On May 24, a full-page ad appeared in The Oregonian, Oregon’s largest newspaper. The “open letter,” addressed to Gov. Kate Brown, asked her to support Jordan Cove LNG, a controversial coastal liquefied natural gas (LNG) export terminal. Between the “COVID-19 pandemic and the ensuing economic fallout,” the project would be crucial to restoring the state’s economy, the letter argued. “We’re going to need as many jobs as we can get, and very soon.”

“We ask you to listen because Jordan Cove is about Oregon, but it is also about much more,” the letter said, a statement that certainly seems to describe the entity that bought the ad, the Western States and Tribal Nations Natural Gas Initiative, or WSTN. Despite its sole focus on exporting natural gas through the West Coast, the group is virtually unknown in Oregon.

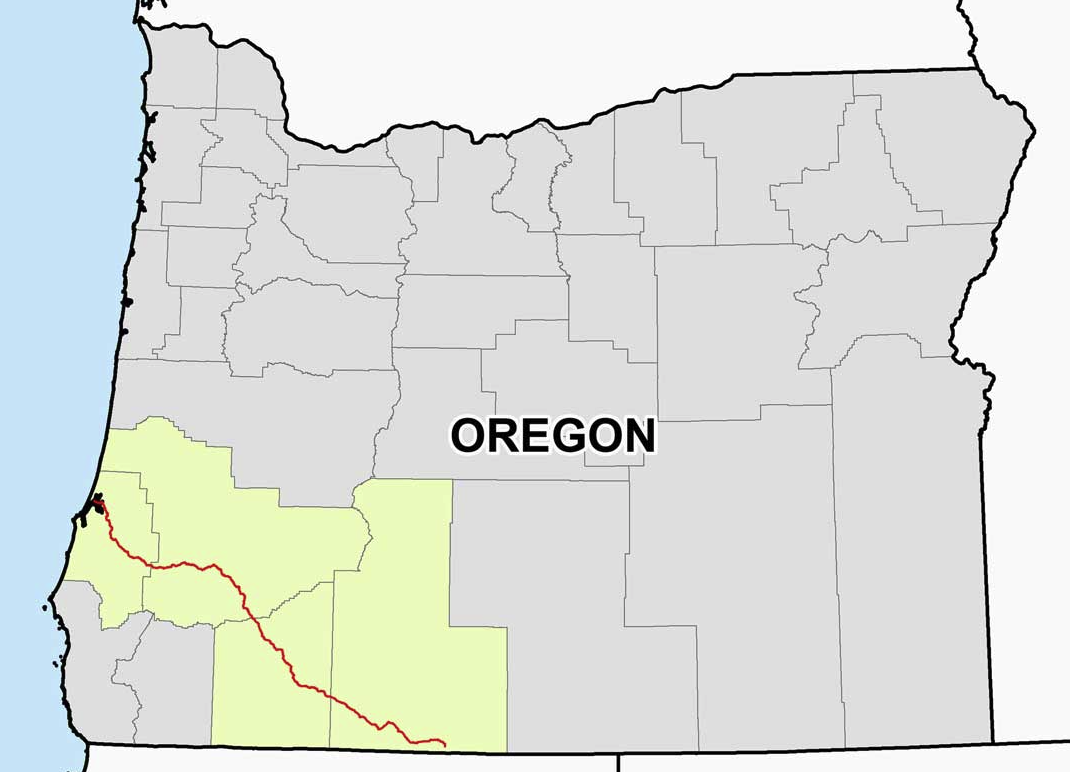

Originally proposed by Canada-based Pembina about 15 years ago, the $10 billion Jordan Cove LNG project consists of a gas export terminal on the southern Oregon coast, connected by a 229-mile pipeline that would extend to Malin, Oregon, where existing pipeline infrastructure runs all the way to the Rocky Mountain region. As envisioned by Pembina, the Jordan Cove terminal and the Pacific Connector pipeline would be capable of exporting 7.8 million tons of liquefied natural gas per year.

WSTN may be stepping into the Oregon fray because Jordan Cove would be the first LNG export terminal on the West Coast, with the potential to open an entirely new Asian market for gas drillers in the inland western U.S.

But the proposal has run into fierce resistance in Oregon as well as a series of legal snags at both the state and federal level. The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) previously denied the project in 2016, but a more industry-friendly Trump era makeup of the commission has revived the project. In March, FERC approved Jordan Cove, and on May 21, denied an appeal to rehear the issue.

In a scathing dissent of the May decision, FERC Commissioner Richard Glick wrote that the approval makes clear that the commission will not allow Jordan Cove’s likely and substantial negative impacts “to get in the way of its outcome-oriented desire to approve the Project.”

Federal regulators uphold approval of Jordan Cove LNG project in Coos Bay, teeing up potential state lawsuit https://t.co/ANsds9Kesq pic.twitter.com/Ek9zd9qLGI

— The Oregonian (@Oregonian) May 22, 2020

The commissioners approving the project failed to grapple with the climate change impacts, Glick noted (it would be Oregon’s largest source of greenhouse gas emissions), as well as failing to account for the threats to endangered species and historic properties, potential noise pollution, and the impacts on short-term housing and landowners in southern Oregon.

“Simply asserting that the Project is in the public interest without any discussion why,” stated Glick, “is not reasoned decision-making.”

The approval incensed Oregon officials as well. “This FERC decision provides fresh and troubling evidence that my concerns about a stacked commission have come to pass,” Oregon Senator Ron Wyden (D) said in a statement, “resulting in arbitrary and awful decisions being dictated from on high about this project.”

But despite FERC’s green light, the obstacles in Oregon appear more difficult than ever for Jordan Cove. The Oregon Department of Environmental Quality denied the project a critical water permit in May 2019, and in January, the project itself withdrew a separate permit from the Department of State Lands before a negative decision could be made.

“This is not just one regulatory agency with one little outstanding concern. This is what looks like a pretty systematic rejection by the state of the project,” Eric de Place, director of Thin Green Line at Sightline Institute, told DeSmog.

But FERC’s decision does grant Pembina the ability to start using eminent domain to seize land in southern Oregon for construction of the gas pipeline, a point Glick emphasized in his dissent: “[I]t would be unconscionable for this Commission to permit a developer to seize private land for a project that has little chance of ever being completed.”

Who’s Behind the Western States and Tribal Nations Natural Gas Initiative?

The genesis of WSTN dates back to 2017 when, following an energy industry conference in Utah, the Colorado Energy Office and the Utah Office of Energy Development formed a group to expand markets for natural gas from those states. The Piceance and Uinta basins of Colorado and Utah sit on enormous quantities of natural gas, but landlocked far inland, they need long-distance pipelines connected to export terminals to move the gas to overseas markets.

That joint effort led to the 2019 publication of a report laying out the case for exporting Rocky Mountain gas to Asia via ports on the Pacific coast.

Credited to “The Research Partnership to Secure Energy for America” and “Mercator Energy,” the report recommended two terminal sites: Coos Bay, a small city on the southern Oregon coast, and Ensenada in the Mexican state of Baja California, about 90 miles south of San Diego.

Then-Colorado Gov. John Hickenlooper supported the proposals (as did then-Utah Gov. Gary Herbert). But in 2019, a new Colorado governor, Jared Polis, withdrew Colorado from WSTN. The initiative carried on with the backing of Utah and Wyoming, as well as multiple county governments in several states and the Ute Tribe of northeastern Utah.

WSTN’s president, Andrew Browning, a partner at Houston-based law firm HBW Resources, is also the chief operating officer of the oil industry trade group Consumer Energy Alliance (CEA). As DeSmog has reported, he is not the only staff that HBW and CEA have in common.

CEA’s members include oil giants like ExxonMobil and BP. Pembina is also a CEA member, although not a member of WSTN.

From the Western States and Tribal Nations Natural Gas Initiative ad in The Oregonian, listing its members who support Jordan Cove LNG. Credit: WSTN

Browning promotes corporate fossil fuel interests when wearing his CEA hat, and promotes the Jordan Cove project on behalf of county governments in the Rockies as president of WSTN. According to WSTN spokesperson Bryson Hull, “CEA and WSTN are separate organizations with separate boards, founded for different purposes and the only connection between the two is the HBW Resources personnel who service both clients.” He added that “any allegations of ‘murky ties’ or that we are ‘quietly’ pushing for LNG terminals on the West Coast are absurd.”

Indeed, WSTN is upfront about promoting Jordan Cove, as its ad in The Oregonian makes clear. Last year, the group brought delegations from Wyoming, Utah, and Colorado to a FERC public hearing in Medford, Oregon, to speak in favor of the proposal. It also coordinated the submission of a wave of public comments by its members to FERC, all supporting Jordan Cove.

This May, speaking as president of WSTN at a virtual meeting of county officials in Sweetwater County, Wyoming, Browning said that “we have jumped in with full partnership with Pembina, which is the owner of Jordan Cove, on their permitting process.”

FERC’s recent support has cleared the way for Jordan Cove at the federal level, “but they’re really getting jammed at the state level,” Browning told the industry-friendly group. Wyoming is a member of WSTN as represented by the Wyoming Pipeline Authority.

WSTN‘s Andrew Browning appears at approximately 2:03:00 in the video.

Referring to the full-page ad in The Oregonian, he said the group was “putting the political heat on Governor Brown…under the vision of the ‘Marshall Plan,’ of New Deal projects, put America back to work, and let this shovel-ready project go.”

WSTN’s spokesperson told DeSmog that Pembina is not a member of WSTN and had no involvement in the ad.

Brook Thompson, a member of the Yurok Tribe, found the ad and the group’s name highly misleading. The Yurok Tribe is located in northwestern California, about 177 miles south of Jordan Cove’s proposed Coos Bay, Oregon site.

The Pacific Connector pipeline “will be crossing through the Klamath River, the river my reservation is based on,” Thompson told DeSmog. The pipeline’s route crosses around 400 waterways and streams in southern Oregon, including the Rogue and Klamath rivers.

“My family has lived on the river for thousands of years and I cannot let a company add risk to my river, my community, and other coastal communities,” Thompson said.

While WSTN claims its founding principles include “tribal self-determination,” Thompson noted that the only tribes WSTN lists as Jordan Cove collaborators are the Ute Indian Tribe of the Uintah and Ouray Reservation, located in Northeastern Utah.

“There are no Oregon or California tribes who have given public support for the Jordan Cove LNG pipeline projects,” she said. “In fact, there are several tribes who have publicly opposed the project or have fought against it through legal action.”

The tribal governments of the Klamath, Karuk, Yurok, and Siletz tribes, as well as the Tolowa Dee-ni Nation, all formally oppose Jordan Cove.

A Failing Business Case for Natural Gas Exports to Asia

Prices for natural gas in Asia began cratering last year amid a growing problem of oversupply. The global pandemic and the collapse of demand have pushed prices down further, with JKM prices (a benchmark for prices in Asia) down below $3 per MMBtu this year.

With this steep downturn, the business logic of carving a 230-mile natural gas pipeline through mountains and rivers to the Pacific coast has begun to fall apart, even after ignoring or discounting its climate and environmental tolls.

Map of the Pacific Connector gas pipeline path through Oregon to the Jordan Cove LNG terminal site in Coos Bay. Credit: Jordan Cove LNG

At current prices, the economics of liquefying American gas and exporting it abroad are “imploding,” according to the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis. As many as 45 shipments of American natural gas were recently canceled by buyers because of the market glut, according to S&P Global Platts.

But Jordan Cove’s other economic headwinds predate the pandemic. Despite the fact that Pembina has pushed Jordan Cove for more than a decade, the project has yet to actually ink a deal with any buyers for its gas, a fact that FERC cited when rejecting the project four years ago. Against that backdrop, Jordan Cove LNG has not demonstrated that it is “needed,” FERC’s Glick said in his May dissent, even though a lack of demand is a factor FERC is supposed to take into account before approving any major project.

WSTN’s Hull disputed the notion that the economic deck is stacked against Jordan Cove. “The LNG industry invests on a decades-long time horizon,” he said, “WSTN’s focus is on Asian markets that will lead global LNG demand growth through 2040.” LNG projects typically operate for decades, so WSTN does not see the current downturn as an insurmountable obstacle.

In March, in response to the pandemic-driven downturn in global commodity markets, Pembina slashed its 2020 budget, roughly halving its original spending plan of $2.3 billion. The company said it would defer some projects, but did not specifically mention Jordan Cove. Pembina did not respond to a request for comment from DeSmog.

Failing in Oregon, Jordan Cove Seeks More Help from the Trump Administration

In May, Pembina’s offices in Klamath Falls and Coos Bay appeared to be visibly empty, according to photos posted to social media by local environmental groups.

Pembina has officially closed up its storefront in Klamath Falls.

Have you seen examples of Jordan Cove LNG fleeing southern Oregon? Send us a message if so!#stopJordanCove #noLNG pic.twitter.com/q5ym9YQrhi

— NO LNG EXPORTS (@nolngexports) May 16, 2020

But Pembina is not giving up on Jordan Cove. Stifled by Oregon regulators, the firm is turning to the federal government to override the state’s authority. “They’ve done a request to the Department of Commerce for an override on the national interest that would circumvent the state’s rejection of their coastal zone management permit,” Browning said at the Wyoming county commissioners’ meeting in May, referring to Pembina. “They’re doing similar efforts to override the rejection of their air and water permits.”

Meanwhile, a coalition of environmental groups, including the Western Environmental Law Center and the Sierra Club, are suing FERC over its approval of Jordan Cove.

Separately, a group of Oregon landowners who would have lands seized by eminent domain for the pipeline is also suing FERC. The group is represented by the Washington, D.C.-based Niskanen Center, a libertarian-leaning think tank founded by a former climate skeptic turned climate action advocate. The lawsuit argues that the damage to land and the environment from Jordan Cove and the Pacific Connector gas pipeline, including seized private property for a pipeline that might not be built, would exceed the public benefits.

“I certainly cannot speak to Pembina’s motivations,” Susan Jane Brown, a staff attorney with the Western Environmental Law Center, told DeSmog. “But my guess is that by packing up their offices and leaving town, Pembina has showed its true colors and lack of interest in the community, and knows that the fight is now in the federal courts.”

Main image: From the Western States and Tribal Nations Natural Gas Initiative ad in The Oregonian, writing an “open letter” of support for Jordan Cove LNG to Gov. Kate Brown. Credit: WSTN

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts