The tide is turning against Louisiana’s proposed $2 billion Mississippi River sediment diversion project, that supporters say is needed to save the coast from rapid land loss due to subsidence, damage done by the oil and gas industry, extreme weather events, and sea level rise quickened by climate change.

The proposed Mid-Barataria sediment diversion project, is a key part of the state’s $50 billion master plan to restore the rapidly eroding coast. If constructed, the diversion is designed to let the river’s natural land building process restore Louisiana’s disappearing marshland.

The state says it must be built, as it is the best chance for restoring the coast. A growing number of opponents of the project, however, see it as a risky, expensive experiment that, rather than creating the meaningful coastal restoration, will degrade the country’s most productive estuary, harming dolphin populations and the region’s fishing industry.

Earlier this year, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the federal agency responsible for issuing a permit for the project, released a draft Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) on March 5 which is largely supportive of the diversion project. The Corps found that the projected benefits of creating up to 28 miles of self-sustaining marsh in the rapidly eroding Barataria Basin outweigh the likely negative impacts. This includes increasing flooding for those who live near where the project is slated to be constructed, including Black communities in in Myrtle Grove, Hermitage, Grand Bayou, and Happy Jack, along with some Lafitte areas, and killing off a large portion of bottlenose dolphins along with brown shrimp and oysters in the country’s most productive estuary. The draft EIS states that “construction impacts on minority and low-income populations could be disproportionately high and adverse for the population of Ironton.”

“The Army Corps is part of the problem,” Acy Cooper, head of the Louisiana Shrimp Association, said at a recent meeting about the project. He doesn’t think the agency should play a role in making a decision about it; he blames the Army Corps for what he describes as the mess at the mouth of the Mississippi River where there is rapid land loss and a growing deadzone where the river’s polluted river water enters the Gulf.

The diversion project was designed by the Louisiana Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority (CPRA), a state agency formed in the aftermath of Hurricanes Katrina and Rita and tasked with developing a master plan to rebuild and protect the state’s rapidly eroding coast. It plans to open a section of the Mississippi River levee on the West bank of lower Plaquemines Parish and build a channel through it that will reconnect the Mississippi River to Barataria Bay, an area where the river previously deposited land-building sediment before levees were built over a hundred years ago. The diversion will have a controlled, gated system that allows operators to control the flow of water and sediment from the river into Barataria Bay. It will mimic the spring floods that were common before levees were built to contain the river — floods and sediment that built the Mississippi Delta in the first place.

“Though the concept that nature will correct itself sounds good,” scientist Moby Solangi, the president and executive director of the Institute of Marine Mammal Studies in Gulfport Mississippi, said when I met up with him at the Institute on June 7, “a manmade problem can’t be cured by nature.”

Solangi, who is strongly opposed to the diversion project, told me he thinks that misnomer is why many have accepted the CPRA’s narrative that the diversion project is the best way to counter Louisiana’s alarming land loss rate without questioning it. But he is hopeful that the EIS will get people to ask more questions.

The CPRA projects that the diversion will create at least 21 square miles of submerged land in the marsh in Barataria Bay over a 50 year period based on elaborate models developed with a team of scientists. The new land will create a barrier to reduce the impact of storm surges and protect the fastest eroding part of the state’s coast. The success of the CPRA’s land building projections are reliant on the agency’s predictions about the level of nutrients in the diverted water, the amount of silt deposited and the rate of sea level rise over the next 50 years.

“There’s no way to rely on predictions of what’s going on 50 years out,” Solangi said, “especially when you have hurricanes with increasingly strong impacts due to climate change. That isn’t how science works.”

I asked CPRA for a response to this claim but didn’t get an answer before publication.

Louisiana State University (LSU) Boyd Professor R. Eugene Turner and his LSU co-authors Erick Swenson and Michael Layne, and Dr. Yu Mo from the University of Maryland, published a peer reviewed study in 2019 that challenges the CPRA’s models. The scientists analyzed two existing Mississippi river diversions using two different kinds of satellite analyses and found an increased land loss in both areas. The land loss caused may be due to the increased nutrient availability for organic soils, greater flooding and physical scouring.

“Using river diversions for wetland restoration is relatively new, complex and expensive, so knowing the long-term consequences makes it important to develop management plans,” Turner said, according to PHYS.ORG

“The river won’t do what it used to do,” Solangi said. He pointed out the river that exists today isn’t like the river it was when it was created. Studies show there is much less sediment in the Mississippi River’s water than there used to be due to a century of manmade water controls and that the river is the second most polluted river in the country. The river carries with it nitrogen, mostly from fertilizers and manure, and other chemicals that are released into the river upstream by 32 states and two Canadian provinces; these chemicals then flow to Louisiana where the contaminated river water has already contributed to a massive dead zone at the mouth of the river.

Since the project was proposed in 2012, it has seen wide support by state leaders and environmental advocacy groups including the Environmental Defense Fund, the National Wildlife Federation, the Audubon Society, the Lake Pontchartrain Basin Foundation, and the Coalition to Restore Coastal Louisiana remains.

But in the last couple of years some state representatives including Louisiana’s Lt. Gov. Billy Nungesser and three of the state’s parish governments, have come out against the project. Nungesser describes it as a costly experiment that will likely end in failure.

Some of those opposing voices are reflected in the more than 41 thousand comments received by the Army Corps to the EIS draft before the public comment period closed on June 3. The Corps is expected to release its final EIS in 2022 after reviewing all of the comments.

In that mix are comments submitted by the Marine Mammal Commission, an independent government agency charged by the Marine Mammal Protection Act to further the conservation of marine mammals and their environment. They state that the diversion “is expected to have immediate, permanent, and major adverse impacts” on the dolphins. The commission is calling for the project to be revamped or stopped completely due to the harm it will cause the dolphin population in the diversion’s path.

There is also a joint comment from the Animal Welfare Institute, the Humane Society of the United States, the Oceanic Preservation Society, the International Marine Mammal Project of the Earth Island Institute, Ocean Conservation Research, the Center for Biological Diversity, the Humane Society Legislative Fund, Cetacean Society International, and the New York Whale & Dolphin Action League, that states a desire to dispel past media mischaracterizations indicating that “the NGO community” is fully supportive of this project. “We support Gulf of Mexico restoration, but in light of the information presented in the DEIS, we cannot support the proposed sediment diversion,” it states.

Two days before the public comment period closed on the EIS statement, I attended a June 1 CPRA public meeting in Buras, Louisiana, a small town reliant on the seafood industry near the tip of Plaquemines Parish. The Parish is on a thin peninsula that the Mississippi River spans to its end in the Gulf of Mexico.

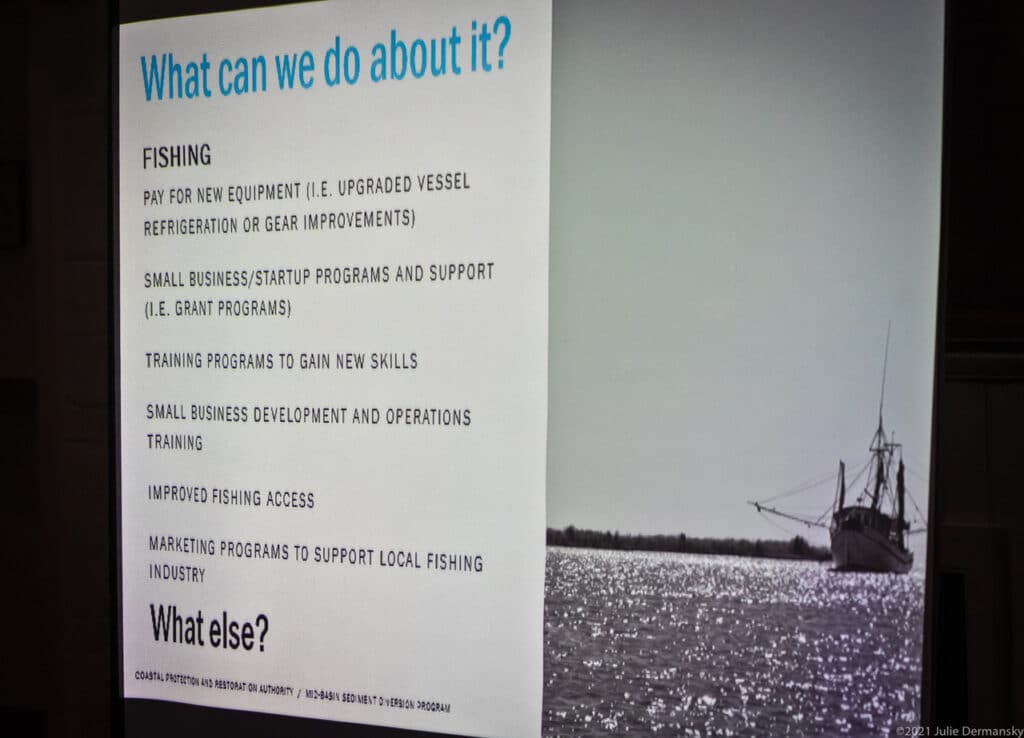

The CPRA’s notice for the meeting said it was conceived to foster a discussion about mitigation solutions to the impacts of the diversion project. The agency has so far earmarked $305 million for mitigation if the project is approved — money that could be spent on a variety of things including programs that might elevate roads, ways to help commercial fisherman transform their business in ways to address the diversion’s impact, providing funding to upgrade boats with refrigeration and more efficient engines to make longer trips possible if the nearby waters of Barataria Bay are no longer suitable to catch anything.

At the meeting, the CPRA encouraged the handful of people that came to fill out questionnaires asking what they wanted mitigation money for but it’s unclear whether anyone did.

Instead of sharing ideas about how the CPRA might help mitigate negative impacts to the community, the discussion at the meeting focused on the community’s desire for the CPRA to come up with an alternative plan to protect the coast.

The Buras community members from Plaquemines Parish at the meeting were united in their belief that dredging is a much more reliable solution to build land and protect the coast than the diversion project. They are calling for a massive dredging project that will build land much faster than the diversion project and won’t destroy the estuary.

Brian Lezina, CPRA’s chief of planning, reminded those who attended the meeting that the CPRA is already working on dredging projects that are part of its master plan for coastal restoration, but argued that without diversion projects, the coast can’t be saved.

In an opinion piece published by the Advocate on May 31, Louisiana’s Lt. Gov. Nungesser made a case against the diversion project and also called for dredging. “We can build over 200 miles of land much quicker and safer for our wildlife and our culture than with the billions CPRA is proposing.” He cited a dredging project that he oversaw when he was president of Plaquemines Parish that helped protect the coast from oil that was washing up from the BP oil disaster in 2011.

A couple days later Gov. John Bel Edwards expressed support for the CPRA’s diversion project in a piece also published by the Advocate. “While we have made and will continue to make massive strides through dredging,” he wrote, “it cannot address the extent of the problems we’re facing. This process, while effective in building land, doesn’t sustain itself long-term and results in a continuous need for more time, money, and sediment to sustain these projects.” This is the same argument that the CPRA continues to make.

Brad Barth, the CPRA’s diversion program manager, told the community members at the June 1 meeting, who overwhelmingly oppose the project, that they would have to agree to disagree on the best way to save the coast, but pointed out at least there was one thing they all agreed on: “the need for coastal restoration.”

Kindra Arnesen, who runs a family fishing business and has been a fierce advocate for her community since the BP oil spill, thanked Barth for acknowledging that the community members at the meeting support coastal restoration. She pointed out that until recently, “anyone who makes their living from the seafood industry who spoke out against the project were labeled greedy, with a mindset of ‘use it to we lose it’ which is the furthest from the truth,” she said.

Arnesen asked how $305 million for a mitigation funds could possibly be enough to compensate what the shrimpers in her community will lose if the diversion is built. She compared that figure to the $254 million mitigation fund that was set aside for one season’s damage to the fishing communities impacted by multiple openings of the spillway in 2019.

In 2019, unusually high levels of water in the Mississippi River prompted the U.S. Army Corps to open a spillway just north of New Orleans, twice in one year, diverting trillions of gallons of the river’s water into the Breton Sound, which feeds into the Mississippi Sound. The influx of river water in the brackish wetlands reduced salinity levels and increased nutrients leading to the deaths of about 330 dolphins and devastating crabs, oyster, and brown shrimp in those areas.

Arnesen and others, including Solangi, see that occurrence as an indicator of what will happen if the Barataria Bay diversion project goes ahead because it will release the same river water into the nearby Barataria Bay.

“If we can’t stay here and make a living, are you here today to be prepared to tell me that you can come buy my house buy my boats, buy all of my equipment, buy all of my permits, pay for me to move and set me up somewhere else for $305 million. Me and all of my colleagues in this parish that houses the largest commercial fishing fleet in the lower 48,” Arnesen demanded to know. “When we are sitting here with a dead fishery, and have a bunch of bills to pay, how are you going to mitigate those damages?” she continued.

She also questioned why it was possible for the project to get a waiver from the Marine Mammal Protection Act (MMPA), the federal law that protects species like dolphins by protecting their habitat. She pointed out that the diversion project also needs waivers for the Endangered Species Act (covering sea turtles) and the Magnuson Stevens Fishery Act (covering essential fish habitats) and said any project that needs so many waivers from federal laws should be suspect.

Plaquemines Parish councilman Mark “Hobbo” Cognevich, representing District 9 where the meeting was held, asked the CPRA representatives if they know how much money was paid to former Senator Mary Landrieu to get Louisiana a waiver from the Marine Mammal Protection act. Brian Lezina, Chief of Planning for the CPRA, shrugged and said he didn’t know.

The CPRA has paid at least $70,000 to the Washington, D.C.-based environmental lobbying firm Van Ness Feldman, where Landrieu is a lobbyist, to help expedite the permitting of the diversion project. The agency got Congress to pass a one-paragraph waiver to the Marine Mammal Protection Act that now only requires the state of Louisiana to monitor the diversion’s impact on dolphins instead of protecting them.

Retired U.S. Army Major Tracy Riley, president of the NAACP’s Algiers/Gretna/Plaquemines Parish chapter, asked the CPRA representatives what was being done to protect the lower income Black community of Ironton that is located about a mile south of where the diversion project is slated to be built.

“There are human remains — three grave sites — that I’m concerned about,” Riley said. “If you are going to put that project through there [Ironton] I’m concerned about that. Those considerations need to be looked at.” CPRA’s Lezina responded that “there is no displacement or relocation of the community of Ironton.”

That surprised Riley because the Corps’ EIS states: “The project is expected to cause minor to moderate permanent adverse impact on economy, population, housing and property values, tax revenues and public service and community cohesions in communities near the immediate outfall area (within 10 miles north and 20 miles south) outside of flood protection due to increased tidal flooding and outmigration,” an area that clearly includes Myrtle Grove, Hermitage, Grand Bayou, and Happy Jack, along with some Lafitte areas. The draft EIS states “the operation of the proposed Project” could lead to “major, permanent, adverse impacts on commercial fisheries, and subsistence fisheries. These impacts could be disproportionately high and adverse on some low-income and minority populations in the Project area as compared to the No Action Alternative” which includes Ironton.

Riley told the CPRA representatives that she wants to make sure that there is equality and justice for all, and expressed concern that she didn’t see anyone taking notes or recording the conversation despite the CPRA asking those who attended to help with solutions to the project.

“While you don’t see us feverishly scribbling right now,” Lezina explained, it is because no one at the meeting had yet talked about solutions when it comes to mitigation. “We haven’t heard anything other than [complaints] about the project — but we are here to hear about solutions.”

In a call with me after the meeting, Riley said that it appeared little has been done to include members of the Black community that make their living in the seafood industry in the conversation. The absence of a Vietnamese translator at the meeting also troubled her, as she assumes the CPRA is aware that Plaquemines Parish has a sizable Vietnamese community that relies on the seafood industry.

Rocky Ditcharo, owner of a shrimp dock and an outspoken critic of the project who has a large financial stake, alluded to conflicts of interest and probable corruption of those involved in the project, a concern that echoed Lt. Gov Nungesser who wrote that he is “deeply concerned that the diversion project, as proposed, is nothing more than another insider deal designed to provide a few well-connected powerbrokers with huge contracts at the expense of every Louisianan.”

On June 12, I met with Ditcharo on his dock while shrimp boats were bringing in their catch. He told me that he is confident the blanket acceptance of this project is a thing of the past. A regular at all of the meetings related to the diversion projects, he noticed at the June 1 meeting that “the tone of the meeting was more defensive than usual and the fact they held it during shrimp season is telling. They knew if they did that, almost no one would show up.”

Ditcharo made that accusation at the June 1 meeting, demanding to know who chose the date. Lezina took responsibility for choosing the date but pointed out that there was nothing sinister about it, reminding Ditcharo that they have had plenty of meetings in the Parish about the project already.

I also met up with Cooper, on Ditcharo’s dock, who also regularly attends public meetings about the diversion project. “The CPRA made the mistake of thinking we are stupid,” Cooper said. “The harder they try to push this on us, the more they spend on PR, the more we know we are winning.”

Shrimping is his family’s heritage, something he intends to pass on to his grandchildren. Packing up and moving away isn’t a viable option for him or many others in the seafood industry.

“Some people assume that the dolphins can just move to another area when their habitat starts getting inundated with polluted river water but it doesn’t work like that.” Cooper said. “They are territorial animals that live in pods, and will remain in the same place even if doing so kills them.”

Dolphin expert Solangi, told me the same thing. “Dolphins, like people, don’t move away just because a new danger is introduced into their environment.” He used the Gulf Coast as an example pointing out how many people rebuild in the same place after storms destroy their home instead of moving away.

CLARIFICATION 06/24/2021: This article was updated to clarify which communities may be impacted by flooding including: Myrtle Grove, Hermitage, Grand Bayou, Happy Jack and some Lafitte areas. The story has also been updated to clarify that Ironton may experience construction impacts.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts