. And the company’s website is littered with language around using RSG certification as a tool that achieves “higher profit margins” and addresses climate concerns from the public, importing countries, and ESG investors.

Quantifying methane emissions is central to most of the RSG programs, but none of them require full public disclosure of the methane levels that are actually released. That practice mirrors the secretive nature of the fracked oil and gas industry, which also does not publicly disclose the full list of chemicals used during the fracking process.

The various “responsibly sourced” certification programs need more transparency, standardization, and punitive measures for companies that play fast and loose with the concepts and requirements underlying all manner of RSG schemes. The latter would involve significant monetary penalties or expulsion from RSG programs when a gas well fails to comply with the environmental standards. Those changes would go a long way toward defining what exactly constitutes RSG, how it is calculated, and whether it is a meaningful measure of environmental impacts.

There are benefits to the natural gas industry reducing methane emissions — most notably for the rapidly destabilizing climate — but it represents low-hanging fruit for the industry to clean up its practices. Given the scale of the climate crisis, we need a much more serious commitment on the part of policymakers and energy companies to phase out fracked oil and gas production entirely and in the interim to significantly lessen its resource demands and waste production.

After all, RSG programs do not transform natural gas from a fossil fuel that accelerates climate change into a renewable fuel that does not. Instead, the RSG label offers the oil and gas industry an undeserved pass to continue gobbling up resources and polluting the environment, at the expense of people and the climate.

Fracked Gas: Using More and More Water, Creating More and More Waste

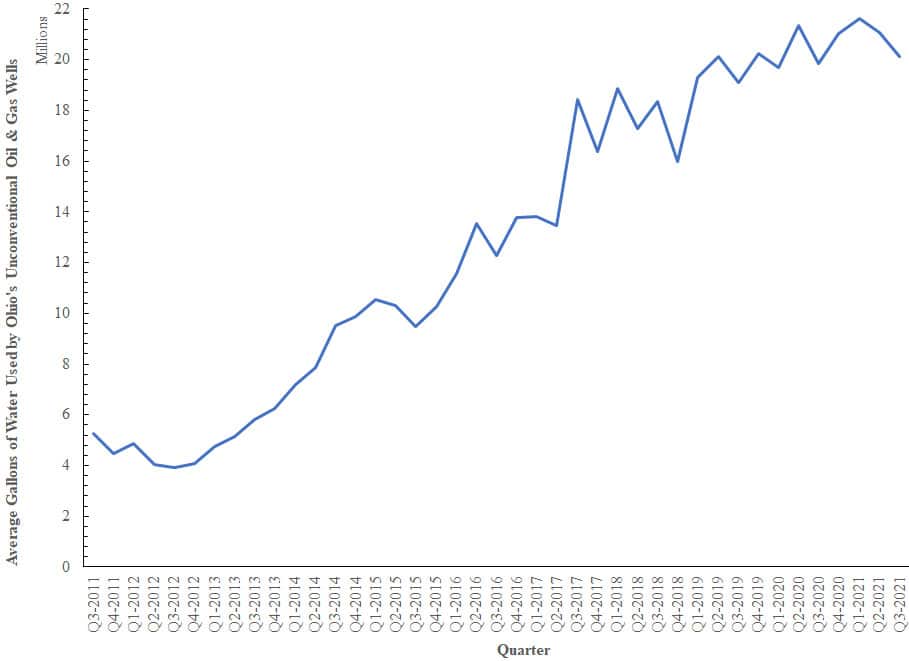

The average fracked gas well in the Marcellus and Utica Shale fields, which span states including Pennsylvania and Ohio, is now twice as long as those wells drilled just a decade ago, according to a FracTracker Alliance analysis. In addition, these fracked wells now use three times more water and sand, the latter of which is used to prop open cracks in the shale rock and allow the natural gas to escape to the surface. That means fracking an average gas well in Ohio went from using 6.3 million gallons of water in 2012 to 21 million gallons in 2021.

The average amount of water used per well by the unconventional oil and gas industry in Ohio from 2011 to 2021, demonstrating demand for surface freshwater is increasing by 6 to 38% per year. Credit: FracTracker Alliance, update to a periodic water supply and demand analysis for Ohio.

Furthermore, our research at FracTracker has found that the amount of liquid fracking waste being injected into oil and gas waste disposal wells across states like Ohio has increased four to five-fold during this same period.

It is no coincidence that this exponential increase in fracked gas resource demand comes as the industry is seeing natural gas production declines that render wells unprofitable within a couple of years rather than decades, as drillers widely touted in the past in states like Ohio and North Dakota.

Local government entities charged with determining the price of water and waste disposal methods throughout the Ohio River Valley have deemed water a surplus commodity and fracking waste a benign and necessary byproduct of the fracking boom. Their attitudes result in water and fracking waste being priced in a way that it doesn’t interfere with business as usual. This arrangement places the burden of environmental and social costs onto the public in the name of private profit.

For example, the private oil and gas firm Hilcorp Energy is in negotiations with the city of Salem, Ohio, “to purchase untreated water…for fracking over five years, at a price of $1.95 per 1,000 gallons.” That deal, if finalized, would make this the cheapest known source of water for fracking in the Marcellus and Utica basins.

Fracking waste is hazardous and often radioactive, meaning that water resources used to frack for natural gas are never fully recoverable. The industry can’t treat that water to make it safe to drink again.

Solid waste produced in the fracking process is often disposed of in municipal landfills where contaminated runoff can enter waterways. In addition, our understanding of the fracking waste volumes processed by any given landfill remains poor because of weak state and federal regulation.

The injection of waste into underground geologic formations across the Marcellus and Utica region has resulted in earthquake activity as well as several instances where the injected waste, instead of staying below ground, ends up returning to the surface through the maze of increasingly connected industry wells now fracturing the land.

Regions like the Ohio River Valley are being targeted for even more fracking waste injection wells, with proposals for pumping in larger daily volumes. That increase, however, would require greater pressures to keep the injected waste below ground. And these greater pressures will likely result in more instances in which liquid fracking waste spews out above ground, as witnessed by several residents of Dexter City, Ohio, this past February.

Oil and gas transportation and storage companies like Enlink Midstream and Guttman Realty Co. are proposing to transport fracking wastewater from gas fields to disposal wells by barge, which would make its disposal even cheaper. In addition, industry-friendly politicians are floating bills in statehouses that would commodify oil and gas waste, making it easier to repurpose and sell for other uses, such as spreading on snowy roads throughout the region as a salt substitute in the winter.

Fixing the Formula

If the natural gas industry is going to market itself as “responsible,” then any evaluation of the product’s environmental and social impacts should at least incorporate its biggest inputs — water and sand use — and biggest outputs — waste production — in addition to its methane emissions. Even this accounting doesn’t capture the full social and environmental damages of natural gas production, but it provides a fuller and more accurate assessment of a particular operator’s impacts for a given amount of gas produced.

We suggest two key changes to create a more complete and accurate standard for RSG programs that better represent the set of harms caused by producing fracked gas. First, keep methane as a measurement in an RSG ratio but add to it the sum of outputs like liquid and solid waste and non-renewable supplies like sand and water consumption. And incorporate the number of acres of land permanently altered by pipelines, pads, and related infrastructure. For such data to be useful, it must be standardized across initiatives, verified by an accredited third-party inspector, and ideally, disclosed to the public.

Secondly, voluntary RSG programs are not enough of an incentive for operators to reverse the trend of exponential resource use and waste production — these things need to come at a reasonable cost. The federal regulators in the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, U.S. Army Corp of Engineers, and the Department of the Interior should implement a national price floor and progressive pricing structure for the industry’s unquenchable thirst for freshwater and their similarly irresponsible and outsized production of liquid and solid waste.

In a variety of ways, fracking inevitably puts our health and environment at risk. It’s an incredibly precarious use of natural resources, and RSG programs do little more than obscure, or greenwash, these facts.

We call on nonprofit organizations, regulators, and academics alike to not let the fracking industry off the hook with such simplistic, performative, and too-easy-to-achieve gestures as those proposed in RSG certifications. As currently structured, these programs benefit natural gas drillers financially without proving any authentic commitment to environmental, social, and governance values.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts