A new study from public health researchers provides the strongest evidence yet that increased exposure to a type of air pollution from tailpipes and smokestacks that’s known as fine particulate matter (PM2.5), or soot, can cause premature death. This peer-reviewed study of air pollution impacts on older Americans suggests that current air quality standards set by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) do not protect public health, and that strengthening the standards could save over 140,000 American lives over a decade.

In praising this study as a “slam dunk,” one former EPA air pollution scientist warned that the Trump EPA, which is trying to maintain the current standards, “ignores it at their peril.”

In April the EPA under the Trump administration proposed a rule declining to strengthen the air quality standards for soot, instead keeping the standard set in 2012, despite warnings from current and former EPA scientists that the outdated standard was inadequate and would result in more Americans dying from air pollution.

This proposed rule was met with backlash from air quality and public health experts but was welcomed by groups representing polluting industries that are major sources of soot pollution. “This is a wise decision to protect our air by retaining the current standard,” Jay Timmons, President and CEO of the National Association of Manufacturers, said in a supporting statement released by the EPA.

PM2.5, commonly known as soot, consists of very tiny particles in the air that, when inhaled, lodge deep inside the lungs and can contribute to respiratory illnesses and other health impacts, both over the short and long-term. Emissions from factories, power plants, industrial facilities, and cars and trucks are all sources of soot pollution. Smoke from wildfires is also a source, but the vast majority of this pollution comes from fossil fuel emissions.

An independent panel of air quality scientists — experts who were supposed to help advise the EPA on air pollution standards but were dismissed by the agency’s political leadership — argued in a paper published June 10 in the New England Journal of Medicine that the current soot standards must be strengthened as a matter of, literally, life and death.

This new study, led by researchers at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and published June 26 in the journal Sciences Advances, bolsters this argument with what the researchers say is “the most comprehensive evidence to date of the link between long-term PM2.5 exposure and mortality.”

The @EPA has proposed retaining current national air quality standards. But, as our new analysis shows, the current standards aren’t protective enough. Check this outhttps://t.co/qrx14HiiDN https://t.co/eMqYMdZ14J @HarvardChanSPH @HarvardCCHANGE @harvard_data @HarvardBiostats

— francesca dominici (@francescadomin8) June 26, 2020

The study was published just ahead of the June 29 deadline for public comments on EPA’s proposed rule to retain the 2012 soot standards. The Harvard and Columbia researchers say they hope the study will inform policy considerations on these standards before a final rule is established.

“The Environmental Protection Agency has proposed retaining current national air quality standards. But, as our new analysis shows, the current standards aren’t protective enough, and strengthening them could save thousands of lives. With the public comment period for the EPA proposal ending on June 29, we hope our results can inform policymakers’ decisions about potentially updating the standards,” study co-author Francesca Dominici said in a news release.

‘Willfully Ignoring Inconvenient Studies’

Current EPA Administrator Andrew Wheeler, a former coal lobbyist, and other EPA officials with ties to the fossil fuel industry appear to be deliberately ignoring the robust science showing links between higher levels of air pollution and health risks, according to a former EPA scientist.

As John Bachmann, former Associate Director for Science/Policy and New Programs in the EPA Office of Air Quality Planning and Standards, told DeSmog, the EPA staff scientists who assessed the air quality data recommended the soot standards be tightened. “So [Wheeler] is ignoring the recommendations of his own staff,” Bachmann said.

Bachmann said he and other experts pointed to epidemiological studies that support the case for strengthening air pollution standards, but Wheeler and the current chair of the Clean Air Scientific Advisory Committee (CASAC), which periodically reassesses the standards, dismissed those studies. According to Bachmann, this “suggests they are in fact willfully ignoring inconvenient studies.”

Like Wheeler, Dr. Tony Cox, the current chair of CASAC, has ties to the fossil fuel industry that produces soot pollution. Cox is a statistician focused on risk assessment who has done consulting work for the oil, gas, and chemical industries. His industry ties include work in service of tobacco giant Phillip Morris and trade associations such as the American Chemistry Council, National Mining Association, and the American Petroleum Institute (API). The American Chemistry Council and API are among the organizations issuing comments supporting EPA’s proposed rule to retain the 2012 soot standards.

Cox has previously dismissed studies showing strong links between air pollution and health risks, arguing that there is not enough proof to show a connection that soot pollution causes, rather than is associated with, documented health impacts.

But the new Harvard and Columbia study, which examined 16 years of data from over 68 million Americans ages 65 and older, specifically included analytical approaches to assess if there is a causal connection.

According to the news release, the researchers “used two traditional statistical approaches as well as three state-of-the-art approaches aimed at teasing out cause and effect.” The latter approaches were meant to address criticisms of existing air quality research particularly from critics such as Cox, who heads the EPA advisory committee tasked with reviewing air pollution regulations.

However, Cox appeared unimpressed. He told DeSmog he found the study and its conclusion “highly misleading” and based on “unverified modeling assumptions,” saying that the data and design “do not address effects of interventions” focused on reducing air pollution.

“In general, I believe that paying less attention to imaginary results based on unverified or demonstrably incorrect modeling assumptions such as these, and paying more attention to real-world public health experiences following pollution-reducing interventions in recent decades, provides a better basis for scientifically well-informed policy-making,” said Cox.

“In summary, the latest Harvard paper continues a long tradition of making strong causal claims that turn out to be based on unverified and demonstrably incorrect modeling assumptions,” he added.

But Xiao Wu, a co-author of the study and a biostatistics doctoral student at Harvard, told DeSmog that Cox’s argument “shows he did not read our paper carefully.”

“Our main findings are not based on one model with unverified assumptions. They are based on five different models under different assumptions all producing consistent findings,” Wu explained. “This is only the first step at constructing a causal link. Many other studies under different study designs, model assumptions and study populations found consistent results as well, and importantly, these studies all implemented rigorous scientific methods.”

“Every model or, to an extent, every scientific research, relies on assumptions,” Wu added.

Protecting Vulnerable Populations

The researchers behind this new work on air pollution say their study “provides the most robust and reproducible evidence to date” on the cause-and-effect link between exposure to fine particulate matter (PM2.5) and premature death. The paper concludes “that long-term PM2.5 exposure is causally related to mortality.” According to the study, strengthening the PM2.5 annual standard from 12 micrograms per cubic meter to 10 micrograms per cubic meter would save 143,257 lives in one decade.

“Our new study included the largest-ever dataset of older Americans and used multiple analytical methods … to show that current U.S. standards for PM2.5 concentrations are not protective enough and should be lowered to ensure that vulnerable populations, such as the elderly, are safe,” said Wu.

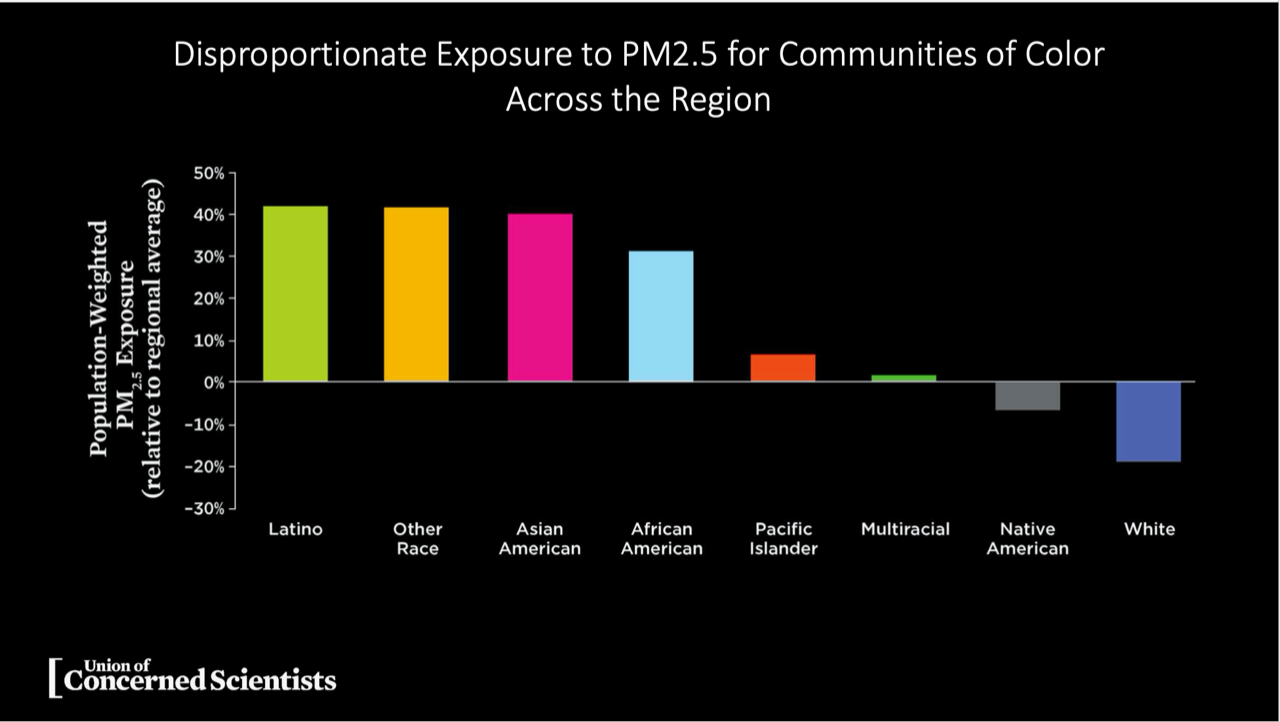

Chart showing disproportionate exposure to PM2.5 for communities of color in the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic region. Credit: Union of Concerned Scientists

Another vulnerable population that is disproportionately impacted by air pollution is communities of color. Research from the Union of Concerned Scientists show that certain ethnic groups like Latinos, Asian Americans, and African Americans, tend to be exposed more often to soot pollution.

“This combined with the results of our newest study implies the mortality rate due to PM2.5 among communities of color will be more severe,” Wu explained in an email to DeSmog.

‘Silver Bullet’ Study

Bachmann, an air pollution expert who worked at EPA for 33 years, said the new study is a rare “silver bullet” that responds to and destroys the main argument for not strengthening the PM2.5 standards.

“It’s a dagger in the heart of the main objection,” he said, referring to the Trump EPA‘s resistence to calls to strengthen the standards. “It’s a slam dunk in a lot of ways, so EPA ignores it at their peril.”

Main image: Salem Harbor Station’s plume spews choking soot into the air in Salem, Massachusetts, in 2009. Credit: Conservation Law Foundation, CC BY–NC–ND 2.0

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts