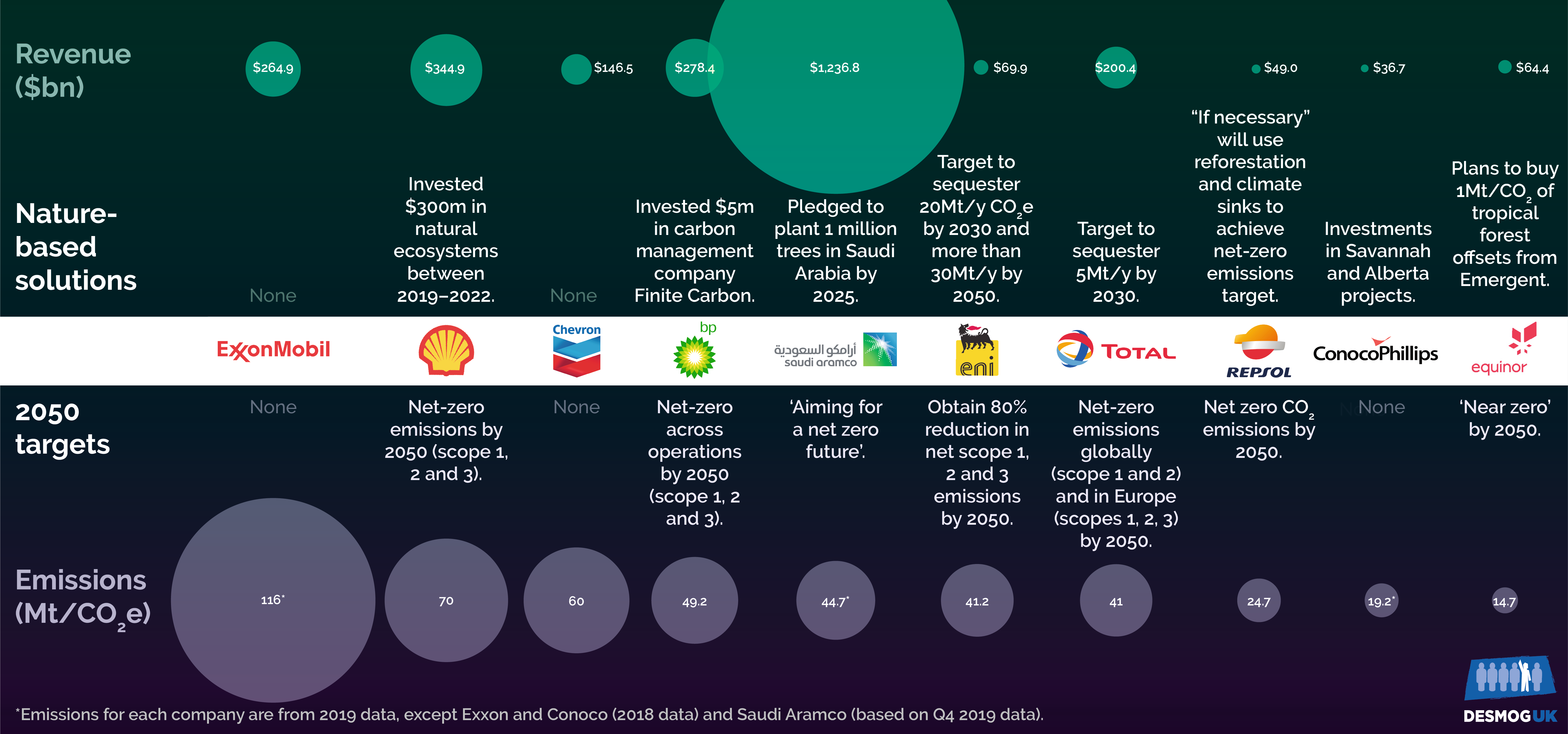

Elon Musk, Greta Thunberg, Rishi Sunak, Donald Trump — trees suddenly have an eclectic mix of fans, all drawn to the apparent simplicity of their carbon-locking power. Now Big Oil has joined the party, in a big way.

Over the past year, BP, Total, Eni, Equinor and ConocoPhillips have invested millions of dollars in forest projects to offset their greenhouse gas emissions. Shell, in particular, has taken a lead, promising to spend $300 million on “natural ecosystems” as part of its market-leading net-zero emissions plan.

The recent surge in corporate pledges gives the impression that nature-based solutions (NBS) provide the key to a decarbonised future. But given oil companies’ status as some of the world’s largest emitters, and the industry’s long history of lobbying against climate action, Big Oil’s push for more trees has been met with scepticism.

There is little doubt that planting trees — often cited as a cheaper and more readily available complement to carbon capture technology — must form part of the solution to climate change. But are trees really the answer to Big Oil’s climate conundrum? Or are schemes that rely on preserving and planting millions, billions or trillions of trees (depending on who you ask) just an excuse to continue drilling for more fossil fuels?

A close inspection suggests that as the projects and regulations currently stand, the trees that Big Oil plans to plant simply can’t live up to the hype. Planting trees may be part of the solution, but not at the expense of widespread systemic change in the energy sector.

This investigation reveals:

- The details of Big Oil’s tree planting plans, and the NGO partners they are cooperating with;

- How Shell has been gaming the voluntary carbon credit market, claiming credits that may be double counted, or that may not qualify to be counted towards their climate goals;

- How renewed interest in nature-based projects has reignited debates around the effectiveness of forestry projects to reduce global emissions;

- And how national agencies, including the Dutch Forestry Commission (Staatsbosbeheer) and Forestry and Land Scotland (FLS) continue to partner with Shell, despite concerns they are helping the company greenwash its image.

Like what you’re reading? Support DeSmog by becoming a patron today!

Investing in nature

Nature-based solutions (NBS) can be anything that involves the use of the natural world — such as forests, grasslands and wetlands — to remove harmful emissions from the atmosphere. The creation and preservation of these lands is enabled by big polluters purchasing credits to offset their emissions.

Corporations’ forest offset fever was in part sparked by the 2015 Paris Agreement, the global climate treaty that committed nations to curbing warming to at most 2°C above pre-industrial levels. The agreement made clear that natural carbon sinks would be vital for countries to hit the goal.

Alongside the Paris Agreement, a joint study co-authored by NGO The Nature Conservancy (TNC) in 2017 was particularly influential in shaping the NBS narrative. It claimed natural solutions could mitigate 37 percent of emissions (or 11 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide) by 2030 to reduce warming to well below 2°C. The report is frequently cited by corporate-friendly global organisations, from the World Economic Forum (WEF) to the World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD).

But the TNC study came under fire from critics of projects that fall under the umbrella of ‘Redd+’ (reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation, plus conservation). They claimed that it ignored the major social and environmental implications of such extensive land use, and is fundamentally infeasible.

Such concerns did little to stem the rising popularity of nature offsets, however, which is most evident in the recent upswing of the voluntary credits market.

Between 2016-2018, sales of Forestry and Land Use (FALU) and Redd+ offsets soared by 264 percent — compared to a 21 percent increase in all other categories. Airlines and oil companies have helped fuel this trend, according to the report by EcoSystem Marketplace (ESM), which singles out the “emergence of major voluntary buyers, such as Shell”.

Significantly, in the past year, Shell, BP and Total updated their climate plans to include ‘Scope 3’ emissions — a major shift.

Historically, polluters have only reported output from their own operations (Scope 1) and from the electricity purchased and used by the company (Scope 2). But these two categories account for just five to 10 percent of emissions. Scope 3, however, includes all harmful gases from fossil fuel products sold to customers.

Without a rapid transition away from fossil fuels, these energy companies will have to rely heavily on carbon offsets to fulfil these expanded targets. That’s where forests come in.

Big Oil investments

Many of the NGOs that partner with Big Oil to deliver the companies’ much-needed forest projects say the corporate partnerships are vital to provide the necessary investment for nature-based emissions programmes. The projects cost money and Big Oil has it, the argument goes.

But these investments should be treated with extreme caution, and only be accepted once all other avenues have been explored, campaigners argue.

TNC, which works with Shell and a number of other corporations on climate strategies, told DeSmog, “many of these nature-based solutions are available for support and investment now, but there is not enough public investment.”.

“Big businesses have an opportunity to scale these environmental benefits on a global scale,”, a spokesperson said, though they acknowledges this must be “with dual investment in natural climate solutions and through ambitious and immediate changes in energy systems, transportation and other activities.”

© Sam Witham/DeSmog UK

Big Oil has certainly suddenly become committed to the NBS cause.

A long-term Redd+ investor, Shell appears to be going further in how it presents its natural climate solutions to the public than any other company. Shell’s newly updated 1.5°C climate strategy – to be fully mapped out later this year – will rely heavily on NBS, following last year’s $300 million investment in natural ecosystems.

Meanwhile, rival BP has donated $5m to US carbon company Finite Carbon to generate its own voluntary carbon market for businesses. BP, which has also previously invested in Redd+ projects, is also set to unveil its net-zero plans in late-2020.

Of all the oil majors, Italian giant Eni appears the most committed to the traditional Redd+ model, with investments planned in Zambia, Mozambique, Ghana, Angola, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Vietnam and Mexico. To help reduce the energy intensity of its products by 80 percent by 2050, Eni plans to store 20 million tonnes per year of carbon dioxide equivalent in forests and wetlands by 2030.

France’s Total has also launched a new fund to invest $100 million a year in NBS, but has estimated these will provide only five million tonnes per year in greenhouse gas reductions by 2030 – just 12 percent of its current Scope 1 emissions.

Taking a different approach, state-owned Equinor in Norway has indicated it is “readying” itself to buy the equivalent of one million tonnes of carbon dioxide per year from Emergent, a “catalyst” that claims it is “priming the market pump that will drive capital toward forest protection on a global scale”.

Norway has long invested in Redd+ projects to offset carbon from its North Sea oil cash cow. But Equinor’s move signals that companies increasingly have an interest in controlling how future offsets are processed.

In contrast, Spanish major Repsol is focusing on investing in carbon capture and storage technology (CCS) — an expensive technology that has been around for decades but is yet to be proven at-scale, and which campaigners regularly reference as a false solution to climate change — to meet its ambitious 2050 net zero target. Repsol has indicated it would additionally offset emissions through reforestation and other natural climate sinks “if necessary”.

European majors’ pledges are far more significant than their US and international counterparts, where NBS barely register in investor reports.

Spokespeople for ExxonMobil and Chevron told DeSmog they had no current plans to invest in NBS, with both companies heavily funding CCS to attempt to align with the Paris Agreement’s goals. Meanwhile, Saudi Aramco, the biggest fossil fuel polluter in the world, announced the planting of one million trees at home, but has not clarified whether these will go towards creating offsets.

Read more: Big Oil’s ‘Natural Climate Solutions’ Feasibility Overblown, Critics Say

Tracey Cameron from sustainability NGO Ceres, which works with the world’s biggest polluters to cut emissions through the Climate Action 100+ initiative, says a nuanced approach is important when it comes to using nature for offsetting.

“NBS should definitely be part of the solution. It should be thoughtful, but also judicious in where it’s used,” she told DeSmog.

However, “it should be used in those areas where there are no alternatives, or where the final mile can’t be hit. It’s part of the strategy but not the strategy. That has to be that the fundamental business has to change,” she argues.

Right now, there’s little evidence that fundamental business model is shifting. Big Oil’s NBS investments are tiny when compared to their fossil fuel business.

Before the coronavirus pandemic, Shell alone planned more than 35 new oil and gas projects by 2025. And the company invested just £2 billion in renewables last year, compared to £30 billion in oil and gas.

So far Total and Eni are the only companies to have declared their nature-based targets in full. Together these equate to just 25 million tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent by 2030, only 60 percent of their respective Scope 1 emissions, and less than half of Shell’s.

New pastures

Shell more than any other has leapt at the possibility of forestry offsets helping it meet its ambitious climate targets. While continuing to buy credits from tropical forests in Peru and Indonesia, Shell is the first energy company to explore creating carbon credits within Europe.

Its $300 million investment in “natural ecosystems” includes two forestry projects in Spain and the Netherlands. The projects highlight a key problem with the current system — it is still unclear who gets credit for the emissions offsets created by forestry projects (or even who can legally claim them).

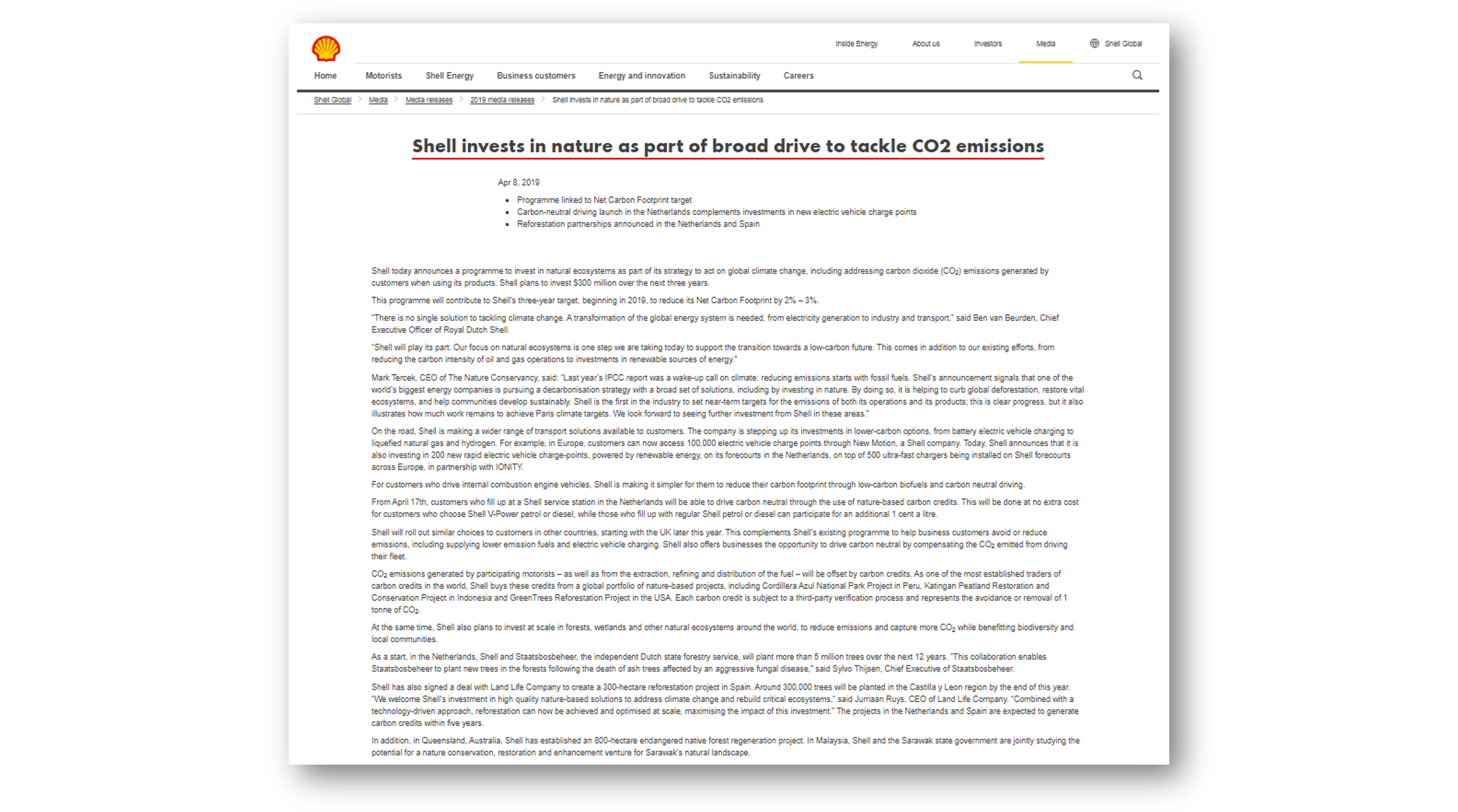

In 2019, Shell paid the Dutch Forestry Commission (Staatsbosbeheer) €17.4 million to plant five million trees over the next 12 years, in areas where an aggressive fungal disease had destroyed the ash tree population. Shell’s press release clearly stated that both projects are “expected to generate carbon credits within five years”.

This appears to be speculation, however, as a Dutch Forestry Commission spokesman acknowledged that the plan was “a work in progress and credits are not yet possible”. That’s because the EU’s Land Use, Land Use Change and Forestry (LULUCF) regulation means all emissions savings from forestry and land use (FALU) projects in the EU are channelled into meeting national climate targets (NDCs), and cannot be counted towards corporate goals.

The EU regulation has been implemented since the Kyoto Protocol (first adopted in 1997), but will be enshrined into national targets under the Paris Agreement from next year until 2030 — making Shell’s initial promise to generate credits by 2024 implausible.

Image: Shell press release, April 2019

Defending the European schemes, a Shell spokesperson told DeSmog that the Staatsbosbeheer was “leading the effort to explore the setup of a potential crediting scheme” under a version of the Green Deal, which supports setting up a voluntary standard for forest carbon projects in the Netherlands.

“Shell is closely following this development, in partnership with Staatsbosbeheer, and any potential credit from the project would follow all requirements and guidance from this Green Deal,” they added.

But Kelsey Perlman, a forest and climate campaigner at NGO Fern, told DeSmog that “creating an offsetting scheme would raise huge questions on compatibility with existing laws and be a terrible step backwards for a country that presents itself as a climate leader.”

That’s because if Shell’s projects go towards reducing emissions under the Netherlands’ national targets, this raises the risk that those savings could be counted twice — towards both the national goal and Shell’s own target.

“There is no way of separating out individual tree planting projects and so to sell them, when there is a high likelihood that these activities go to fulfilling the regulation, is a likely double counting,” Perlman said. “Not to mention that it would then be used to justify pollution elsewhere, which is the whole reason the regulation was kept separate from other sectors,” she added.

The double-counting issues raised by Shell’s project in the Netherlands are mirrored in its attempt to generate carbon credits in the Spanish region of Castilla y León, where it has paid reforestation company Land Life to plant 300,000 trees over 300 hectares of degraded land.

Land Life CEO Jurriaan Ruys said the trees would “remove over 55,000 tons of CO2 from the atmosphere, increase biodiversity and encourage the return of investment to one of the most beautiful parts of Spain”.

But as an EU state, Spain has a target to reduce emissions from its land-use sector and cannot use voluntary credits to do so, so there is a serious question over whether these emissions would have been avoided anyway without Shell’s involvement.

Gilles Dufrasne, policy officer at non-profit Carbon Market Watch, says that by financing the project, Shell is effectively bankrolling national mitigation efforts.

“This means Spain must now do less to meet its target,” he told DeSmog. “Hence all Shell has done is to finance Spanish forest conservation which the government would otherwise have had to do.”

‘Greenwashing’

There was a good reason the Dutch Forestry Commission accepted Shell’s involvement, and it highlights the difficult position in which many agencies tasked with forest protection around the world find themselves.

In 2012, the Staatsbosbeheer was forced to create its own income after government funding cuts. Since then, the agency has overseen the loss of more forest annually than has been newly planted, and has faced controversy for selling off wood for bio-energy generation.

Simply put, Shell’s $17.4 million cheque got the service out of a financial fix.

But that financial benefit came with a heavy cost, as the Dutch press and public lost confidence in the agency.

A Shell spokesperson defended the collaboration, saying that “addressing a challenge as big as climate change requires a truly collaborative, society-wide approach,” and that the company is “committed to playing our part, by addressing our own emissions and helping customers to reduce theirs.”

But despite Shell’s assurances, the Dutch press were quick to raise concerns about the forestry commission’s decision to team up with Europe’s biggest polluter. “This partnership is crying out for answers,” read an editorial in Dutch newspaper Trouw. “Isn’t Staatsbosbeheer getting tied up in a Shell PR strategy? Whatever will happen next?”

Image: Dutch newspapers criticise the Shell deal and the Staatsbosbeheer’s biomass activities

Marjan Minnesma, CEO of climate charity Urgenda Foundation, argued that if Shell really cared about forests, it could have donated the money without trying to generate carbon credits. She told DeSmog that the offsetting scheme was “a very serious greenwashing project”.

“I do not think that there will be any more trees here because of Shell, though it might be financially beneficial for Staatsbosbeheer to get more funds,” she said.

Similar concerns have been raised about Shell’s involvement in a project in the UK, where Shell paid Forestry and Land Scotland (FLS) £5 million to plant and regenerate one million trees between 2019 and 2024. The 250,000 credits created will go towards offsetting customer emissions as part of Shell’s flagship Drive Carbon Neutral programme.

Pat Snowdon, Head of Economics at Scottish Forestry, defended the project, saying it wouldn’t be economically viable without Shell’s involvement. “The government won’t achieve its targets without the private sector,” he said, “carbon offsets and government targets on net CO2 emissions are inextricably linked. If Shell didn’t fund this particular project, it wouldn’t happen.”

But Dufrasne of Carbon Market Watch described the initiative as “ridiculous”. “It is merely an attempt to let their customers buy a clean conscience by giving them the option to pay a carbon price which is 10 times below the price we need,” he said, “as such, it might actually increase driving and therefore pollution.”

An investigation by Scottish independent investigative journalism outlet The Ferret quoted senior staff at FLS raising fears that the project represented a poor return, with the agency risking helping Shell to greenwash its image through the collaboration.

Jo Ellis, head of planning and environment at FLS, noted in an internal email: “The tiny amount Shell is putting into green initiatives is dwarfed by what it is still spending on investigating new oil and gas reserves.” She also referenced Shell’s efforts regarding “blocking initiatives” to cut emissions as a reason not to partner with the organisation.

FLS Chief Executive, Simon Hodgson, defended its partnership with Shell, telling DeSmog that “everyone – from individuals, to corporations to governments – is acutely aware of the urgent need to reduce carbon emissions and everyone has a role to play in tackling climate change, including the wider business and commercial community. Yet a move to a low carbon economy will not happen overnight and – in what will be a long haul – partnership working is essential.”

“No one has the perfect, complete solution for the whole problem of tackling climate change but there are many smaller steps, including enabling more people and organisations to help us plant more trees in Scotland, that can be taken towards arriving at that solution. This is one of them for Forestry and Land Scotland,” he said.

He added that FLS valued “the free and frank exchange of views amongst staff that allows us to determine the right course of action on this and indeed, on any activity that Forestry and Land Scotland is engaging in. That makes for better decision making and will ensure we engage in the right partnerships at the right time.”

Ineffective

Beyond the ethical and PR concerns, campaigners have long expressed concerns about the environmental effectiveness of the schemes — not least how long it will take some of the trees to absorb drivers’ carbon, and how long the forests may exist.

Projects are deemed successful if they store carbon for around 100 years. But it’s very hard to know who will be assessing the schemes by then. And trees only provide temporary storage for harmful gases. When trees die they decay, releasing the stored carbon dioxide back into the atmosphere. So what happens to the land after the trees come to the end of their natural lives is also a problematic unknown.

Future misuse or destruction of that land could reverse any offsets companies claim today, as the equivalent tonnage in carbon stored in these trees is likely to have been ‘spent’ a long time before this happens — through offsetting programmes such as Shell’s Drive Carbon Neutral initiative.

This is not a new concern. Former director of Rainforest Foundation UK, Simon Counsell, was among a group of environmental NGOs working in tropical forests who wrote to the World Bank in 2017, expressing concern over the role Redd+ was playing in offsetting global emissions.

Counsell, co-founder of environmental watchdog Redd Monitor, laments the “many vested interests throwing money at the projects.”

He told DeSmog: “If you look at hundreds of Redd+ projects, none of them have actually worked.”

“At best what happens is that you stop deforestation in one area but it’s moved somewhere else. You have to protect the projects in perpetuity.”

That doesn’t mean such schemes can never be effective. With better regulation, international agreement on how to count emissions stored in trees, and sufficient oversight, NBS could prove their worth.

As Frances Seymour, a climate expert and fellow at the World Resources Institute, says, ”we’re losing tropical forests and other valuable ecosystems at historic rates … if we don’t mobilise some significant finance to create a value proposition for the governments that host these forests to protect them, a reasonable person could argue that that is the greater risk.”

And there are ways civil society can pressure companies involved in offsetting to improve in other ways, she argues, such as ensuring companies that offset have a clear decarbonisation strategy, tying executive pay to progress on these goals, and not allowing companies that lobby against progressive climate policy an opportunity to offset.

Without these, however, Big Oil’s use of carbon offsets comes “with a large caveat”, says Ceres’ Cameron.

“You want to be sure that offsets aren’t going to help continue business as usual,” she argues. “If you’re just looking at offsetting business as usual and not changing your fundamental business model it’s like eating a sundae on a treadmill.”

In the meantime, Shell and its peers are ploughing ahead with their NBS plans. The Dutch, Spanish and Scottish projects could just be the start for Shell, with the company telling DeSmog it is “actively” seeking out partners for future carbon credit programmes.

Campaigners are concerned that if Shell succeeds in selling such projects as environmentally effective, when it is far from clear that is the case, other major polluters are likely to follow its lead.

Nine de Pater, campaigner and researcher at Friends of the Earth Netherlands, warns that placing trust in Big Oil’s green promises could ultimately be devastating.

She told DeSmog, “Shell’s so-called compensation and nature conservation programmes are meant to give us all the impression that the company is heading in a green direction.” But this is a “clear example of greenwashing,” she argues.

“Shell makes sure the public is distracted from what they are actually doing: continuing their fossil fuel activities as they have always been doing.”

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts