Major players in the U.S. petroleum refining industry — which is experiencing a historic downturn due to the coronavirus pandemic — are attempting to sell refineries, with little luck. Unable to find any buyers, several refineries are becoming stranded assets as they are permanently shut down.

The pandemic continues to set new records in the U.S. almost daily — more than 250,000 people in the United States have died from COVID-19 since February. This mounting crisis is leading to a second round of shutdowns and measures that will limit economic activity and slow the consumption of fuel. Amid this, the refining industry is expected to face a prolonged downturn.

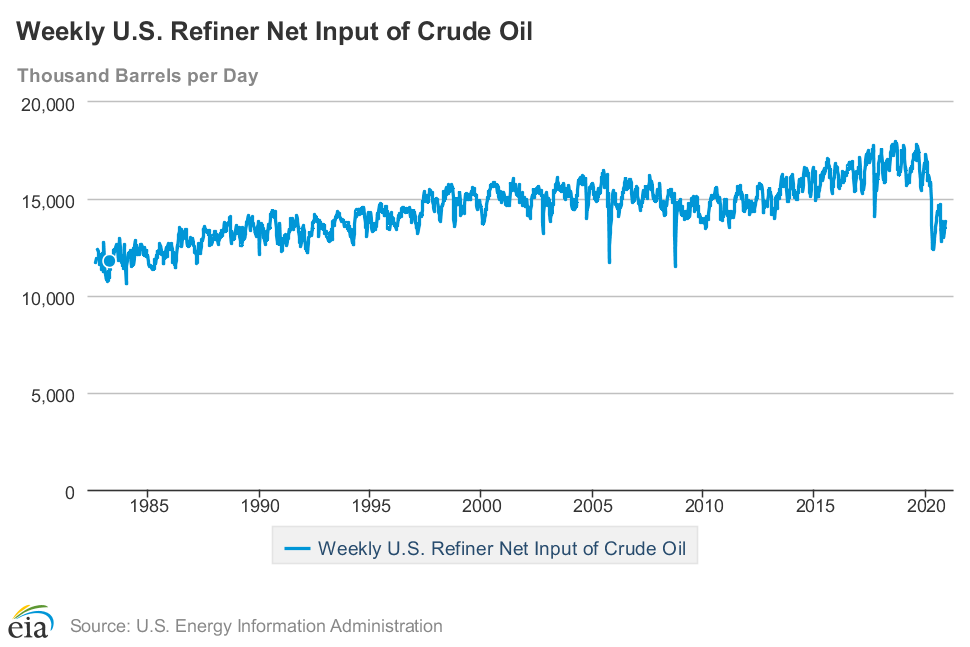

In the second week of November 2019, U.S. refinery inputs totaled 16.0 million barrels per day (mbpd). In the same week in 2020, the total was 13.6 mbpd — a 15 percent decrease.

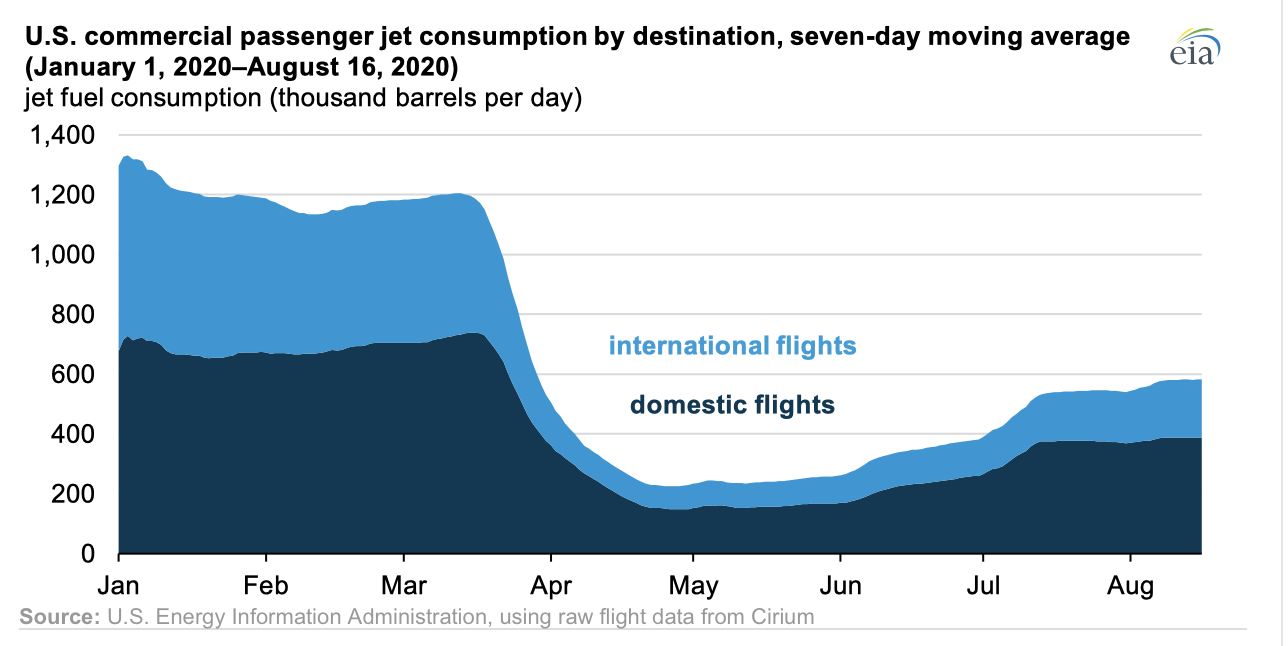

Expectations are for the economy and fuel consumption to return to 2019 levels at some point in the future, with one caveat: The demand for very profitable jet fuel (which accounted for 9 percent of total U.S. refinery output last year) may never return. This change poses a major threat to the basic business model of many refineries.

Weekly Input of Crude Oil to U.S. Refineries (Nov. 13, 2020). Source: EIA

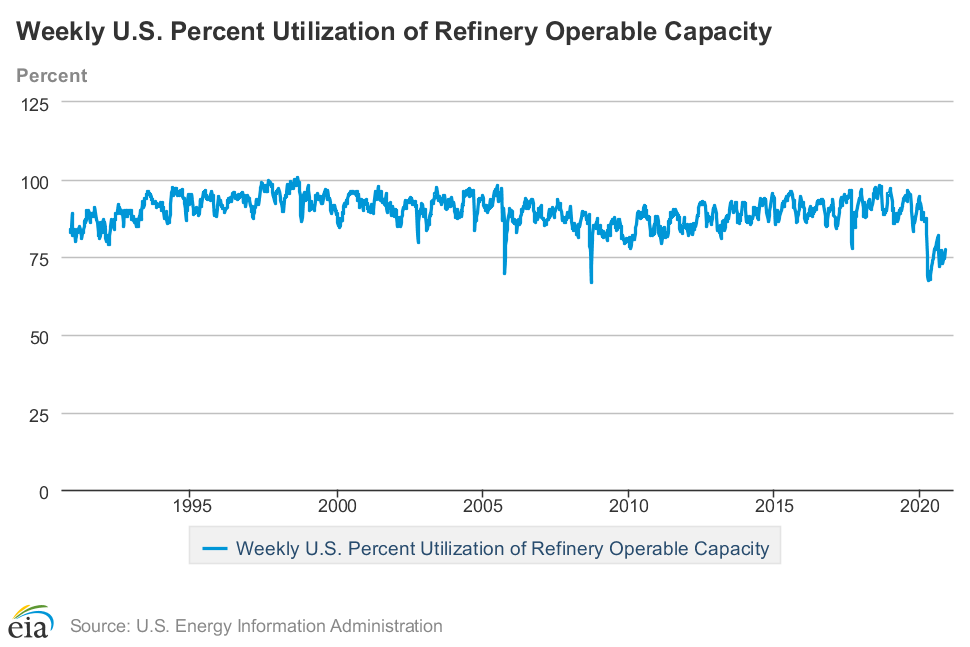

Although plenty of businesses face similar challenges, it may be especially hard for refineries to weather rapid drops in demand. This is because there is a well-established hard limit on how much they can dial back production before it makes more sense to simply shut down the refinery. That limit — reported as percent utilization and known as the “turndown” value — is usually estimated at 70 percent of the maximum possible amount a refinery could produce if it were running at full capacity. Once things drop below 70 percent, refineries face shutdowns, because running the refinery at lower utilization rates no longer makes financial sense.

Weekly U.S. Percent Utilization of Refinery Operable Capacity (Nov 13, 2020). Source: EIA

An analysis by consulting firm RBN Energy notes that if refineries operate below the turndown level, “operations can become erratic,” resulting in the refinery no longer being able to function properly, which leads to decisions to close the refineries instead of attempting to operate below turndown levels.

Since June 2019, there have been seven refinery closures in the U.S., according to RBN Energy. This represents approximately 6 percent of total U.S. refinery capacity.

As an August article in Argus Media pointed out, the U.S. refining industry is facing a structural problem:

“Refiners previously eking out a narrow profit — or acceptable loss — must decide whether their operations justify costly and necessary maintenance. Deferring work risks even more expensive, unplanned shutdowns.”

An industry that is balancing between “narrow profit” and “acceptable loss” is highly likely to see more closures and a reduction in capacity. The International Energy Agency (IEA) recently released a report that estimated that 14 percent of global refining capacity in advanced economies “faces the risk of lower utilization or closure” by 2030, an outcome all the more likely due to the pandemic.

Valero and Marathon, the two largest refiners in the U.S., have said they plan to run at lower utilization rates in the fourth quarter of 2020 compared to the third quarter. And refiner PBF Energy estimates that the U.S. refining industry requires the closure of another 1-1.5 mbpd of capacity, according to a recent report by S&P Global.

Like most areas of the U.S. oil and gas industry, the refining industry was in trouble before the COVID-19 pandemic and the subsequent large drops in demand for its products. The coronavirus has just sped up the timeline of the refining industry’s inevitable decline, adding to the growing list of stranded fossil fuel assets.

Refineries For Sale But Not Finding Willing Buyers

With refineries running close or below turndown levels, it isn’t surprising that some companies have decided to close some refineries altogether. Recent attempts to sell refineries or find new partners to share the risk have not gone well, and so for many there is no other option than to shut down permanently.

“Refineries are struggling right now because demand has collapsed and that has led to severe overcapacity,” Rick Joswick, the head of oil refining analytics at S&P Global Platts, explained to The New York Times in August. Currently, the U.S. is producing more oil than the refineries can process. This type of overcapacity is what led to oil prices going negative in April 2020, and as U.S. oil producers continue to try to increase production, U.S. oil storage is once again approaching its limits.

Oil tanks in America’s most important crude storage hub are filling to the brim once again https://t.co/DLl99Jbqop#OOTT

— Helen Robertson (@HelenCRobertson) November 20, 2020

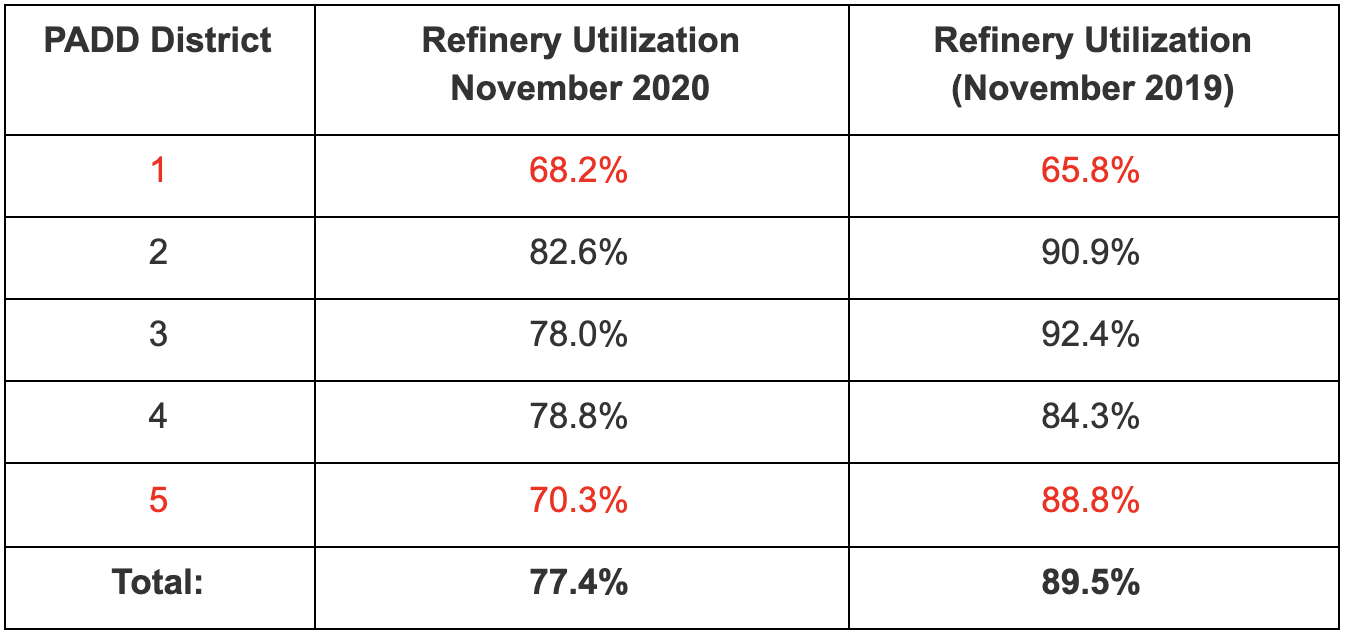

The current utilization rate for the total U.S. refining industry is above 77 percent, safely beyond the turndown rate of 70 percent. However, this level does not reflect the large regional differences in what is happening to refiners.

The Energy Information Adminstration reports on U.S. refineries by region using the five Petroleum Administration for Defense Districts (PADD). The data shows that the East and West coast regions (PADDs 1 and 5) are bearing the brunt of this industry downturn, with the nation’s lowest utilization rates, hovering around 70 percent.

Refinery Utilization Rates by PADD District vs. Year Ago. Source: EIA

The East coast (PADD 1) refining business was running at or near turndown rates before the pandemic, and that trend continues despite the closure of a major refinery outside of Philadelphia following a large explosion in June of 2019. Explosions and accidents are more likely when refineries choose to delay maintenance.

However, the PADD 5 district (which is comprised of five western states and Alaska) is being hit hardest by the impact of the virus and that is where several refinery closures have recently been announced.

This includes Marathon Petroleum, the largest refiner in the U.S. In August, Marathon announced it was indefinitely idling its refinery in Martinez, California, even though it just bought the refinery in 2018. Marathon is also closing its refinery in Gallup, New Mexico. The company is expected to lose $8 billion this year. Phillips 66 also announced in August that it plans to shutter its refinery in California by 2023, with an expected $3.3 billion loss just this year.

The reasons for these shutdowns do not bode well for other refiners. “The reason is changing market conditions in California,” said Jim Anderson, Maintenance Superintendent for the Santa Maria Refinery owned by Phillips 66. “The changing refinery requirements, changing crude oil supplies have all worked kind of against the facility here in Santa Maria and it’s really just no longer economically viable to continue to operate.”

Phillips 66 also announced it would be converting its San Francisco refinery away from processing crude oil to instead producing biofuels from cooking oil, fat, grease, and soybean oil. A similar plan was announced in June by the company HollyFrontier for its refinery in Wyoming.

Oil major Shell has announced plans to sell eight of its 14 refineries by 2025 and recently attempted to sell the Convent refinery in Louisiana before announcing it could not find a buyer. Instead, Shell said it will just close the refinery. In March, the oil giant announced its intention to sell refineries in Washington and Alabama but has not announced any completed sales.

The odds of the Convent refinery reopening are less than 50-50, said John Auers, executive vice president at Turner, Mason and Co., a Houston-based energy consulting firm. He described Shell’s decision to close it as an industry “one-off” decision that he doesn’t expect other Louisiana refinery operators to repeat.

But the poor prospects for refiners isn’t limited to the U.S. S&P Global Platts recently reported on multiple refinery closures or shutdowns in Europe.

In August, The New York Times reported on Delta Airlines’ ill-fated attempt to increase profits by buying a refinery outside of Philadelphia. The story noted that Delta has been looking for a partner to help operate the refinery, but has had no takers. “It’s a refinery that could shut down if nobody wants to buy it,” Auers told The New York Times. “I don’t think Delta is interested in running it longer term. It didn’t play out as they thought it would.”

Jet Fuel Goes From Cash Cow to Financial Albatross

As The Times’ article on Delta explains, jet fuel has historically been known as “Steady Eddie” because it was a “predictable profit maker.” Then the pandemic hit.

The latest weekly report from the Energy Information Administration notes that while U.S. gasoline consumption is down 10 percent compared to the same four week period from a year ago, jet fuel consumption is down 40 percent.

U.S. Commerical Passenger Jet Fuel Consumption. Source EIA

The recent resurgence of the virus and the public health emphasis on avoiding all non-essential travel, particularly by air, mean jet fuel consumption is likely to be one of the last economic areas to recover from the pandemic. At the same time, even when air travel becomes much safer, the move to more remote work and reliance on video conferencing by U.S. businesses may lead to a permanent change in business travel.

“My prediction would be that over 50% of business travel and over 30% of days in the office will go away.” – @BillGates on post-pandemic working habits at the #Dealbook Online Summit https://t.co/U6hXArCenO pic.twitter.com/FF7DKm5AXG

— DealBook (@dealbook) November 17, 2020

Airlines would be devastated if business travel doesn’t return to prior levels. According to a study by Trondent (self-described as a “leader in global travel management solutions”), business travelers account for 75 percent of airline profits, while only representing 12 percent of an airline’s total passengers. If airlines can’t make a profit, they will cut more flights and consume less jet fuel.

COVID-19’s long-term impact on air travel, and its similar impact on U.S. business travel, poses a major financial risk to the U.S. refining industry, which was already facing decline in demand for its products from another change in transportation — the electrification of the U.S. vehicle fleet. As the electric vehicle market surges, major car companies are promising big investments in electric vehicle production.

It’s a perfect storm. The structual decline in demand for fossil fuels comes at the same time one of the industry’s main competitors is rapidly expanding, further eroding that demand. So, as U.S. refineries are shuttered or continue to operate in an ongoing state of “acceptable loss,” it’s extremely likely that refineries will join the rapidly growing list of former oil and gas industry assets that will soon be stranded.

The pandemic has simply accelerated this decline, Rob Smith, director at the energy consulting firm IHS Markit, told the Houston Chronicle. “What was expected to be a long, slow adjustment,” Smith said, “has become an abrupt shock.”

Main image: Sinclair Oil Refinery, Sinclair, Wyoming. Credit: CAJC: in the PNW, CC BY–SA 2.0

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts