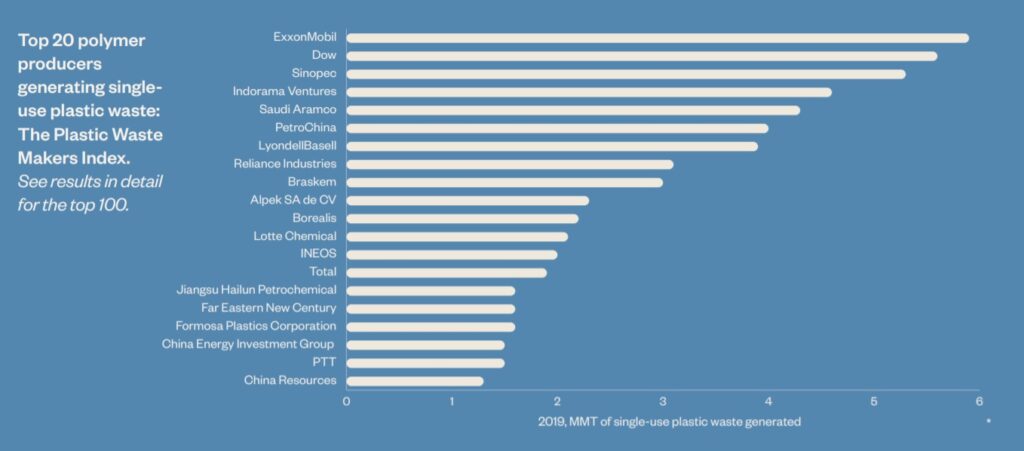

ExxonMobil is the world’s single largest producer of single-use plastics, according to a new report published today by the Australia-based Minderoo Foundation, one of Asia’s biggest philanthropies.

The Dow Chemical Company ranks second, the report finds, with the Chinese state-owned company Sinopec coming in third. Indorama Ventures — a Thai company that entered the plastics market in 1995 — and Saudi Aramco, owned by the Saudi Arabian government, round out the top five.

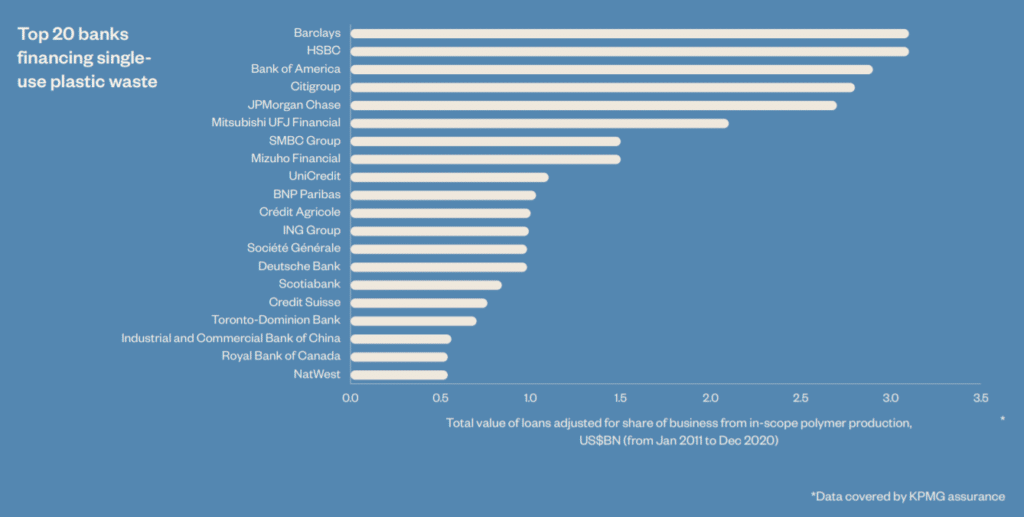

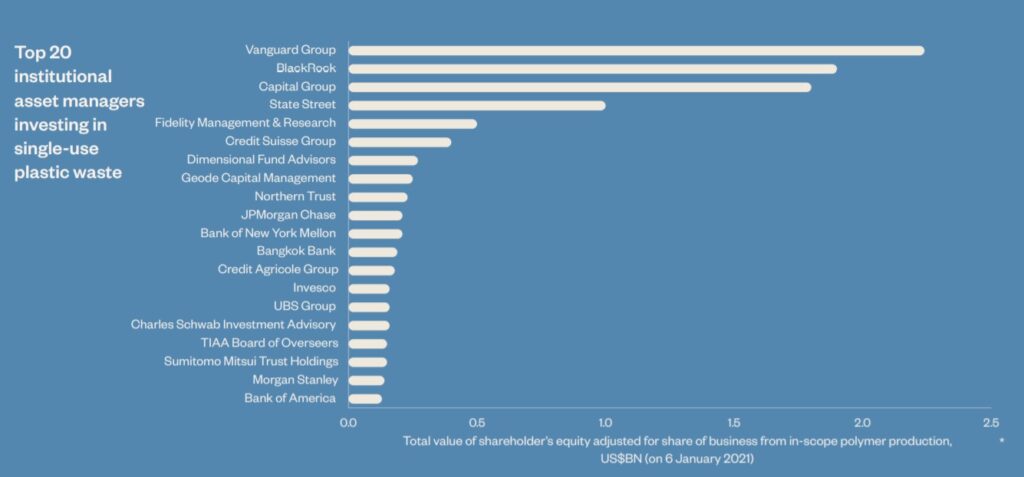

Funding for single-use plastic production comes from major banks and from institutional asset managers. The UK-based Barclays and HSBC, and Bank of America are the top three lenders to single-use plastic projects, the new report finds. All three of the most heavily invested asset managers named by the report — Vanguard Group, BlackRock, and Capital Group — are U.S.-based.

“This is the first-time the financial and material flows of single-use plastic production have been mapped globally and traced back to their source,” said Toby Gardner, a Stockholm Environment Institute senior research fellow, who contributed to the report, titled The Plastic Waste Makers Index.

The report is also the first to rank companies by their contributions to the single-use plastic crisis, listing the corporations and other financiers it says are most responsible for plastic pollution — with major implications for climate change.

“The trajectories of the climate crisis and the plastic waste crisis are strikingly similar and increasingly intertwined,” Al Gore, the former U.S. vice president, wrote in the report’s foreword. “Tracing the root causes of the plastic waste crisis empowers us to help solve it.”

The world of plastic production is concentrated in fewer hands than the world of plastic packaging, the report’s authors found. The top twenty brands in the plastic packaging world — think Coca Cola or Pepsi, for example — handle about 10 percent of global plastic waste, report author Dominic Charles told DeSmog. In contrast, the top 20 producers of plastic polymers — the building blocks of plastics — handle over half of the waste generated.

“Which I think was really quite staggering,” Charles, director of Finance & Transparency at Minderoo Foundation’s Sea The Future program, told DeSmog. “It means that just a handful of companies really do have the fate of the world’s single-use plastic waste in their hands.”

Meanwhile, the report suggests that public policy responses to the threats posed by plastic pollution have focused further along the supply chain, where things become more fragmented.

“Government policies, where they exist, tend to focus on the vast number of companies that sell finished plastic products,” the report finds. “Relatively little attention has been paid to the smaller number of businesses at the base of the supply chain that make ‘polymers’ — the building blocks of all plastics — almost exclusively from fossil fuels.”

While there are about 300 polymer producers currently operating worldwide, just three companies — ExxonMobil, Dow, and Sinopec — combined are responsible for roughly one out of every six pounds of single-use plastic waste, the report concludes.

In 2019, for example, more than 130 million metric tons of plastic was used just once and then discarded. ExxonMobil, the report concludes, was responsible for creating 5.9 million tons of that single-use plastic waste in 2019, with Dow right behind it, generating 5.6 million tons that year.

Neither ExxonMobil nor Dow responded immediately to a request for comment.

Meanwhile, 20 of the world’s largest banks lent nearly $30 billion that was used for the production of new single-use plastics, the report finds. That funding represents about 60 percent of the commercial finance that funds single-use plastics. An additional $10 billion in investment in new single-use plastics has come from 20 institutional asset managers, like Vanguard and BlackRock.

“Through our Investment Stewardship program, Vanguard regularly engages with companies on issues that are financially material to their long-term value and sustainability, including climate issues and environmental matters,” Vanguard spokesperson Alyssa Thornton said in an email to DeSmog. “We expect company boards to oversee climate and environmental risks and provide investors with clear disclosures of their risk oversight and decision-making processes. Importantly, we do not dictate company strategy, or operational or financial decisions; rather, we hold company board’s responsible for being aware of such risks and opportunities as part of a foundation for making the most sustainable long-term decisions.”

Barclays did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

Virtually all single-use plastic comes from fossil-fuel based feedstocks, the report adds.

“One of the key findings of the report is that single-use plastics today is 98 percent fossil fuel-based,” Charles told DeSmog. “And that in itself is really, we say, the source of the plastic waste crisis. And that’s because if you’re only making new plastics from new fossil fuels, you’re taking away the commercial incentive, you’re undermining the commercial incentive to collect this plastic and to turn it into recycled plastic products.”

The report grades plastic manufacturers based on their preparation to transition away from fossil fuels and towards recycling — and found that most of the largest producers not only have made very little progress in that direction to date, they haven’t even set targets that would push them towards a “circular” model involving recycling.

“Over 50 of these companies received an ‘E’ grade — the lowest possible — when assessed for circularity, indicating a complete lack of policies, commitments, or targets,” the report found. “A further 26 companies, including ExxonMobil and Taiwan’s Formosa Plastics Corporation, received a ‘D-’ due to their lack of clear targets/timelines.”

In fact, fossil fuel producers appear to be counting on that failure to move towards recycling. “Two of the biggest markets for fossil fuel companies — electricity generation and transportation — are undergoing rapid decarbonization, and it is no coincidence that fossil fuel companies are now scrambling to massively expand their third market — petrochemicals — three-quarters of which is the production of plastic,” Gore wrote. “They see it as a potential life raft to help them stay afloat, and they’re telling investors that there’s lots of money to be made in ramping up the amount of plastic in the world.”

In a statement on the report, the American Chemistry Council pointed to the use of plastics in products like solar panels and wind turbines to highlight the role that plastics — though not single-use plastics — play in renewable energy. “The world needs plastic to live more sustainably, and America’s plastic makers are leading the development of solutions to end plastic waste,” the Council said. “We’re innovating and investing in efforts to create a more circular economy, where used plastics are systematically remanufactured to make new plastics and other products. In the last three years, the private sector has announced $5.5 billion in U.S. investments to dramatically modernize plastics recycling.”

Meanwhile, the plastics industry remains on track to continue rapidly increasing the amount of new plastic it produces each year, meaning more fossil fuel use — even while other industries are seeking to trim or eliminate their reliance on fossil fuels.

“Our numbers suggest a 30 percent increase in capacity compared to 2019,” Charles told DeSmog. “Now that is not out of line with the historical rate of growth, it’s about 5 percent per year. But if we are to see 5 percent growth in fossil fuel-based, that is a real threat towards the growth of circular plastics and recycling. So I think that’s a real cause for concern.”

As of 2019, plastic producers had created 8.3 billion metric tons of plastic — and 91 percent of it was never recycled, according to one peer-reviewed study. Even from the start, a NPR and PBS Frontline investigation found, industry insiders were skeptical that recycled plastic could compete against new production, with one industry insider warning in a speech — in 1974 — that “There is serious doubt that [recycling plastic] can ever be made viable on an economic basis.”

So where does the money for all this come from?

The financing of single-use plastics is complex, involving not only lending and investment by Wall Street fund managers and big banks, but also privately held companies. The report’s list of the top 10 equity owners of polymer producers includes not only state actors and massive asset managers like BlackRock but also private individuals like James Arthur Ratcliffe — co-founder and majority owner of INEOS, a UK-based petrochemical company.

“Transitioning away from the take-make-waste model of single-use plastics will take more than corporate leadership and ‘enlightened’ capital markets: it will require immense political will,” the report says. “This is underscored by the high degree of state ownership in these polymer producers — an estimated 30 percent of the sector, by value, is state-owned, with Saudi Arabia, China, and the United Arab Emirates the top three.”

The report calls not only for more disclosures from companies and financiers about their ties to plastic production, it also calls for global action to respond to the plastic pollution crisis — starting with a focus on the companies most responsible.

“A Montreal Protocol or Paris Agreement-style treaty may be the only way to bring an end to plastic pollution worldwide,” the report says. “The treaty must address the problem at its source, with targets for the phasing out of fossil-fuel-based polymers and encouraging the development of a circular plastics economy.”

That’s in part because the plastic waste crisis and the climate crisis share one other thing in common — their impacts are global in scope.

“The plastification of our oceans and the warming of our planet are amongst the greatest threats humanity and nature have ever confronted,” Dr. Andrew Forrest, chairman and founder of the Minderoo Foundation, said in a statement accompanying the report. “And we must act now.”

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts