There was some speculation that climate-changing emissions might drop this spring as the world went into lockdown to slow the spread of the coronavirus. But, according to a new report by the World Meteorological Organization (WMO), this year’s sudden drop off in travel — and transportation fuel consumption — didn’t lead to sizable declines in planet-heating emissions.

In fact, the three most powerful greenhouse gases continued to rapidly build up in the Earth’s atmosphere in 2020 despite daily emissions falling up to 17 percent during the most severe pandemic stay-at-home orders.

“The lockdown-related fall in emissions is just a tiny blip on the long-term graph,” WMO Secretary-General Professor Petteri Taalas said in a statement accompanying the new report.

The news comes as it’s more critical than ever to seriously tackle rising global emissions. As scientists warned in 2018, current emissions must be cut in half by 2030 if there is any hope of limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit) — the limit after which many severe climate impacts may be irreversible.

Last year, carbon dioxide (CO2) levels reached concentrations not seen in the past three to five million years, the WMO found. And in 2020, CO2 pollution in the atmosphere continued to rise — just at a “slightly reduced rate,” the report said.

The pandemic’s lack of a sizeable dent in CO2 levels is in part because human-caused emissions had been accelerating so rapidly heading into the pandemic and in part because other natural forces are constantly causing CO2 levels to fluctuate in the background, the report found.

This spring’s lockdowns shaved between 0.08 and 0.23 parts per million off the expected rise in the world’s CO2 concentrations, the WMO estimated. Since natural variability can cause fluctuations of up to 1 part per million (ppm), that “means that in the short-term, the impact of COVID-19 confinement measures cannot be distinguished from natural year-to-year variability,” the WMO said.

‘Never Been Seen’ Before

The WMO‘s report, published November 23, also summarizes the evidence on how climate-changing pollution had been accelerating before the pandemic arrived. Over the past few years, the concentration of carbon dioxide pollution in the Earth’s atmosphere has surged at a stunning speed.

“We breached the global threshold of 400 parts per million in 2015. And just four years later, we crossed 410 ppm,” Taalas said. “Such a rate of increase has never been seen in the history of our records.”

It took nearly 60 years for CO2 levels to climb to 400 ppm from the 316 ppm that climate scientists found when they first regularly started collecting measurements at the famed Mauna Loa observatory in Hawaii. Crossing the 400 ppm threshold was considered a “new era” by scientists — a level of carbon in the atmosphere never experienced by humanity and one which will help usher in catastrophic climate change.

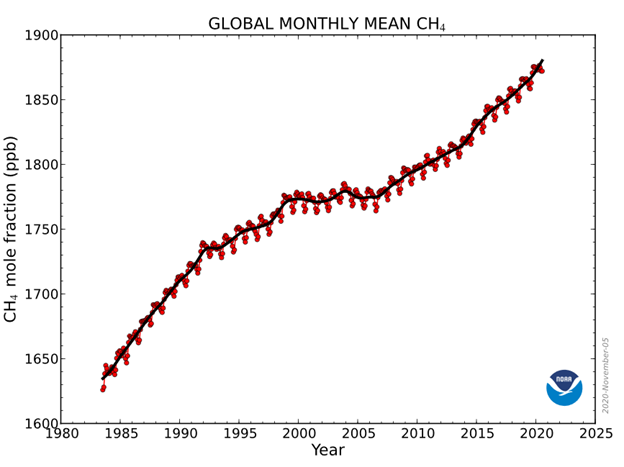

Carbon dioxide, of course, isn’t the only greenhouse gas that’s causing our climate to rapidly warm. Pollution by another powerful greenhouse gas, methane, climbed sharply in 2019, according to the WMO‘s report, continuing a roughly decade-long spike that followed a period of relatively flat methane concentrations from 1999 to 2006.

Methane is the main ingredient in the fossil fuel natural gas and can also be a by-product of the agricultural industry or come from natural sources. When it leaks or is deliberately vented into the atmosphere by the oil and gas industry during drilling, transportation, or refining, methane can warm the climate rapidly. Methane pollution’s warming effects are at their most powerful during the gas’s first 20 years in the atmosphere, when it can warm the climate 86 times as much as carbon dioxide. (Carbon dioxide pollution breaks down more slowly, meaning that its warming effects linger much longer.)

Last year, global methane concentrations increased by 8 parts per billion [ppb], which “continues the trend of the past decade of methane increasing by 5–10 ppb per year,” the WMO noted.

Methane levels in the Earth’s atmosphere have surged since 1980, U.S. federal data also shows. Credit: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)

In 2019, methane levels topped 2.6 times higher than they were in the year 1750, before the dawn of the industrial era, the WMO report notes — meaning that methane has been accumulating even more rapidly than the other two main greenhouse gases, carbon dioxide (1.5 times pre-industrial levels) and nitrous oxide (1.2 times).

The WMO pointed to increased methane emissions both from natural sources like tropical wetlands and human activities “at the mid-latitudes of the northern hemisphere,” such as in the U.S., as the “likely causes of this recent increase.” That would be roughly consistent with peer-reviewed research published in July by Stanford University’s Earth System Science chair Robert Jackson, whose work connected the rise in methane emissions to “emission increases in agriculture, waste, and fossil fuel sectors from southern and southeastern Asia, including China, as well as increases in the fossil fuel sector in the United States.”

Just one U.S. oil field, the Permian Basin, which stretches across West Texas into New Mexico, has driven about 10 percent of the global rise in methane emissions since 2010, Cornell University professor Robert Howarth told Bloomberg in April. “When these sort of emission rates are considered, methane makes the greenhouse gas footprint of natural gas far worse than even that of coal,” Howarth said.

U.S. Oil Production Continues

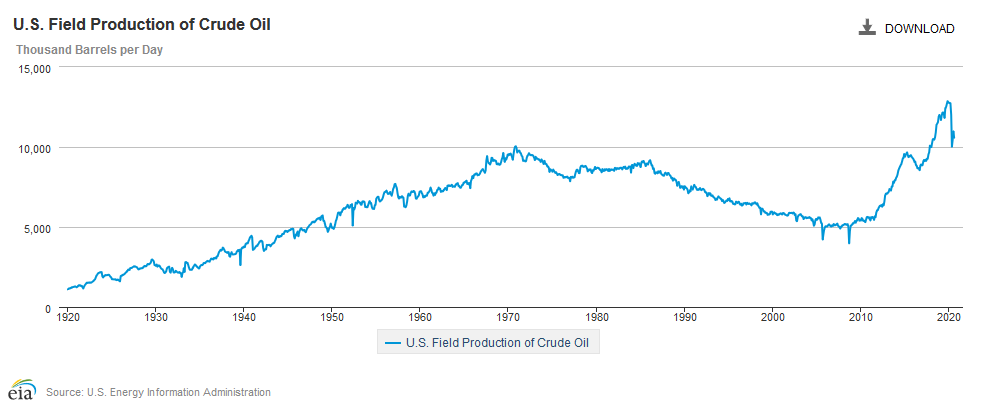

Last year, the U.S. reached staggering new levels of oil production, averaging 12.23 million barrels a day of crude pumped from the ground, according to the Energy Information Administration (EIA). But this spring, as COVID-19 lockdowns and a global oil trade war broke out, oil production dropped sharply from April to May, EIA data shows, falling roughly 2 million barrels a day and remaining in the 10 million barrel–a-day range since.

That’s a sizeable drop — but because the U.S. has had a historic rise in oil production, largely driven by the shale oil boom over the past decade, it also meant that oil production levels in 2020 only dropped to around where they stood at the beginning of 2018.

U.S. production of crude oil from 1920 to 2020. Credit: U.S. Energy Information Administration.

Nonetheless, even as the pandemic caused no significant decline in emissions, oil and gas advocates in the Permian Basin have used the pandemic, and the resulting disruption in oil markets, to argue that now simply isn’t the time to regulate fossil fuels.

In New Mexico, for example, state senator Ron Griggs argued against proposed methane emission regulations that he said had been introduced at a time when the oil industry was bringing in “money hand over fist” for the state — before the pandemic. Now he said, regulation requiring well operators to cut their emissions could make it too expensive for companies to keep oil and gas wells flowing.

The Trump administration has also used the pandemic as a reason to loosen environmental regulations in recent months, and the oil and gas industry has so far received up to $15.2 billion in direct economic relief from pandemic stimulus programs.

All of this at a time when reports such as the WMO‘s show that globe-warming emissions are continuing to rise, despite any hit to fuel consumption the pandemic may have had — making climate action more urgent than ever. “We need a sustained flattening of the curve,” of greenhouse gas pollution, the WMO’s Taalas said. “There is no time to lose.”

Main image: Kings Langley High Street in the UK at 8:00 a.m. on April 5, 2020, amid COVID-19 lockdowns. Credit: Cpettit2007, Public DomainSubscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts