President Joe Biden, in one of his first actions after entering the White House, signed an executive order Wednesday canceling the permit for the Keystone XL (KXL) pipeline. The move blocks construction of the 1,200-mile pipeline, and puts an end to a saga that has persisted for more than a decade.

The cross-border pipeline would have carried 830,000 barrels per day of Canadian tar sands oil to the Gulf of Mexico, where it would be refined and exported, providing a crucial outlet for landlocked oil from Alberta. But the mundane infrastructure project became a symbol of the broader fight against climate change, sparking a sustained campaign against drilling and fossil fuel infrastructure across the continent.

“We only achieve huge wins like this by speaking out together,” Madonna Thunder Hawk of the Lakota People’s Law Project said in a statement. “Rescinding KXL’s permit is a promising early signal that the new administration is listening to our concerns and will take issues of climate and Indigenous justice seriously. We have to insist that it not stop there.”

The cancelation of Keystone XL cements a legacy of climate activism, a movement that has grown into a powerful force in American politics. The end of the pipeline is also a major victory for the many Native American tribes who have consistently been at the forefront of battles against fossil fuel infrastructure.

At the same time, many more pipelines are under construction or are on the drawing board, having eclipsed Keystone XL long ago in terms of importance to the industry.

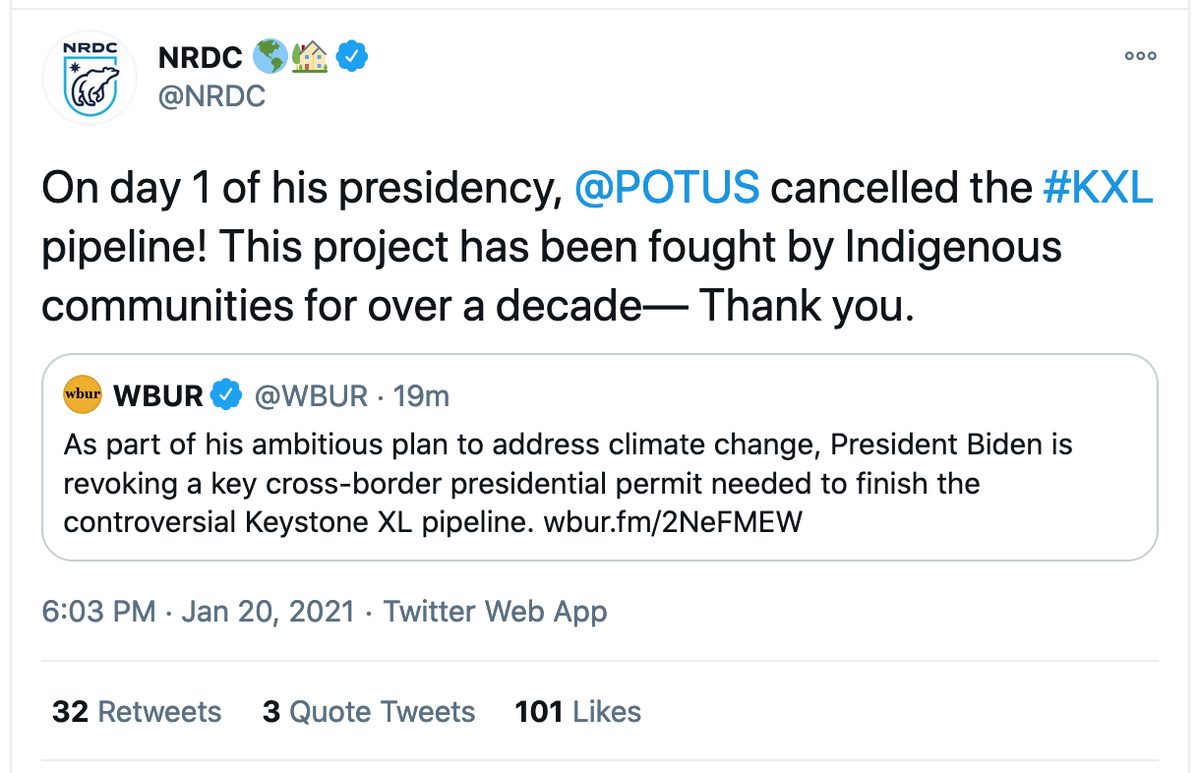

Tweet via NRDC.

In 2015, then-President Barack Obama denied a key permit for the project, citing the need to lead on climate, a move that at the time seemed like the final word on the matter. However, President Donald Trump immediately revived the pipeline proposal when he assumed office in 2017.

Despite the backing of the U.S. government, the pipeline project faced some legal hurdles during the Trump era that delayed construction. President Biden’s executive order issued on January 20 once again puts the project on ice. TC Energy, the pipeline’s sponsor, said it would suspend operations and “consider its options.”

“We applaud President Biden’s swift action to rescind Keystone XL’s improperly obtained permits and stop this disastrous project in its tracks yet again,” David Turnbull, Strategic Communications Director at Oil Change International, said in a statement. “Keystone XL would be a disaster for our climate, a disaster for First Nations communities at the source of the tar sands in Canada, and a disaster for communities across a broad swath of our country along its route.”

The Power of Activism

The fatal blow to Keystone XL is a major victory for a coalition of opponents who have fought the fossil fuel project for well over a decade. The fight defined a new era for the environmental movement.

In the early Obama years, national environmental groups placed a lot of faith in legislative efforts at the federal level without building power at the grassroots — a strategy then symbolized by the failed cap-and-trade bill in 2009. In the wake of that defeat, and with the legislative route cut off after Republicans swept the House of Representatives in 2010, the Obama administration turned to executive action. One of those key moves included introducing in 2014 the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s Clean Power Plan to regulate climate emissions from power plants, though its implementation was eventually blocked by the U.S. Supreme Court as the plan was ensnared in legal challenges.

At that point, environmental groups took the climate fight to the grassroots level. And instead of looking at market-based solutions like cap-and-trade, they turned to a “keep it in the ground” strategy, focusing on blocking new supplies of oil, gas, and coal, as well as fossil fuel infrastructure.

And the science supports activists’ calls to keep fossil fuels in the ground. The United Nations says that governments need to wind down fossil fuel production at a rate of six percent per year over the next decade in order to have a shot at meeting a 1.5-degree Celsius warming target and avoiding catastrophic climate impacts.

This anti-fossil fuel development push, however, was not embraced universally by all environmental groups, and conflicted with President Obama’s “all of the above” mantra when it came to the types of energy actions and solutions he would pursue, but the keep-it-in-the-ground strategy became increasingly mainstream for activists in the second Obama term and into the Trump era.

Amid this rising grassroots action to stop the Keystone XL pipeline came an increasing awareness and recognition on behalf of environmental groups of the importance of Indigenous Rights and concepts related to environmental justice, broadening the narrow focus on greenhouse gases that had characterized many prior efforts.

This awareness, however, did not always come easily. “It has always been a challenge for folks to understand the strategic value of an Indigenous Rights framework when it comes to protecting land and water,” Dallas Goldtooth, an organizer with the Indigenous Environment Network, told DeSmog via email.

Indeed, Indigenous peoples have been at the forefront of pipeline resistance since the earliest days of Keystone XL. Goldtooth pointed out that the fight against Keystone XL began with First Nations Dene families in Northern Alberta who lived close to toxic tar sands operations.

And the campaign against the Dakota Access pipeline in 2016 was led by the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe along with other Indigenous peoples and, to a lesser extent, non-Native allies. Today, some of the largest campaigns against pipelines are also led by Indigenous peoples, including opposition to Line 3, the Trans Mountain Expansion, and the Coastal GasLink pipeline.

More Projects in the Pipeline

But while the defeat of Keystone XL is historically momentous, it raises questions about other routes for Canadian tar sands. After sitting on the drawing board for years, Canada’s oil industry has already turned to alternative pipelines, such as Enbridge’s Line 3 replacement through Minnesota and, even more importantly, the Trans Mountain Expansion from Alberta to British Columbia.

“With Line 3 and TMX [Trans Mountain Expansion], Alberta has sufficient capacity to get its oil to market,” Werner Antweiler, a business professor at the University of British Columbia, told DeSmog.

In fact, scrapping Keystone XL arguably makes these other projects more urgent. “For the federal government of Canada, which has a vested interest in the commercial success of TMX, the cancelation of the KXL project may ultimately be good news because it ensures that there is sufficient demand for TMX capacity,” Antweiler said. “This means it is more likely now that TMX will become commercially viable and can be sold back to private investors profitably after construction is complete.”

This at a time when Keystone XL proved to be an expensive gamble. In 2019, Alberta invested $1.1 billion in Keystone XL in order to add momentum to the controversial project, funding its first year of construction. Now the province may end up selling the vast quantities of pipe for scrap, while also hoping to obtain damages from the United States.

Others are less convinced that the cancelation of one project is a boon to another. Even the Trans Mountain Expansion faces uncertainties in a world of energy transition. “Looking back a century ago, as one-by-one carriage manufacturers shut down as car manufacturers expanded production, prospects for the remaining carriage manufacturers didn’t improve,” Tom Green, a Climate Solutions Policy Analyst at the David Suzuki Foundation, told DeSmog.

“Canada can take its cue from Biden: recognize the costly Trans Mountain pipeline isn’t needed or viable, it doesn’t fit with our climate commitments, and instead of throwing ever more money into a pit, government should invest those funds in the energy system of the future,” he said.

Editor’s Note: This story has been updated to include a statement from Oil Change International.

Main image: Keystone XL pipeline protest at the White House in Washington, D.C., on November 6, 2011. Credit: Emma Cassidy, via tarsandsaction, CC BY 2.0

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts