Dramatic violin music starts up as the viewer is invited to marvel at Earth, spinning on its axis, from some unknown point in outer space. The camera zooms down to ground level to show the buzz of modern civilisation, and a breathy voice tells us: “we understand how important it is to look after our planet”.

So begins a video released last year by DHL in a bid to promote its new “GoGreen” initiative – the latest effort by the logistics giant, whose operations emitted 41,000 tonnes of nitrogen oxide emissions in 2019, to highlight its engagement with environmental issues.

Adverts boasting of companies’ green credentials are now a familiar sight, as firms strive to reassure an increasingly concerned public. At the same time, however, many remain members or funders of lobby groups working to delay or water down clean air measures in cities across the UK, a new investigation by DeSmog UK reveals.

These arm’s-length trade associations and campaign groups have an estimated combined annual revenue of £130 million and enjoy high-level political access. Their lobbying results in weakened air quality measures while leaving their members’ environmentally-friendly reputations untarnished.

Find more information on the lobby groups in DeSmog’s Air Pollution Lobbying Database

Click on the circles and lines for information about the lobby groups, companies and politicians featured in this investigation.

‘Invisible killer’

Air pollution has risen up the political agenda in recent years, as studies link it to a range of health conditions, including lung cancer, asthma and heart disease.

A landmark report jointly published in 2016 by the Royal College of Physicians and the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health found poor air quality could be contributing to as many as 40,000 early deaths per year in the UK and causing more than £20 billion in annual costs.

The issue has again hit the headlines in response to a fall in traffic caused by government lockdowns, with residents of polluted areas enjoying a taste of clean air for the first time. Research by the British Lung Foundation found as many as two million asthma sufferers were experiencing reduced symptoms, though pollution levels in cities have been rebounding as lockdown measures ease.

There is also increasingly compelling evidence that poor air quality may increase the rate of death and infection from COVID-19, prompting clean air campaigners to launch a legal challenge in September after the government refused to review its air quality strategy in the wake of these findings. A recent study also found high levels of air pollution could be partly responsible for the disproportionate impact of the virus on BAME communities, among other factors.

A parliamentary inquiry is currently looking into whether the government is doing enough to provide the “national leadership necessary” to tackle air pollution.

Because while official figures show technological improvements are leading to a gradual fall in emissions of nitrogen oxides (NOx) and particulate matter (PM), key sources of air pollution, a majority of urban areas in the UK still consistently breach legal limits.

Despite this, the introduction of schemes to cut pollution in the worst-affected UK cities outside of London has now been postponed until at least next year, with proposed Clean Air Zones (CAZs) in Birmingham, Bristol, Leeds, Sheffield and Greater Manchester all delayed. Low emission zones in Aberdeen, Dundee, Edinburgh and Glasgow will not be brought in before 2022.

The roll-out of CAZs follows multiple embarrassing legal defeats for the government in recent years. Schemes which charge the most polluting vehicles to enter them have been described by experts as the most effective way of cutting pollution quickly, with polling commissioned by environmental law charity ClientEarth suggesting strong public support for the measures.

The charity is calling for the schemes to be brought in as soon as possible in the face of delays, highlighting their track record in improving air quality. London’s equivalent of a CAZ, the Ultra Low Emission Zone (ULEZ), contributed to a significant drop in pollution when it came into force last year, according to Transport for London.

| Glossary |

| Emissions charging A measure whereby older, more polluting vehicles are required to pay a fee for entering a certain area, usually the centre of a city with particularly poor air quality. Clean Air Zone Low Emission Zone Ultra Low Emission Zone |

Vested interests

The lobbying efforts of a select set of pressure groups and trade associations, representing some of the UK’s most famous brands, appear to have dampened the UK’s clean air ambitions, however.

The 20 groups DeSmog analysed for this investigation vary in terms of their level of opposition and are in some cases supportive of certain policies to cut pollution, while being critical of others. Taken together, though, their actions are slowing the implementation of air quality measures in areas consistently breaking legal emissions limits.

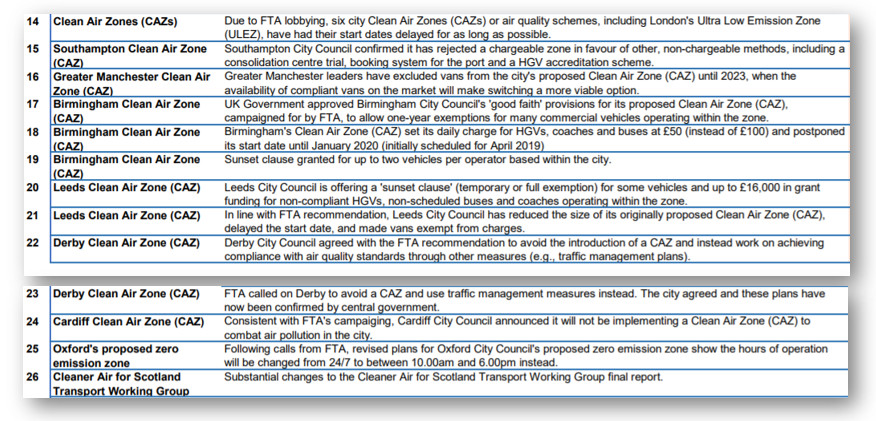

Logistics UK, whose members operate more than half of all lorries in the UK, lists one of its 2019 policy achievements as delaying six Clean Air Zones (CAZ) “for as long as possible”.

Image: Excerpts from a Logistics UK document outlining “policy achievements for members” in 2019.

The group, which argues emissions charging zones place an unfair burden on its members, says that its campaigning has led to cities like Southampton and Cardiff abandoning the schemes in favour of “non-chargeable methods” such as improved traffic management, as well as the exemption of vans from schemes in Greater Manchester and Leeds.

In a briefing for local authorities, the Freight Transport Association, which renamed itself Logistics UK in July, claimed CAZs were “not necessary to deliver improved air quality” and their benefits would be “short-lived”, urging the councils to consider alternatives.

Although Logistics UK told DeSmog it had a “longstanding corporate policy not to disclose details of individual members other than to the authorities for matters of compliance”, Sainsbury’s, Asda and the John Lewis Partnership, which operates John Lewis and Waitrose, confirmed their membership when contacted.

DHL and Hermes, executives of which sit on Logistics UK‘s board of directors, refused to say whether they were members. Other reported members including Tesco, Morrisons, Royal Mail, Greggs and Coca Cola similarly declined to confirm their current membership status.

Asda said it supported the “aim of reducing the impact of logistics on the environment”, while John Lewis referred DeSmog to its recently announced ambition to phase out fossil fuels from the company’s transport fleet by 2030 through the use of biomethane, produced from food waste and other waste materials.

Lobby Groups vs Company Statements (Text)

When contacted by DeSmog, Logistics UK said it was “fully supportive of the need to improve air quality in the UK’s cities” but argued any solution “needs to be proportionate and fair to all”. A spokesperson pointed to its participation in initiatives such as the Low Carbon Vehicle Partnership and Logistics Emissions Reduction Scheme as evidence of its commitment to addressing “the need for new product developments in this area”.

Another trade association representing freight companies, the Road Haulage Association (RHA), has played a similar role in opposing emissions charging zones.

Despite calling for efforts to “bring down harmful nitrogen dioxide emissions”, the RHA’s Policy Director has called CAZs an “anti-business tax grab” and claimed the schemes disproportionately affect Heavy Goods Vehicles (HGVs).

In its 2018 annual report, the organisation claimed it was a “major influencer” in Southampton’s decision not to go ahead with a charging zone and said its “vigorous campaigning” had produced results, with Derby and Nottingham also rejecting the schemes.

The Managing Director of Transport at DHL Supply Chain UK & Ireland sits on the RHA‘s board of directors, and XPO Logistics, Freightlink Europe and Wincanton also confirmed they were members.

Logistics UK and the RHA are both “founding backers” and funders of Fair Fuel UK, a pressure group launched in 2011 that has helped to stave off fuel duty increases by the government ever since. Fair Fuel states on its website that “emotive and dubious air quality claims” are causing vehicles to lose resale value and rejects emissions charging zones as being “based on flawed health data”.

When asked about these positions, Logistics UK said its work with Fair Fuel “centres on fuel taxation and its imposition” and it could not comment on its other policies.

In 2018, the two trade associations joined forces with the National Franchised Dealers Association (NFDA) and the British Vehicle Rental & Leasing Association (BVRLA), whose members are responsible for a “fleet of over five million cars, vans and trucks on UK roads”, to push back against planned CAZs.

The coalition argues that imposing emissions charges on older lorries will increase the number of vans in use, worsening congestion and pollution, and claims the haulage industry has already cut its nitrogen oxide emissions significantly, with research by the RHA showing a reduction of over half since 2013.

In a factsheet about the impact of CAZs on HGVs, the trade bodies argued that charging zones should only be used “where absolutely necessary” and should be “as small as possible”.

Both Logistics UK and the BVRLA, which also previously funded Fair Fuel, welcomed the postponement of CAZs announced by the government at the beginning of the coronavirus pandemic. Logistics UK called for a planned strengthening of emissions standards in London’s existing Low Emission Zone (LEZ) to be delayed, while the RHA welcomed the suspension of London’s LEZ and ULEZ, which have since been reinstated.

Like what you’re reading? Support DeSmog by becoming a Patron today!

Chris Ashley, RHA’s Head of Policy on the Environment and Regulation, told DeSmog the organisation “absolutely supports the aim to improve air quality” but said “faulty” policies had “distorted vehicle replacement cycles”. He called on the government to “re-design and phase-in CAZ standards so that we can play our part in promoting a sustainable, healthy environment that supports jobs and growth”.

An RHA spokesperson added that the industry had been left feeling “attacked”, with the second-hand value of their vehicles disappearing and a “patchwork” of different schemes creating further difficulties.

A BVRLA spokesperson said the wide range of different proposals made the government’s clean air plans difficult to keep track of. It told DeSmog it supports the overall goal of reducing air pollution, but “continues to call for a consistent approach, clear communication and clarity of rules and charges to avoid confusion as drivers and fleet operators move between regional boundaries.”

It also called on local authorities considering schemes to learn from existing programmes, and ensure any measures introduced “avoid punishing small businesses, who are already facing hardship because of the impact of the coronavirus.”

The car rental company Enterprise, a member of the BVRLA, told DeSmog it had “worked with transport, combined and local authorities across the UK to support them implementing clean air zones” and said it did not oppose charges for old, “high-polluting vehicles”. XPO Logistics, an RHA member, reiterated its “longstanding commitment to environmental improvement, especially clean air” through the use of modern, cleaner vehicles in its fleet.

Politically connected

Many of the organisations enjoy close ties to – or the support of – leading politicians, including seven current ministers, 11 shadow ministers, and 12 former ministers, with a total of 85 MPs and peers connected to the groups.

Nowhere is this clearer than in the case of the Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders (SMMT), the principal trade association for the UK’s automotive industry, with Jaguar Land Rover, Volkswagen, Ford and Nissan among its over 800 members.

The organisation accepts the “serious risk to health” posed by air pollution and said in its annual Automotive Sustainability Report last year that the industry “recognises the need for continued improvement” on the issue.

But it has also been a staunch defender of diesel vehicles as concerns about their contribution to poor air quality have grown, having urged the government to provide a £1.5 billion scrappage scheme that would encourage drivers to buy new petrol and diesel cars, as well as electric vehicles, in response to the coronavirus pandemic.

In 2015, it launched a public campaign against what it called the “creeping demonisation” of diesel, just months before the “dieselgate” scandal broke, damaging Volkswagen’s reputation and highlighting the discrepancy between official emissions figures and the pollution produced by diesel vehicles in “real-world” conditions. Campaigners at the time accused the SMMT of being misleading by failing to take into account where emissions were being produced, in order to downplay the contribution of road transport to air pollution compared with other sources.

The government is currently considering proposals to ban the sale of new petrol and diesel cars by 2035 or sooner, with oil giants Shell and BP calling for an early phase-out date, in line with many green groups. Car manufacturers have, by contrast, claimed the move will price low-income families out of owning vehicles.

While the SMMT describes air quality as one of the “biggest challenges facing society” and says it supports CAZs as long as they are based on a nationally consistent framework, it has been strongly critical of some schemes. It opposes a ban on diesel cars in Bristol city centre, calling the proposed move “draconian”, and has said it wants to see a “flexible approach to enforcement” under London’s ULEZ for HGV operators planning to upgrade their vehicles.

In a statement, the SMMT’s Chief Executive Mike Hawes said the industry body was committed to pursuing “a zero emission future” for its members but argued that some of the government’s current policies were not the right way to achieve this goal.

“Getting to zero is about market transformation, and a sustainable transition that supports consumers and businesses on the journey will require the full range of powertrains. Proposed blanket bans or penalties, which don’t distinguish between the latest vehicles and decades-old technologies, will cause confusion and undermine fleet renewal, which has already stalled during the coronavirus crisis,” he said.

The SMMT is one of several organisations that enjoy close contact with top decisionmakers in Westminster through All-Party Parliamentary Groups (APPGs). The groups provide a forum for MPs and interested parties to discuss specific policy issues, but have been accused of being a means for businesses to carry out “covert lobbying”.

Boris Johnson’s Chief Business Advisor Andrew Griffith, Chairman of the 1922 Committee of Conservative backbench MPs Sir Graham Brady, former Business Secretary Greg Clark and four members of the shadow cabinet all hold positions within the large All-Party Parliamentary Motor Group, which the SMMT administers.

Griffith said he was “unaware of the SMMT’s policies on this matter” but had been “very supportive of zero emission vehicles”.

The Road Haulage Association similarly pays for the running of the APPG on Road Freight and Logistics, which aims to “promote and represent the interests” of the sector, and is chaired by Conservative MP and former Roads Minister Sir Mike Penning. One of the group’s Officers, Sir Peter Bottomley, is another former Roads Minister, having served under Margaret Thatcher in the 1980s.

Penning told DeSmog it was “vital that we tackle the challenge posed by high levels of air pollution in our towns and cities and CAZs can play an important role in meeting this challenge”. But he said these would be most effective when “focussed on changing behaviour rather than simply penalising haulage companies which are essential to our economic recovery”.

Not all members of the APPGs necessarily support the lobby groups’ positions, and some appear to participate in the APPGs due to the importance of the related sectors in their constituencies.

For instance, the Chair of the SMMT’s All-Party Parliamentary Motor Group, Labour MP Matt Western, also chairs an APPG on Electric Vehicles, which promotes EVs, and last year organised a “Clean Air Summit” in his local constituency of Warwick and Leamington, where Jaguar Land Rover is a major employer.

Western told DeSmog he was calling for the government to introduce a vehicle scrappage scheme to help meet “crucial climate commitments and restart our economy after this crisis”. He said new diesel vehicles “emit a small fraction of carbon compared to older models currently on our roads” but that zero and low emission cars needed to be “well supported so that consumers start the transition to cleaner vehicles”. He also called for more government support for e-bikes, following efforts in France and Germany.

Western is also Vice Chair of the APPG on Small and Micro Business, administered by the Federation of Small Businesses (FSB), which has opposed the planned expansion of London’s ULEZ. When contacted by DeSmog, the FSB said air pollution was “one of the biggest threats to the environment” but argued CAZs could lead to small businesses being “disproportionately impacted, as those who rely on lorries and vans might struggle to foot the cost in a market already suffering because of COVID-19.” It said it would welcome new scrappage schemes to help businesses upgrade their vehicles, but that it “does not believe these schemes alone will be sufficient”.

Western said: “I firmly believe that we must transition to a low emission transport system to clean up our air and save our planet. Making this transition will create legitimate anxieties from businesses about the impact this would have on their trade, especially if they are in town or city centres. A part of this journey must be to ensure small businesses are not negatively impacted from measures to clean up the air.”

The former Green Party leader and peer Natalie Bennett is also an Officer of the APPG while Conservative MP Robert Courts, Parliamentary Private Secretary to Transport Secretary Grant Shapps, chairs the group.

Bennett told DeSmog she believed the FSB‘s policy to oppose the ULEZ expansion was adopted before she joined. She said she planned to ask for it to be “reopened and changed” and reiterated her support for efforts to tackle air pollution including CAZs. She said she was “very proud of the enormous amount of work Greens have done on this issue for well over a decade”, which had “only become more pressing” as potential links between air quality and COVID-19 have emerged.

Pressure groups

Trade associations are not alone in lobbying against measures designed to improve the UK’s air quality. Pressure groups such as the TaxPayers’ Alliance (TPA), an organisation close to numerous Conservative politicians, are also active on the issue.

The TPA is based in the same Westminster building as a number of other economically libertarian, pro-Brexit think tanks and lobby groups at 55 Tufton Street, including the climate science denying Global Warming Policy Foundation, and has campaigned against CAZs in recent years.

The group has organised action days in cities with proposed schemes, including Bath, Bristol, London and Southampton, describing the measures as an “air tax” and an ineffective “stealth tax”.

It also wrote a joint letter to Bath and North East Somerset Council opposing the plans, along with the Road Haulage Association, Fair Fuel UK, and the Alliance of British Drivers.

The TPA has previously received funding from the Midlands Industrial Council (MIC), a long-standing group of Conservative Party donors including Lord Bamford, Chairman of the construction giant JCB, and Lord Edmiston, owner of the car importer IM Group, and has ties to a number of leading figures within the party.

Home Secretary Priti Patel and Health Secretary Matt Hancock have both launched reports for the group, while Foreign Secretary Dominic Raab has previously written articles for the TPA warning about the costs of climate change policies. International Trade Secretary Liz Truss was quoted in its 2019 annual review saying the group was doing “great work” and was a “much needed voice in today’s debate”.

The group’s position is apparently at odds with previous statements made by the ministers on tackling poor air quality. Hancock last year described air pollution as a “slow and deadly poison” and launched a review into its impacts on health, while Truss said she wanted to see increased “focus” on air pollution “at a global level” at an event in 2015 while Environment Secretary.

A spokesperson for IM Group said it was “unable to comment on the affairs of the MIC” but that it “supports the Government’s policies on Clean Air”.

Lord Blackwell, a Conservative peer and Chairman of Lloyds Banking Group, told DeSmog he had had “no involvement with the TaxPayers’ Alliance for many years” and did not support the TPA’s policy as described by DeSmog.

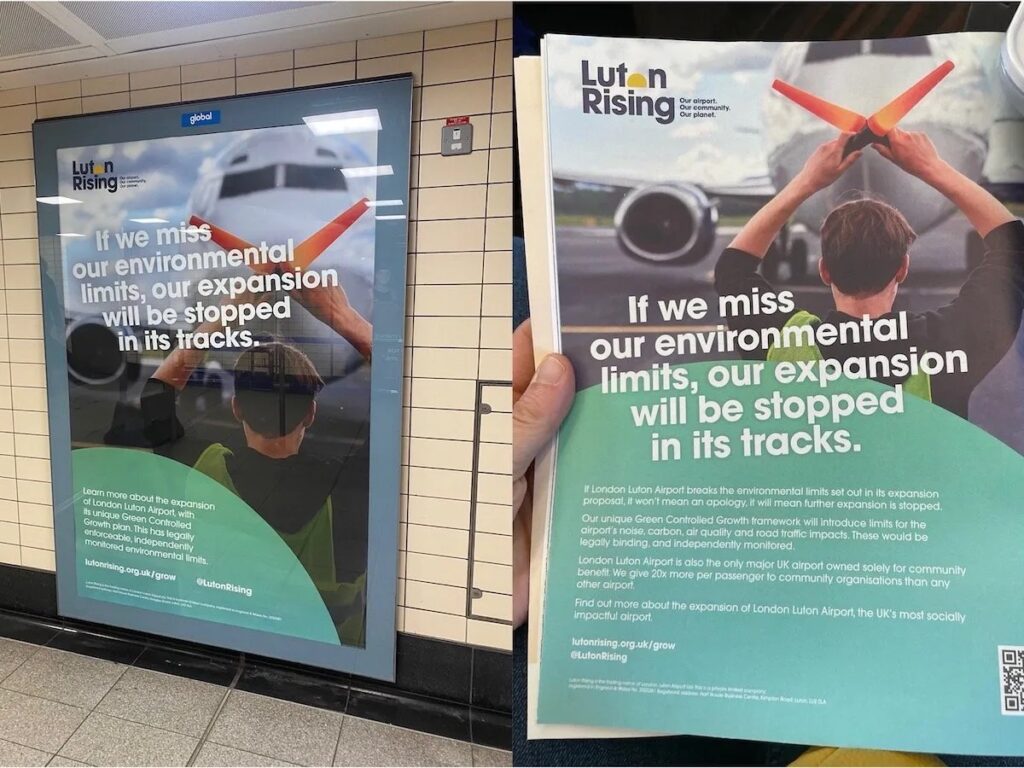

A page from the Taxpayers’ Alliance’s 2019 annual review outlining its air pollution campaigning activities.

The Conservative MP Adam Afriyie, a supporter of the group, said he wanted to see “continued improvements to our environment” and that the “principle of reducing tax on the economic behaviours we want to encourage, and increasing taxes on behaviours we want to discourage, is a good principle.” He said he “values the work and ideas generated by the TPA and other think tanks and lobby groups” but would address specific policies “when they are presented in Parliament”.

Fair Fuel UK has similarly had a close relationship with policymakers through the currently dormant APPG it administered up until the 2019 general election. Chaired by Conservative MP Douglas Ross, its Vice Chairs and Officers included fellow Conservative Robert Halfon, a strong supporter of Fair Fuel since its inception, and the SNP‘s Westminster spokesperson on Energy and Climate Change, Alan Brown.

Not all the MPs in the APPG share Fair Fuel’s views, however. Martyn Day, an SNP MP and a former Vice Chair of the APPG, told DeSmog the group’s position on air pollution seemed “completely bonkers” and that he was “very supportive” of low emission zones in principle.

Labour MP Mary Glindon, another former Vice Chair, said she did not believe any member of the APPG would agree with Fair Fuel co-founder and former Top Gear presenter Quentin Willson’s position on air pollution. She told DeSmog she shared the “views of the Labour Party on air quality” and criticised the government for not including World Health Organisation limits on air pollution in its post-Brexit Environment Bill currently under consideration.

Mass membership motoring organisations

Some of the UK’s most recognisable motoring bodies are also involved in lobbying around air pollution measures.

The AA and RAC, which provide motoring services to a combined membership of 23 million drivers and posted revenue of £1.4 billion last year, have been critical of emissions charging schemes.

On its website, the AA describes air pollution as a “worry for everyone, especially for those who live in urban areas or suffer from conditions like asthma”. But in 2017 the motoring organisation welcomed the government’s recommendation that CAZs should be a “policy of last resort”.

In February, a spokesperson for the group claimed a planned CAZ in Birmingham would “discriminate against people who are less able to buy replacement vehicles”. And the group has called the expansion of London’s ULEZ a “radical step” that would cause businesses to struggle.

While the AA has spoken positively about the transition to electric vehicles (EVs), it has also criticised what it calls the “demonisation” of diesel. In response to the proposed ban on diesel cars in Bristol city centre, the AA argued that ambulances, fire engines, buses and other essential services all relied on the fuel, despite these not being covered by the ban.

Although the latest diesel models are cleaner than older versions, they have been shown to break emissions standards when tested in real-world conditions.

An AA spokesperson told DeSmog the organisation was not opposed to CAZs if schemes had been subject to a thorough evaluation process but said the measures weren’t a “silver bullet”. He said they could create “unintended and adverse results on air quality issues” by diverting traffic elsewhere and called on the government to give more support to residents facing the charges.

A Department for Transport spokesperson told DeSmog it was providing £800 million in “funding and expert support” to help local authorities develop clean air plans but that it was for individual authorities to decide “whether or not the introduction of a Clean Air Zone best meets their local needs”.

Like the AA, the RAC also warns of the risks posed by poor air quality, stating that “long-term repeated exposure to diesel exhaust fumes” may increase the risk of lung cancer.

But when the government’s initial air quality plans were published in 2017, the RAC’s Chief Engineer David Bizley said it was “deeply worrying” that charging zones could be introduced that would “affect owners of relatively new diesel and some petrol vehicles”. Like the AA, the RAC has criticised the expansion of London’s ULEZ, arguing that there wasn’t “adequate evidence to justify such an increase” in response to a consultation on the policy.

When contacted by DeSmog, a spokesperson stressed that “these are complex, often nuanced issues” but maintained that Clean Air Zones should “only be introduced as a matter of last resort” and that the merits of one-off charges under London’s ULEZ “remain debatable”, suggesting “road user charging” could be a fairer approach.

“Our position on emissions has evolved over time as more evidence indicates the impact of vehicle emissions on health and climate. We believe that it is absolutely right that the motoring sector reduces its emissions footprint and will continue to welcome Government initiatives which encourage cleaner driving,” the spokesperson said.

The RAC previously helped to fund the anti-fuel duty Fair Fuel UK campaign but told DeSmog it terminated its relationship with the group “around four years ago” after it found its views “were not always aligned”.

The Alliance of British Drivers (ABD), a motoring pressure group with a much smaller membership than the AA or RAC, is arguably the most bullish in its opposition to clean air measures, among the groups analysed. Its website states it is “unclear” whether nitrogen dioxide (NO2) “actually has any negative health impacts” and its Director Paul Biggs has claimed the issue is being used to justify higher taxes “in the guise of clean air zones (CAZ)”.

Air pollution lobby group letter to councillors (Text)

When contacted by DeSmog, Biggs said he did not remember saying nitrogen dioxide was not a public health problem, but stood by his position that the link between the pollution source and mortality was uncertain. He reiterated the ABD‘s view that the London ULEZ and CAZs “simply aren’t cost effective” solutions to air pollution.

The group, which is frequently quoted in the media as an opposing voice to what it calls “anti-car” policies, recently drew criticism for echoing far-right conspiracy theories around COVID-19. It tweeted that the UN, World Health Organisation and World Bank had been “captured by One World Global Marxist sympathisers” aiming to “gradually pauperise and depopulate the West”. The tweet was quickly taken down.

The ABD also recently claimed UK efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions would have “negligible impact” globally and said “many people do not accept” that carbon dioxide is a major cause of climate change.

Not just cars

Taxi and motorcycle organisations have also played a role in campaigning against clean air measures.

Although the Licensed Taxi Drivers’ Association (LTDA), which represents black cab drivers in London, said it welcomed plans for the ULEZ in 2016, it then lobbied successfully for licensed taxis to be exempt from any charges under the scheme because of the accessibility they provide to wheelchair users.

The LTDA has also been strongly critical of more localised efforts to reduce traffic, calling a proposed ban on taxis, cars and lorries using the busy Tottenham Court Road during daytime hours a “throwback to some 1960s pedestrian utopia”.

The group’s General Secretary Steve McNamara claimed in the group’s in-house Taxi magazine in February that the trade’s contribution to air pollution was “debatable” but has nevertheless been supportive of the move to electric taxis, predicting in 2017 that diesel taxis would be “a thing of the past” by 2023.

The LTDA also opposes a planned charge on drivers accessing Heathrow airport as a means of cutting illegal levels of air pollution around the airport, working in a coalition of taxi groups including the London Cab Drivers Club and the United Cabbies Group, and the Unite and RMT unions.

Cover and first page of the LTDA‘s in-house Taxi magazine, leading on a feature campaigning against the Heathrow levy.

The LTDA jointly funds the APPG on Taxis, which exists to “support and promote the interests of the taxi trade in parliament”. Chaired by Labour MP and Shadow Treasury Minister Wes Streeting, its members include one former transport minister, one treasury minister and six shadow ministers. Among other activities, the group, which is also part-funded by the London Electric Vehicle Company, works to support the take-up of electric taxis.

When contacted by DeSmog, the LTDA said its drivers “understand only too well the need for action to address London’s toxic air that they breathe every day”, and said the taxi trade had invested over £200 million in Zero Emission Capable (ZEC) vehicles, which new London taxis are now required to be.

A Transport for London (TfL) spokesperson told DeSmog its decision to reduce the current age limit on taxis, a measure designed to accelerate the replacement of more polluting vehicles that the LTDA has opposed, was an alternative to including taxis in the charging scheme, in addition to mandating new taxis to be ZEC.

The British Motorcyclists Federation (BMF) and the Motorcycle Action Group (MAG), whose Director of Communications and Public Affairs is former Liberal Democrat MP Lembit Opik, both argue that motorcycles should also be exempt from charges under the London ULEZ. The Motorcycle Industry Association (MCIA) believes the charge should be lower for motorcycles because they are currently subject to the same level of charge as a more polluting four-wheel drive vehicle.

The groups say “powered two-wheelers”, a vehicle category including motorcycles and scooters, should be actively encouraged as a means of cutting congestion and pollution.

The MCIA also claimed many vehicles were being charged despite not breaching emissions limits, forcing owners to pay for their vehicles to be tested in order to prove compliance. It criticised TfL for not working with them on this issue, which it said had a particular impact on low-income Londoners. It told DeSmog it was against the “disproportionate nature of the scheme”, not the scheme itself. MAG likewise told DeSmog it “fully supports effective policies to improve air quality” but that it “does not believe that charging Clean Air Zones are the best way to tackle the issue.”

A TfL spokesperson said the issue of some owners needing to test their vehicles was common to all vehicle types and highlighted the Mayor of London’s scrappage scheme to help “low income and disabled Londoners” scrap their motorcycles for cleaner vehicles.

He also said that while the comparatively small number of motorcycles in the city account for a small proportion of overall air pollution, individual motorcycles can contribute significant amounts.

‘Disproportionate political influence’

DeSmog’s findings have been met with concern by clean air campaigners and academics working on the issue.

“This research raises some worrying questions. Air pollution is a serious public health issue and tackling it is essential for the health of people in towns and cities across the country. Anything that slows or even blocks those efforts is an unwelcome distraction from action to protect people’s health,” Andrea Lee, Clean Air Campaigns and Policy Manager at ClientEarth, said.

“Strong policies to tackle illegal and harmful air pollution will also provide industry with certainty as to the direction of travel, helping to drive action and make the UK a world leader in clean technologies with a resilient, thriving and inclusive economy,” she added.

Professor Stephen Holgate, Clinical Professor of Immunopharmacology at the University of Southampton and special adviser on air quality at the Royal College of Physicians, said while it was difficult to say what impact the lobbying was having, he suspected the groups’ influence was “greater than we all realise”.

“There’s a fine line between deliberately obstructing on the one hand, and stimulating an arguably legitimate debate over timescales of implementation and the economic implications of proposed policies. In a capitalist democracy there has to be a consideration of the economic issues as well as the public health ones and the more ‘responsible’ businesses will enter into this debate in a rational and constructive way. These businesses will inevitably seek to minimise the financial burden on themselves and will seek to ensure what they consider to be adequate timescales for implementation,” Holgate, who has called for the UK to adopt a new Clean Air Act, said.

“Businesses can be very clever in citing the above arguments on the one hand, or attacking the pollution and health evidence on the other, particularly where their businesses are threatened,” he added.

Greg Archer, UK Director of Transport & Environment, pointed to a poll recently commissioned by his organisation which found strong support for Zero Emission Zones among city residents. But he argued a “vocal minority of business and extremist groups are making sure they are heard over the silent majority.”

“Stalled progress on low emission zones is testament to the disproportionate political influence of these lobbyists. This research lays bare the contradictions and in some cases outright lies of the groups lobbying against the basic human right to healthy air,” he said.

Graphics by Sam Whitham; maps by Zak Derler; edited by Mat Hope.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts