The disproportionate toll that COVID-19 is taking on the Black community brought environmental justice issues to the forefront during 2020. Calls for dealing with climate change and environmental justice were elevated by president-elect Biden, who spoke about endangered communities in the last presidential debate and on his campaign website, calling for environmental justice and “rooting out the systemic racism in our laws, policies, institutions, and hearts.”

That toll is apparent in Louisiana where I continued to document the struggle for environmental justice for DeSmog throughout 2020. These photos are part of an ongoing DeSmog series on the industrial corridor between Baton Rouge and New Orleans known as ‘Cancer Alley’ which hosts more than 100 petrochemical plants and refineries. Environmental racism and pollution have left fenceline communities especially vulnerable to COVID-19.

At the start of the pandemic, Concerned Citizens of St. John the Baptist Parish, a Cancer Alley community group, worried that the industrial sites around their homes might end up releasing even higher levels of air pollution since the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) announced that it was relaxing some of its pollution reporting and monitoring rules for industrial plants due to the pandemic.

The group has been particularly concerned about the nearby Denka plant, which emits numerous toxic chemicals including chloroprene, a likely human carcinogen, that’s used to produce the synthetic rubber Neoprene.

Members of RISE St. James, another Cancer Alley community group focused on stopping new petrochemical plants from being built in St. James Parish, were alarmed about the conversations about racial disparity regarding the virus’s impact by Louisiana officials. They felt that elected officials, more often than not, failed to mention the role pollution plays in compromising the health of many African-American communities that are near refineries and chemical plants, a pollution burden that scientists say increases the risk of severe outcomes from COVID-19.

RISE St. James and allies have been fighting to stop the plastics manufacturing company Formosa from building its proposed $9.4 billion petrochemical complex that would likely more than double the toxic load in their already polluted air.

“Despite so much heartache in 2020, we have seen some success in our fight for clean air this year,” Sharon Lavigne, the founder RISE St. James said on a call. “This year it is becoming clear that the law is on our side. Recent court rulings give me hope that victory will be ours.”

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers announced on November 4 that the agency would reevaluate its wetlands permit for Formosa Plastics. And on November 18, state judge Trudy White sent critical air permits for Formosa’s project back to the Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality (LDEQ), directing the agency to take a closer look at how the plastics facility’s emissions will impact the predominantly Black community living nearby.

Lavigne was also happy to learn on December 19 that a Louisiana district attorney chose not to prosecute her allies, Anne Rolfes and Kate McIntosh — environmental advocates with the Louisiana Bucket Brigade — for delivering plastic nurdles to fossil fuel lobbyists’ homes. They were facing federal charges for a stunt tied to a ‘nurdlefest,’ a December 2019 event in Baton Rouge aimed at raising awareness about plastics pollution.

But Lavigne is painfully aware she and others fighting for environmental justice in Cancer Alley can’t let their guard down. Earlier this month Governor John Bel Edwards announced that Mitsubishi Chemical Corporation (MCC) is considering building a large Methyl methacrylate (MMA) chemical plant in Cancer Alley, and the state is offering the company $4 million incentives to do it.

1. Sharon Lavigne, founder of RISE St. James, with Pam Spees of the Center for Constitutional Rights, and Anne Rolfes, founder of the Louisiana Bucket Brigade, speaking to the press before a St. James council meeting where they asked the council to rescind a land use permit it granted to Formosa after a report was published showing the site has human remains that likely belonged to slaves on Jan. 21, 2020.

2. Wilma Subra, a technical advisor to the environmental advocacy group Louisiana Environmental Action Network going over data on reported chemical releases during the public meeting in Baton Rouge a week after the fire at ExxonMobil’s Baton Rouge refinery on Feb.19.

3. Mary Hampton, President of the Concerned Citizens of St. John The Baptist Parish at a community meeting where David Gray, a regional EPA official, explained changes the agency is making to its ongoing air monitoring of chloroprene in St. John the Baptist Parish on Feb. 11.

4.Sharon Lavigne, the founder of RISE St. James, in St. James Catholic Church on April 8. 2020, where she told me: “Black people are being polluted the most in the 4th and 5th District in St James Parish, so of course we are hit the most by the pandemic. We are already hit by the pollution in the air. The pandemic adds to what we are already going through.”

5. Gail LeBoeuf, a St. James Parish resident taking part in a protest against pollution from petrochemical plants at the St. John the Baptist Government Complex on April 11.

6. Rep. Cedric Richmond speaking to Cancer Alley community members who protested in front of The New Orleans Advocate on April 24. Richmond, who has taken hundreds of thousands of dollars in fossil fuel campaign contributions during his tenure representing the cancer alley area, announced Nov. 12 that he was giving up his seat and joining Biden’s White House team as a senior adviser.

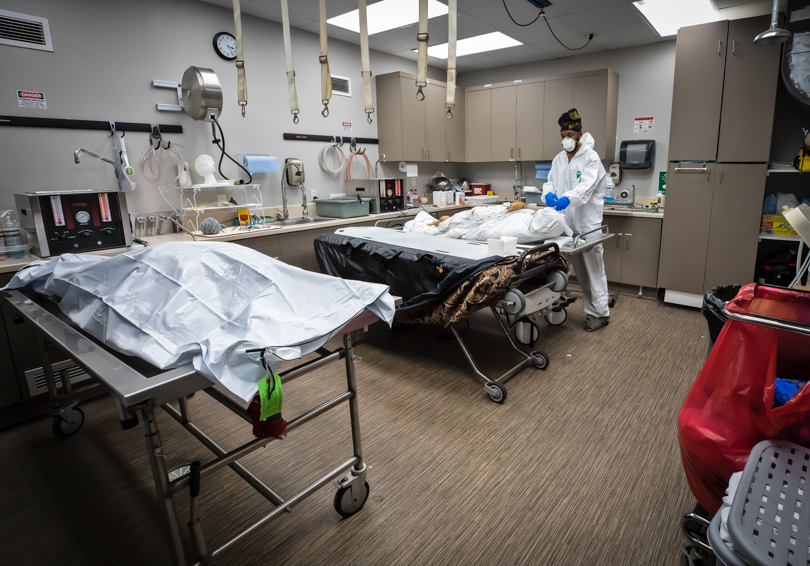

7. Courtney Baloney, the owner of the Treasures of Life funeral home, in St. James Parish, ready to start work on the body of a confirmed COVID-19 victim on May 30.

8. A pregnant woman at a rally in Duncan Plaza in New Orleans on the first of seven days of protest in solidarity with George Floyd on May 30. A coalition of social justice groups, led by Take ‘Em Down NOLA and the New Orleans Workers Group, took to the city’s streets, protesting Floyd’s murder and raising awareness of the many injustices plaguing people of color from May 30 through June 7.

9. Protesters fleeing from a line of police on the Crescent City Connection on June 3 after police began firing tear gas and projectiles at them. The tear gas was fired despite health experts warning that the use of tear gas, a toxic irritant that can cause long-term lung damage, may worsen the spread of coronavirus.

10. Anne White Hat, one of the Indigenous leaders of the L’eau Est La Vie Camp that fought against the Bayou Bridge pipeline, speaking at a rally across from Jackson Square on June 6 in New Orleans.

11. Sharon Lavigne speaking at a Juneteenth ceremony at the site of a former burial ground for enslaved African Americans on the site where Formosa plans to build a petrochemical complex on June 19.

12. Mark Benfield (right), a professor at Louisiana State University, with Dr. Liz Marchio, a local scientist, collecting nurdles under a wharf in New Orleans on August 25.

13. Sharon Lavigne, the founder of RISE St. James at a permit hearing for YCI Methanol Plant in St. James Sept 10, 2020. YCI applied for permits that would let them dump 61 hazardous chemicals into the Mississippi River, right near two St. James drinking water intakes. YCI’s wastewater could affect everyone downriver from their plant, including residents of New Orleans.

14. Residents of Cancer Alley marching with supporters in Lutcher, Louisiana, on October 17 during a protest against Amendment 5, which appeared on Louisiana’s November 3 ballot. If passed, the measure would have allowed manufacturers to negotiate lower tax bills with local governments, giving the petrochemical industry a way to permanently avoid paying property taxes. The amendment was rejected by Louisiana voters.

15. Wilma Subra, technical advisor for LEAN speaking against air permit modifications requested by the Marathon refinery at a LDEQ public hearing on Nov. 10 in St. John the Baptist Parish. If the modifications are approved, the company will be permitted to release more toxic pollution than it already does. Few community members came to the meeting due to the pandemic.

16. Anne Rolfes, founder of the Louisiana Bucket Brigade speaking against a permit modification sought by So LA Methanol, another plant poised to be built in St. James, at an LDEQ permit hearing on November 19.

17. New Orleans advocates for federal action to address the plastic pollution crisis projecting an anti-plastic message onto a New Orleans post office on December 7. Similar projections took place in San Francisco, Houston, Philadelphia, Washington, D.C., and Columbus, Ohio.

LEAD PHOTO: Robert Taylor visiting the Zion Travelers Cemetery, next to the Marathon Refinery, in Reserve, Louisiana where some of his relatives are buried.

All photos by Julie Dermansky for DeSmog

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts