On May 6, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) inspector general issued a report rebuking the agency for failing to protect fenceline communities in 19 metropolitan areas from chloroprene and ethylene oxide, toxic chemicals used in industrial processes. The report directs the agency to review its rules, as required by the Clean Air Act, for both of these carcinogenic air pollutants, which newer scientific evidence has found raise the cancer risk for people living near facilities emitting them.

One of these communities is a low-income, African-American community in St. John the Baptist Parish, Louisiana, situated near the Denka Performance Elastomer plant in LaPlace. St. John holds the dubious distinction of being the only U.S. community exposed to both toxic chemicals cited in the EPA watchdog report.

The Denka plant, formerly owned by DuPont, is the only facility in the country that emits chloroprene, a by-product of manufacturing the synthetic rubber known as neoprene, which is used to make items such as wetsuits. Located along the Mississippi River, Denka is one of many chemical plants and refineries in a stretch of heavily industrialized land between New Orleans and Baton Rouge known as Cancer Alley.

According to the EPA’s most recent National Air Toxics Assessment, the community that lives closest to the Denka plant — in St. John the Baptist Parish — has the nation’s highest risk of developing cancer from air pollution. Most of the increased cancer risk comes from Denka’s chloroprene emissions, according to the inspector general report. However, it also notes that “a significant portion” of that risk is compounded by the additional exposure to ethylene oxide emissions from Union Carbide and Evonik plants, found not far away on the banks of the Mississippi River.

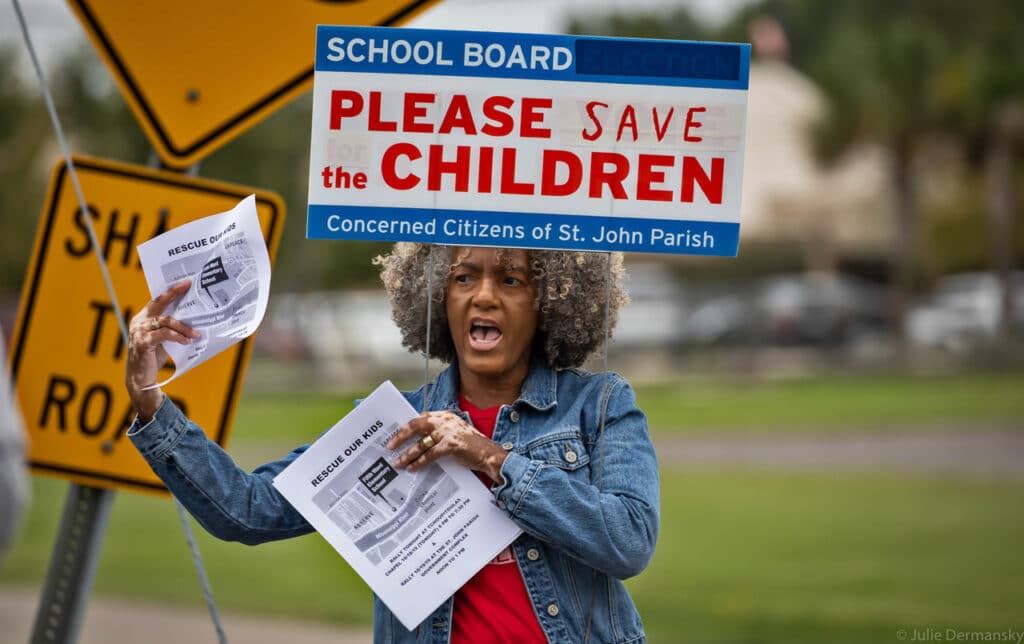

More stringent rules to protect this community can’t come fast enough, says Robert Taylor, founder of the community group Concerned Citizens of St. John. The same day the inspector general released its report, the nonprofit law firm Earthjustice, working on behalf of Taylor’s group, filed a petition calling on the EPA to force the Denka plant to immediately reduce toxic air emissions and require fenceline air monitoring for chloroprene and ethylene oxide. In addition, the petition is pushing for an investigation of whether the Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality (LDEQ), which permits the Denka plant and other nearby facilities and receives federal funding to assess the health impacts of chloroprene emissions, violated the community’s civil rights by discriminating against a protected group under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act.

Their emergency request also calls out potential health risks to — and the resulting need to protect — students at the Fifth Ward Elementary School, a public school less than a half mile from the fence line of the Denka plant. Despite requests from the concerned citizens group, the St. John the Baptist Parish School Board has not relocated students from this school even though it is so close to a facility releasing elevated levels of toxic air pollution.

Community members only learned about the health risks from chloroprene emissions in 2016, despite being subjected to those emissions for over four decades. Denka claimed it didn’t know about the dangers of chloroprene when it bought the plant from DuPont in 2015, and in 2016 the company agreed to install costly control technology to reduce these emissions.

Despite installing such devices — which resulted in major cuts in Denka’s chloroprene emissions — almost five years later the facility’s chloroprene emissions still consistently exceed EPA’s suggested cancer risk level of 0.2 micrograms per cubic meter.

Taylor doesn’t think his community should have to tolerate toxic emissions any longer. He is now calling for the government to shut down the plant until it can prove that the chemicals it releases aren’t harming the surrounding community.

The inspector general’s report called on the EPA to move quickly in updating the regulation of chloroprene and ethylene oxide in order to reduce cancer risks for an estimated 424,000 people.

In 2010, the EPA reclassified chloroprene as a likely human carcinogen and in 2016 determined that ethylene oxide was a confirmed carcinogen. Despite these conclusions, the agency has not reviewed or changed its emission standards for either chemical in the years since.

“Minority and low-income populations are disproportionately impacted by chloroprene and ethylene oxide emissions,” the inspector general report said. It also pointed out that an EPA environmental justice screening tool determined that “100 percent of the people living in the same census block group where Denka is located are minorities and 49 percent of them are low-income.” The watchdog agency went on to warn that EPA’s failure to review its regulations for these chemicals potentially violates a 1994 executive order from the Clinton administration that required the EPA to address environmental justice issues.

While the Concerned Citizens of St. John welcomed the inspector general report, the group remains frustrated by the lack of immediate action against the Denka plant to limit their cancer risks today.

“We have been bombarded with chloroprene and 27 other chemicals’ emissions for 50 years,” Taylor told me. “The plant needs to be shut down until it can limit emissions to the level the EPA determined was safe.” He said he found it reprehensible that neither state nor federal agencies have forced the Denka plant to cut its production — which would lower its chloroprene emissions — even during the pandemic when St. John the Baptist Parish and other nearby African American communities were found to be disproportionally impacted by Covid-19.

I asked the LDEQ for a response to the EPA inspector general report. Gregory Langley, LDEQ public relations representative, did not provide a detailed response. The agency has “a legal issue concerning Denka comments,” he told me.

On December 13, 2016 at a St. John the Baptist Parish Council meeting, LDEQ director Chuck Carr Brown told the parish council that the agency could demand that the Denka plant cut production if the state health department deemed its emissions to be a health emergency. At the same meeting, Louisiana’s then-state health officer, Dr. Jimmy Guidry (who has since retired), told the council that he didn’t think the situation in St. John qualified as a “health emergency.” Guidry did, however, acknowledge at the meeting that no one should be exposed to chloroprene.

At that 2016 meeting, Brown stressed that while his agency was working with Denka to bring down its emissions, there is no government standard for chloroprene emissions. He emphasized that the EPA’s suggested threshold level to protect human health was just that, a suggestion or a guideline, and that people should not get caught up on that number.

NOLA.com reported that Denka’s spokesman David LaPlante disagrees with the Concerned Citizens group’s claim of increased cancer incidences near the plant. He cited studies from the Louisiana Tumor Registry, the state’s cancer registry, which have not found a difference in the rate of cancer cases near the Denka plant when compared to state averages.

Wilma Subra, an environmental consultant who has worked with the St. John community group since 2016, said regulators and the company should not dismiss the EPA’s higher cancer risk levels just because the Louisiana Tumor Registry’s numbers don’t currently show a higher rate of cancer deaths around Denka’s plant than other parts of the state. There are complicating factors making it difficult to record accurate cancer incidences, says Subra, adding that now due to the pandemic, a lot of those people exposed to ethylene oxide and chloroprene emissions may have undiagnosed associated cancers, but if they die of Covid, they would not be counted on the tumor registry.

While Louisiana regulators have not classified the situation in St. John the Baptist Parish as a health emergency, Subra thinks the situation is critical because of the community’s long-term exposure to chloroprene and other emissions from Denka, along with carcinogenic ethylene oxide emissions from two other plants nearby.

“It is totally unacceptable for those community members to have to breathe that air every single day,” she said.

While Subra considers the EPA inspector general report to be a great win for the St. John the Baptist community, she acknowledges it won’t change their air quality tomorrow.

An EPA spokesperson confirmed that the agency’s timeline for reviewing and potentially updating its rules for various industries that emit ethylene oxide or chloroprene will take several years, though the EPA is already working with state and local air agency partners “to identify opportunities for early emissions reductions” for ethylene oxide. “For each of these complex rules, the Agency will work to develop up-to-date, accurate information about emissions from the industries, share information with surrounding communities, and seek public input during the rulemaking process.”

The anticipated completion date for most of these reviews is 2024.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts