New research predicts that green hydrogen — a clean fuel produced from water using renewables — will be comparable in cost and likely cheaper than blue hydrogen by 2030. This is much sooner than what the blue hydrogen industry is estimating when advocating for the natural gas-based fuel to be widely adopted — essentially eliminating the only viable argument to invest in blue hydrogen.

“The True Cost of Solar Hydrogen,” the report from a European research team led by the European Technology and Innovation Platform for Photovoltaics, was published September 7 in the journal Solar RRL and concludes that “during this decade, solar hydrogen will be globally a less expensive fuel compared with hydrogen produced from natural gas with CCS [blue hydrogen].” (CCS is carbon capture and storage.)

This is a much different scenario than the argument being made by supporters of blue hydrogen, such as the gas industry and others who are claiming that within a decade green hydrogen will still be at least double the cost of blue hydrogen.

While there is some question about how dirty blue hydrogen is and will be — due to its reliance on gas, a fossil fuel, and carbon capture technology to reduce emissions from its production — no one is arguing that it will ever be cleaner than green hydrogen. Green hydrogen is clean now, whereas blue hydrogen advocates promise that this fuel may be less dirty at some point in the future, but even then, will never have zero emissions.

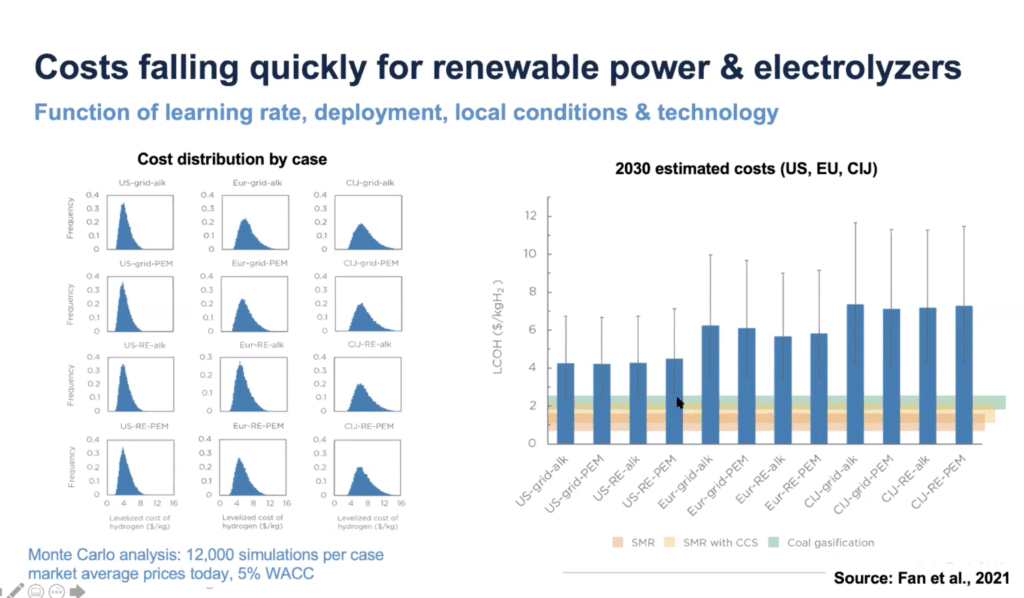

In August, the Columbia University Center on Global Energy Policy (CGEP) held a forum on Zero-C Hydrogen, which included a presentation by representatives of the carbon capture industry — an industry that would experience a financial windfall if blue hydrogen were to be widely adopted. In the presentation, the carbon capture representatives from the Global CCS Institute and CCS consulting firm Carbon Wrangler LLC argued that in 2030 green hydrogen would still be two to three times the cost of blue hydrogen. This information was even presented by Julio Friedmann, founder of Carbon Wrangler and CGEP senior research fellow, on a slide that stated that costs are falling quickly for the two critical components to produce green hydrogen — renewable power and electrolyzers — but that their costs were not falling quickly enough.

This slide, based on simulations provided by Friedmann, puts the expected costs for green hydrogen in 2030 in a range of $4 to $7/per kilogram of hydrogen (kgH2). But Friedmann said that blue hydrogen, which uses carbon capture, would cost slightly above $1.50/kgH2 by the end of the decade.

The new Solar RRL research, however, estimates the cost of green hydrogen will decrease to between $0.82 to $2.11/kgH2 by 2030. By 2050, the paper sees the costs dropping to $0.35 to $1.05.

In May, Jon Andre Lokke, CEO for electrolyzer producer Nel Hydrogen, made a similar estimate for green hydrogen’s prospects in remarks to an online energy event held by energy consultancy Rystad.

“When it comes to blue [hydrogen], I really don’t think from a cost perspective that blue has a chance, to be honest,” Lokke said at the event, adding: “I think with green renewable hydrogen, the cost is going to go down much faster than the analysts think.”

Lokke estimates costs for green hydrogen below $1.50/kgH2 by 2025.

Oil major BP is also investing in green hydrogen and estimates that it can achieve costs of $1.50/kgH2 by 2025.

At the CGEP event on low-carbon hydrogen last month, Alex Zapantis, general manager for the Global CCS Institute, noted that the “cost of hydrogen production is critical.” However he and Friedmann, who, as a CCS consultant, stands to profit from increased investment in carbon capture technology, both used the high costs of green hydrogen to argue the case for blue hydrogen. “The costs associated with this [green hydrogen] are pretty high,” Friedmann remarked.

He also said: “It is important that we see those costs in 2030 as still being more expensive than the low-carbon fossil options.”

It is important to the blue hydrogen industry — which includes natural gas producers like Saudi Arabia, gas logistics companies like Air Liquide, gas turbine manufacturers like General Electric, hydrogen fuel cell companies, and carbon capture firms — that policymakers believe that green hydrogen will be more expensive than blue in 2030 if there is a hope for the industry to be successful. But as new research shows, it isn’t looking like this will be true.

Doubling down on the cost argument, the blue hydrogen industry is also claiming that blending blue hydrogen with green hydrogen could in the future help defray total costs.

“You can reduce that cost by doing a blend of green and blue hydrogen,” Friedmann said.

But the reality is that by 2030, adding blue to the mixture may actually increase costs, if the latest cost estimates for green hydrogen are realized.

As DeSmog reported, blue hydrogen is not a commercially viable option now, and it isn’t possible for companies to pursue it without public subsidies. Zapantis made this clear in response to a question I asked at the event, stating that blue hydrogen “is currently only profitable in very specific circumstances.”

Without the low-cost case, however, any argument for supporting blue hydrogen with public funding falls apart.

A Fossil Fuel Narrative

As it happens, the idea of a hydrogen economy is one largely pushed by the fossil fuel industry. The gas industry knows that a decarbonized economy means the end of natural gas power plants and other dominant uses today. Blue hydrogen was a way for the gas industry to continue for decades.

In May, Lokke, the hydrogen CEO, explained why fossil fuel companies were embracing blue hydrogen so enthusiastically.

“I think it [blue hydrogen] is pushed very much by the big oil companies because they don’t have a choice, and they’re afraid of losing power and the oligopoly position,” Lokke said.

A recent slide from an oil and gas industry conference this September even suggested as much, asking in a presentation whether carbon capture and blue hydrogen would save the natural gas industry.

The first bullet point on the agenda for that conference was: “Making an economic case for blue hydrogen.” This is the case that was made at the CGEP presentation and one the gas industry knows must be done. But the facts don’t support this case. However, even more telling is the bullet point asking: “Is blue hydrogen an end in itself, or a step on the way to green?”

Supporters of blue hydrogen are telling the public that blue hydrogen is the best economic path to green hydrogen — and talking privately about blue hydrogen being “an end in itself.”

Developing blue hydrogen doesn’t make sense, unless you are in the business of producing and selling methane, like the oil and gas industry is.

Funneling money and other resources into blue hydrogen will be a misallocation and distraction from real efforts to decarbonize the global economy. Chris Jackson, the former chair of the UK Hydrogen and Fuel Cell Association, said as much when he explained his decision to resign, calling blue hydrogen an “expensive distraction”.

Considering how much cheaper green hydrogen may prove to be, it would be wise for the world to consider another warning from Jackson: “Our industry is at a very important crossroads, one where the decisions we make will have long-lasting effects.”

The world has dirty, expensive fuels already; it doesn’t need another. Blue hydrogen is the wrong choice.

Why we should be very sceptical of bold claims around blue hydrogen.

— Jan Rosenow (@janrosenow) September 22, 2021

Great piece by @AlexSdelaGarza @TIME. https://t.co/9y88k4Aykk

‘Why are you building it?’

In a scenario where economics and budgets weren’t a concern, spending money to build out both blue hydrogen and green hydrogen infrastructure might make sense.

Indeed, the low-carbon energy transition requires massive investments in infrastructure — from transmission lines to storage to solar and wind generation.

However, since green and blue hydrogen require very different infrastructure, the reality is that the finite resources available need to be applied to solutions that deliver the most benefit in decarbonizing the economy. Choosing to spend money on research and infrastructure to support blue hydrogen and potentially figure out how to make it commercially viable is a misallocation of public resources if the research shows green hydrogen is cleaner and cheaper — despite what the natural gas industry may say.

Jackson, now the CEO of green hydrogen producer Protium, has accused the blue hydrogen industry of misleading politicians about its true economic viability and expectations of large public subsidies. He also recently questioned the industry’s reasoning for building out blue hydrogen infrastructure.

“You’re putting in infrastructure that’s going to take you five years to build and going to be there for 20 years. Everyone should be asking themselves: ‘if this is an asset … in the middle of 2040, [is it] still going to make sense to be running?’ And if not, you have to ask the question right now: ‘why are you building it?’” Jackson recently explained to TIME magazine.

Blue hydrogen requires large investments in carbon capture technology and carbon dioxide (CO2) pipelines to transport the captured carbon from its source to its final storage location. But neither of these investments are required to produce green hydrogen because the wind and solar power used to produce it don’t create emissions that need to be captured like drilling, processing, transporting, and burning natural gas to make blue hydrogen does.

As the TIME article notes, blue hydrogen likely isn’t as clean as industry claims, a valid concern supported by recent research.

If blue hydrogen isn’t clean — and is possibly even dirtier than simply burning natural gas (methane) for power as another study suggests — and if it’s more expensive than clean green hydrogen, there is no rational argument to be made to invest in blue hydrogen.

Limited Role in Decarbonization

Even if blue hydrogen is abandoned in favor of green, though, the gas industry’s push to switch the world to a hydrogen-based economy — including to power cars, generate electricity, heat homes, and more — doesn’t make sense.

Producing green hydrogen requires large amounts of renewable energy. The Hydrogen Council has estimated that by 2050 the world could use 550 million metric tons of hydrogen. Canary Media estimated that would require 18 times the installed global solar power capacity at the end of 2020 or six times the existing wind capacity. That’s a huge amount of energy considering that using that renewable energy to instead directly power electric vehicles, homes, and industry is a far more efficient and cost-effective approach, which wouldn’t require investment in blue hydrogen infrastructure.

Certainly, green hydrogen will be necessary to decarbonize some particularly tricky areas of the economy — including steel production. It also could replace the world’s current hydrogen production, which is made with fossil fuel power using methane as a feedstock and currently represents six percent of the world’s methane consumption.

Aside from those and other specific uses, the idea of a hydrogen economy should be retired, whether it’s blue or green.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts