Cancerous lesions have developed across Keith MacDonald’s body and his son is dead from leukemia. His life has disintegrated, and in his eyes fault lies with the third richest company on earth. It is headquartered in the Netherlands, incorporated in the United Kingdom, and is an entity (thanks to the Parliamentary Pension Fund) that every single British MP has a stake in — Royal Dutch Shell.

The story of how MacDonald got here is a tale of adventure and tragedy fit for a Hollywood thriller, only it is real. Even with many unknowns, MacDonald’s case unearths a shocking part of the world’s most powerful industry that somehow has remained hidden for generations.

MacDonald was born on a military base in Scotland in 1951. When he was three years-old, his older brother was killed in a tragic cliff accident—the boy chased a stray football over the edge and fell 100-feet to his death. “My mother couldn’t deal with the stress and became obsessed with my wellbeing,” says MacDonald. “Safety, safety, safety, all of my life. It was almost claustrophobic. I became the family rebel and left home.”

Image: Photos of Keith MacDonald and his brother and mother (left), and their graves (right)

His oilfield story begins in the early 1970s. MacDonald was a rock and roll roadie, setting up equipment for Santana, Elton John, and Rod Stewart — “I was making good money, having a ball.” One autumn day in 1975, he hitched a ride to Birmingham with a friend who had an interview for a job inspecting oil and gas pipelines. The recruitment manager for British Industrial X-Ray wore a shirt and tie, looked MacDonald over and with a string of words that would change the course of his life, offered him a job.

Like what you’re reading? Support independent journalism by donating to DeSmog today!

Into the action

This began a tour of work in some of the world’s most lucrative and remote oil and gas fields, the type of adventurous life that many British men who got into the business in that era can relate to.

“It all happened so quick I couldn’t believe my luck,” says MacDonald. “I was going from peanuts a day to £50 a day, and eventually £5,000 a month.”

MacDonald started on a pipeline in Wales and by 1977 had a job inspecting pipelines as an industrial radiographer in the Libyan oilfields, surrounded by bleached Saharan sands and the hottest temperatures on the planet. A stint in Saudi Arabia followed, then a two-year job in the United Arab Emirates building gas plants where MacDonald was assistant quality assurance superintendent. He spent much of the 1990s in Nigeria, working for Chevron as a senior company representative on a barge that fabricated and upgraded oil rigs. By the late 1990s he was in Oman.

MacDonald is “completely reliable,” one Omani supervisor wrote on a reference form, and has “wide and valuable experience of the inspection and maintenance of oilfield equipment.”

On 13 March 2000, MacDonald celebrated his 49th birthday. Around the same time, he landed in Damascus, Syria, to take a job arranged by the UK oilfield service company, Gray Mackenzie. He would be working for the Al Furat Petroleum Company (AFPC) in the rich Omar oilfield of eastern Syria. It was to be an exciting job, and his first time in the vibrant heart of the Middle East’s oil and gas country, working under one of the world’s storied big majors, Shell.

His penny-pinching days as a roadie were long gone. The constraints of his concerned mother and the cloud of his brother’s accidental death seemed long gone, too.

MacDonald loved his work, and there was an overwhelming sense that he had made it. “You come across people who get up in the morning and are like, ‘Ugh, I got to go to work,’” says MacDonald. “That wasn’t me. I enjoyed every minute of it.”

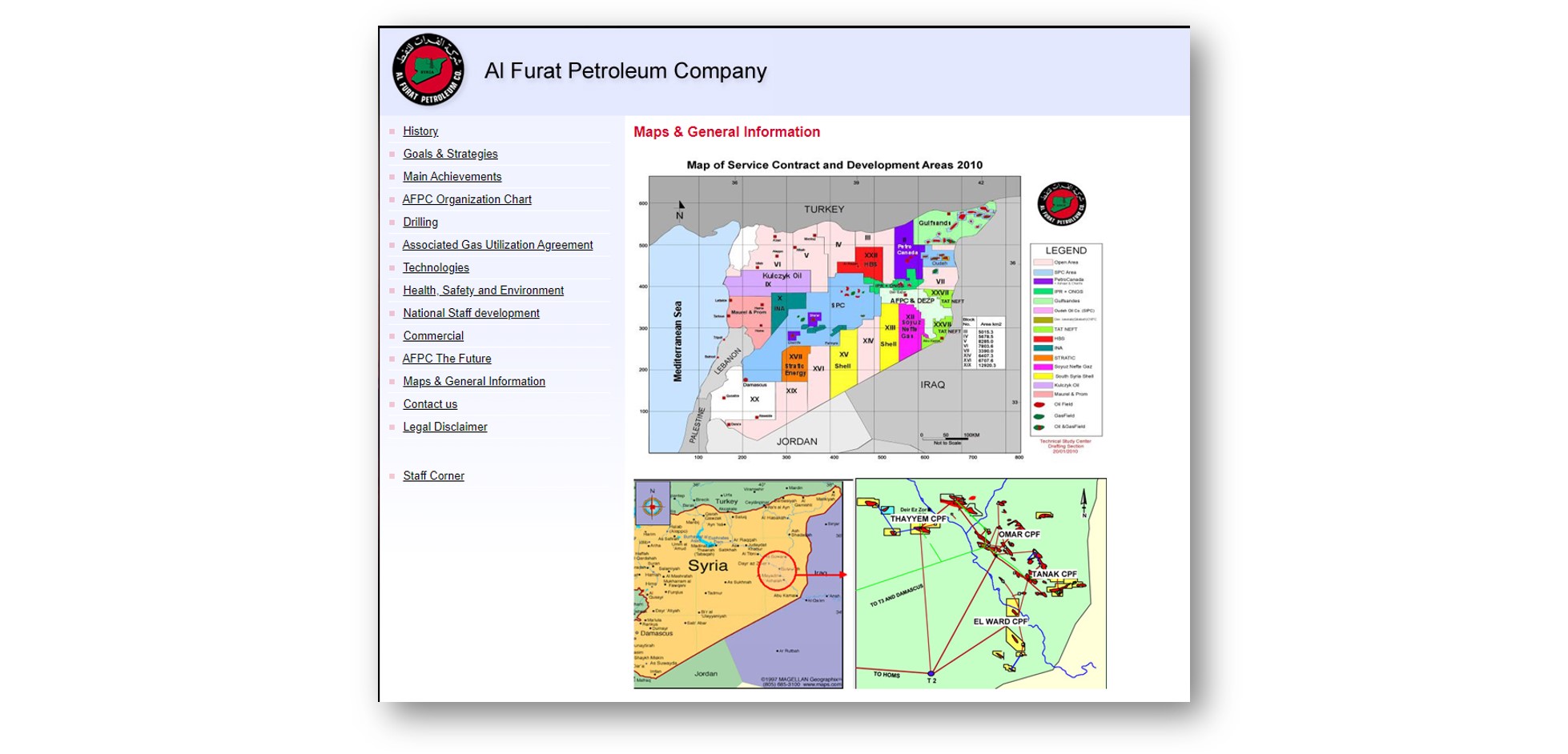

Shell, according to the Wall Street Journal, helped build the Middle East into “a petroleum powerhouse”. AFPC was founded in 1985, a joint venture between the state-owned General Petroleum Corporation, a subsidiary of Shell called Syria Shell Petroleum Development, and other groups. Shell gave the Syrians technology, experts, and technical expertise, according to an AFPC website. A map shows Shell’s various interests in Syria, including the Omar oilfield, not far from the Iraqi border.

Image: Screenshot of the webpage showing maps of Al Furat Petroleum Corporation’s operations.

In 2001, the closest year to MacDonald’s time of work for which Shell’s annual reports are readily available, the company produced 48,000 barrels of oil a day in Syria – at the time just over two percent of their global output. Although Shell left Syria in 2011, as civil war broke out and the European Union imposed sanctions, there is still a record of how the company co-sponsored a festival for “Arab Environment Day,” supported a forum on women leaders, raised money for the blind, and worked with the Ministry of Education to develop lectures for school children about traffic accidents and environmental safety. “We invested more than $8 billion in Syria,” Shell’s general manager for the country, Graham Henley, is quoted as saying.

By the time MacDonald got to Syria, he had worked in oil and gas fields on three continents, but he immediately noticed there was something different about the Omar field. “Wellheads were blocked off with barbed wire fence that prevented anyone from getting close,” recalls MacDonald. “There was yellow caution tape on each side of the fence, and large signs with writing in English that read: ‘Radiation – Do Not Enter.’”

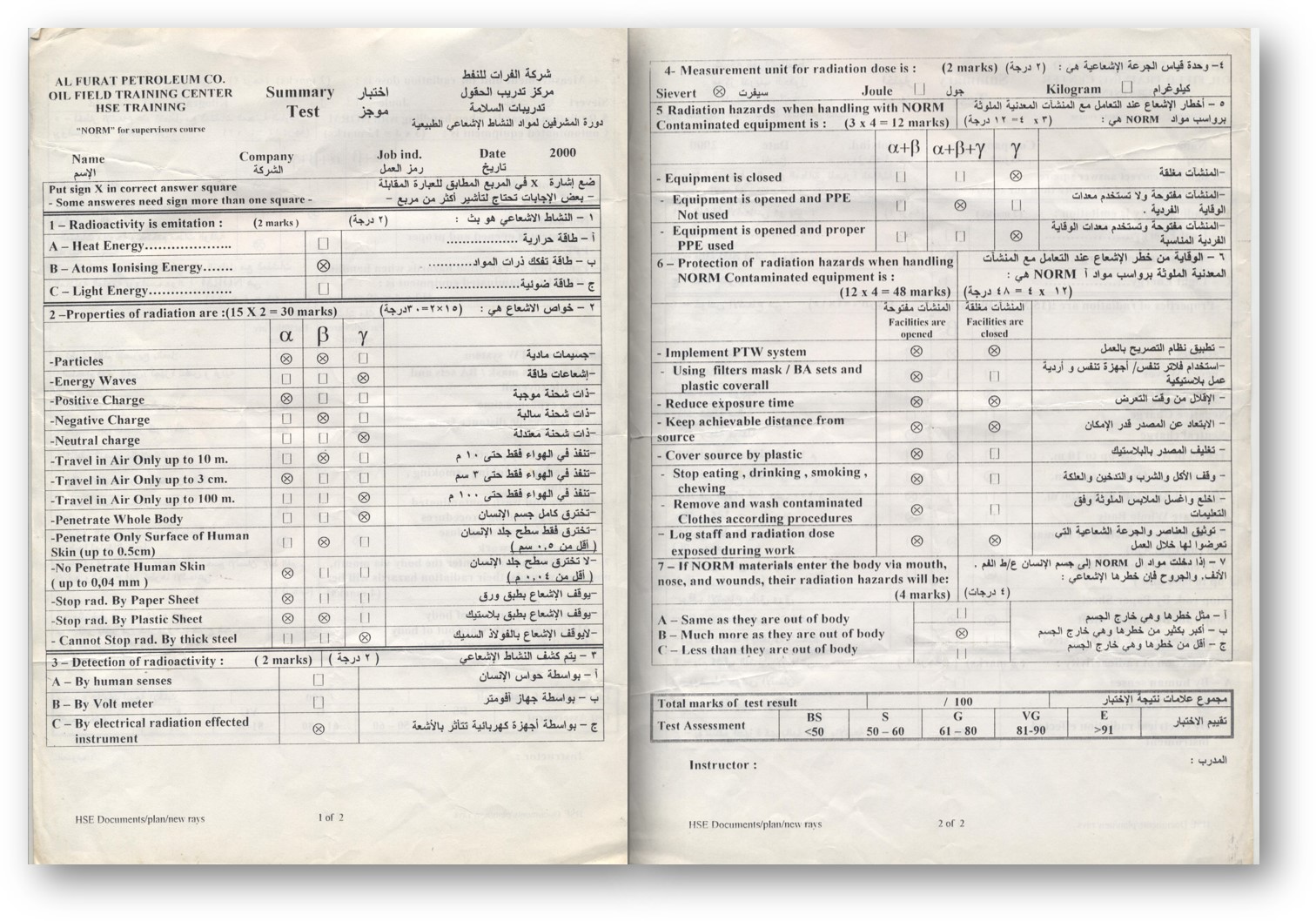

There was something else different about work in the Syrian oil fields. MacDonald had to take a 40-hour course on what’s referred to in the industry as Naturally Occurring Radioactive Materials, or NORM. The topic had come up in other oilfields but this was the first time he had been forced to formally learn anything, although it wasn’t much of an education. “The exam we took at the end had all the right answers already crossed in,” says MacDonald.

Image: AFPC NORM examination with answers already filled in.

Regardless, radioactivity was hardly on his mind in Syria. He stayed in a well-run workcamp that served a British breakfast and spent free time listening to rock music and drinking beers on the banks of the Euphrates River in the city of Deir Ez-Zor, part of a culturally-rich region that has been inhabited by humans for 11,000 years, and in more recent times was a brutal ISIS stronghold and flashpoint in the Syrian war.

The fateful day

On 1 August 2000, MacDonald was called out to check the Thayyem-107 well. It would be a fateful job.

A driver took him in a company SUV and he arrived at the well in the late morning, with temperatures boiling and the weather dry. A piece of piping connected to the wellhead called an expansion loop was corroded and had to be replaced. As MacDonald recalls it, his boss, a Shell official named Brian Welch, told him, “We need to replace this piping fast because this well is a big producer—go out there and make sure it’s done.”

To inspect the pipe, MacDonald had to put his hands inside the valve and run his fingers around the seal to feel for corrosion. He wore standard work boots and coveralls, but no gloves or respirator. Despite radioactivity being a known danger in Syria, he says he had never been informed by Shell before taking the job that the task involved contamination risks. And nobody mentioned anything about radioactive elements, which can hitch onto dust and blow about freely in the wind.

It’s an incredibly dangerous exposure pathway, because tiny dust particles can contaminate virtually everything they touch, such as a worker’s boots and clothes. They can also easily, and unknowingly, be breathed into the body or ingested when someone licks their dust-coated lips. That day at Thayyem-107 “was so damn hot and dry,” remembers MacDonald. “The valve was caked in dust, and I had my bare hands in the dust. Dust was in the air, and dust got all over my body.”

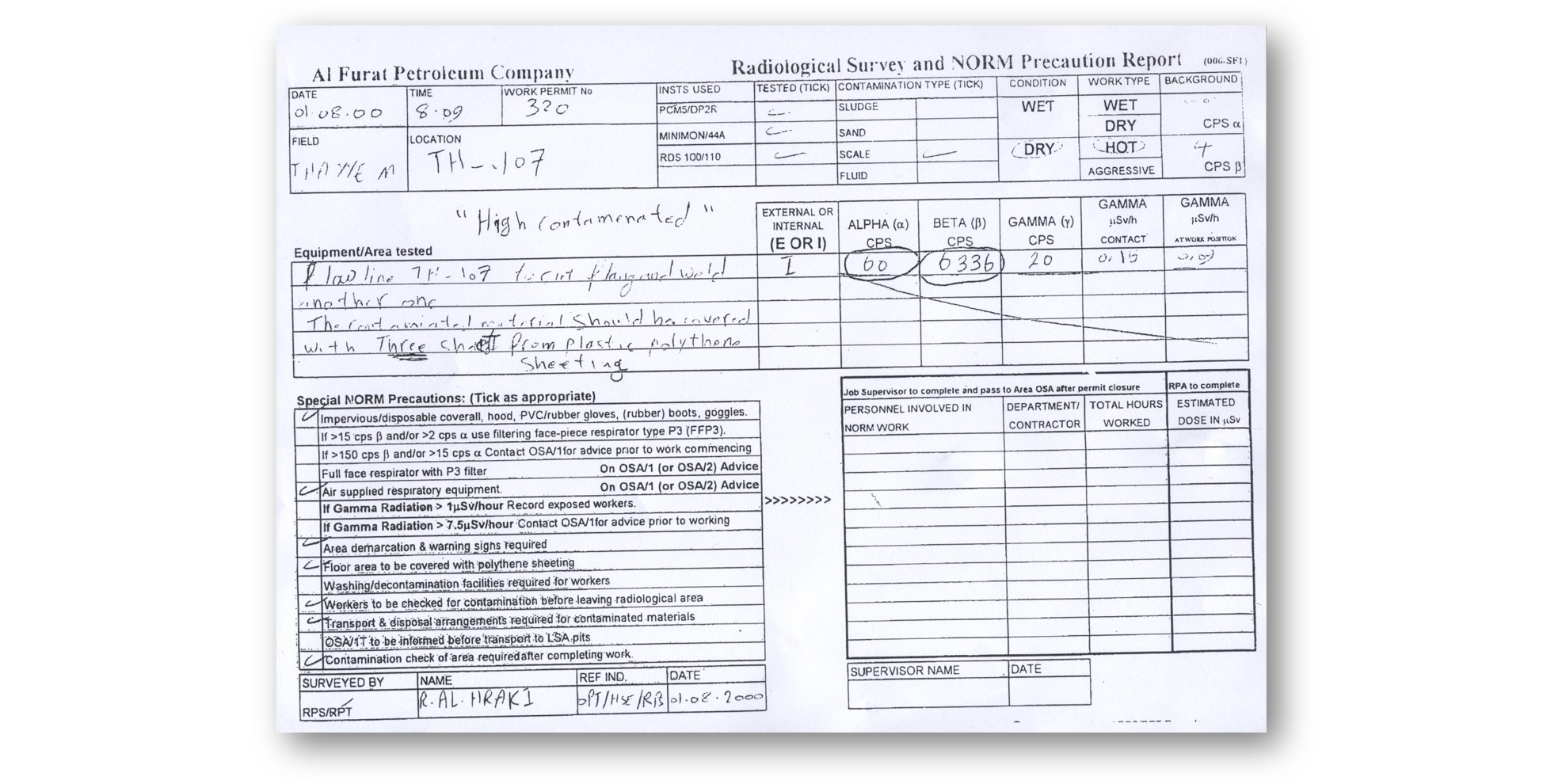

The valve was indeed corroded and would have to be replaced, but there wasn’t a replacement onsite. MacDonald ordered a safety test that would check the pipe’s strength, then walked off to smoke a cigarette. He had been at the wellhead for 45 minutes. It was now near noon and blazing hot. He stepped inside a little cabin that served as an office to make a cup of coffee and wait for the safety test. A paper on the desk caught his eye: “Al Furat Petroleum Company Radiological Survey and NORM Precaution Report.”

It revealed that at 8:09 that morning a radioactivity inspection had been conducted at the Thayyem-107 well and the numbers were off the charts. In fact, the report stated that in order to do work on the site, rubber gloves, rubber boots, goggles, an impervious coverall and air supplied respiratory equipment were all needed. Plus, the area was to be protected by warning signs and workers were, “to be checked for contamination before leaving [the] radiological area.” None of these protocols had been followed.

Image: NORM precaution report showing the types of protective equipment necessary at the site Keith MacDonald worked.

One way to measure the amount of radioactivity being given by a surface or object is with a scientific unit called Counts Per Second, or CPS. According to the report MacDonald found, the background level of radioactivity at the site was four CPS. The Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission says an area is considered a “hot zone” at five CPS. Yet, the report MacDonald had found indicated readings at the wellhead for beta particles, a type of radioactivity that can pass through skin and cause genetic mutations and cellular damage that leads to cancer, of 6,336 CPS, an astonishing 1,584 times background levels.

“It’s a pretty darn big exposure,” says Dr. Marco Kaltofen, a US nuclear forensics scientist at Worcester Polytechnic Institute with two decades of experience examining radioactivity around the world. (Kaltofen has testified as an expert witness on radioactivity in numerous legal cases and before the US Environmental Protection Agency; DeSmog passed him the report MacDonald had found).

“This worker certainly has a potentially large internal exposure from ingestion or inhalation or both,” Kaltofen added, “under normal circumstances this type of exposure should have generated a nasal swab and urine or fecal test of the worker.” MacDonald received no such thing.

He dashed back into the heat, horrified over the harm he had so quickly and silently bestowed upon his body, furious that he was not informed by his seemingly trustworthy superiors, and completely unaware of the depths of the rabbit hole he had just stumbled down.

“I asked the Syrian workers if they knew there was radiation there and they looked at me like I had just landed from Mars,” says MacDonald. He had the impression that “it was obvious they were being kept in the dark.”

MacDonald and the Syrian workers at the site were not the only ones. To this day, much of the world remains in the dark on the topic of oil and gas radioactivity, and nowhere is the lack of knowledge so stark as with the industry’s own workers, who are regularly lulled into a false sense of security.

Regulatory agencies, weakened in countries like the UK and US by defunding and deregulatory efforts, are unable to ensure safety standards are effectively met. A lack of attention from the media and medical community mean stories go untold. And oil and gas operators generally fail to fully inform their workers of the risks, despite knowing they exist. That combination of factors means MacDonald’s story is just the tip of the iceberg.

The industry has known

Nearly everyone on earth uses oil and gas products. But most people are completely unaware that oil and gas production brings large amounts of radioactivity to the surface.

The first scientific record comes from a 1904 paper by a University of Toronto researcher who examined crude oil from a well in a farmer’s field in southern Ontario. He discovered a radioactive gas we now know to be radon, which is currently pegged by the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) as the second leading cause of lung cancer in the United States. Radon is just one of many radioactive elements oil and gas brings to the surface. “The presence of these naturally occurring radionuclides in petroleum reservoirs,” states a 1991 EPA report, has actually been used, “as one of the methods for finding hydrocarbons.”

Much of the radioactivity brought to the surface in oil and gas production is part of a salty toxic stream of liquid the industry calls brine or produced water. Most oil wells produce far more brine than oil, and some wells can produce 10 times as much. Geologists have long known that the radioactive element radium, peppered throughout earth’s layers and moderately soluble, flows with brine to the surface. “We have created a transit system for taking radioactivity from underground,” says Kaltofen, the US nuclear forensic scientist, “bringing it up to the biosphere where it can interact with people and the environment.”

Because radium accumulates in oilfield piping — part of a difficult to remove deposit called “scale” — and sludge at the bottom of tanks, certain workers can become coated in radium-laden waste. The radioactive element can also easily be made airborne with dust, and accidentally ingested or inhaled. The US EPA has reported that each oil well generates approximately 100 tons of scale annually, and that conventional oil production alone produces 230,000 metric tons of radioactive sludge a year.

In the United States, because of exemptions written in 1980 by a pair of Democratic Congressmen, this hazardous waste, which according to the US EPA contains not just potentially concerning levels of radioactivity but also potentially concerning levels of carcinogens like benzene and toxic heavy metals like lead and arsenic, has been deemed “non-hazardous.” This means it can be disposed of in landfills intended to hold household garbage. There is little easily accessible information available on just where the rest of the world’s massive amounts of radioactive oil and gas waste ends up.

A 2005 report of the Norwegian Radiation Protection Authority reveals it has been standard practice in the North Sea oilfields to dump toxic radium-laden brine into the ocean. While the report indicates that in most areas background levels of radium would not change, “in limited areas in the northern North Sea, a doubling of the activity concentration … could be encountered.”

Much of this radioactivity is transported towards the Norwegian coast, the report notes. “To place this into context,” states a 2016 report of the International Association of Oil & Gas Producers (IOGP), co-authored by retired Shell radiation expert Gert Jonkers, the North Sea oil industry’s emissions, by one measure of radioactivity, “are forty times those reported by the nuclear energy sector.”

While today the oil and gas industry does not talk openly about the risks radioactivity poses to their workers, they once did. “The presence of natural radioactivity in oil and gas fields has been recognised worldwide,” states a 1987 document from the UK Offshore Operators Association, a leading trade association for the UK’s oil and gas industry.

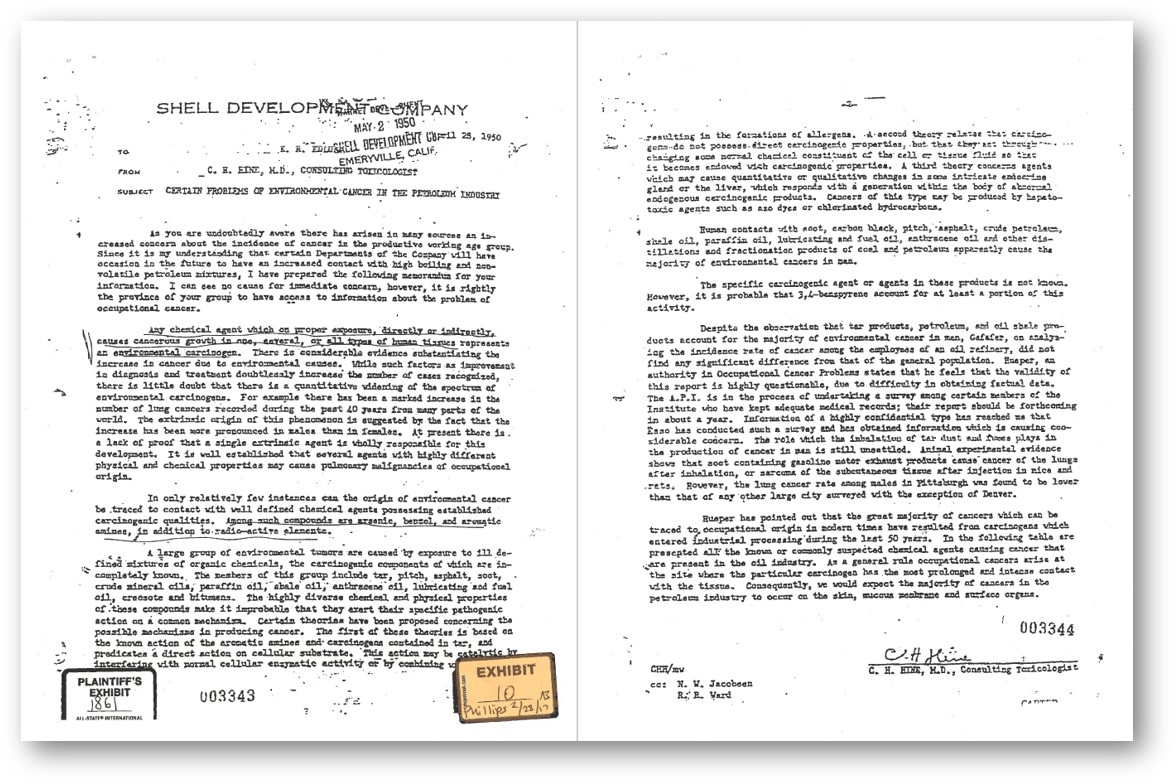

Shell is aware of the issue too. The company’s own documents reveal that the oil and gas giant has known for 70 years that various exposures from oil and gas work, including exposure to radioactive materials, can lead to cancer.

“Human contacts with soot, carbon black, pitch, asphalt, crude petroleum, shale oil, paraffin oil, lubricating and fuel oil, anthracene oil and other distillations and fractionation products of coal and petroleum apparently cause the majority of environmental cancers in man,” states a 1950 report produced by a toxicologist working at Emeryville Research Center, a bygone Shell lab in California. Substances like “arsenic” and “radio-active elements” are unique, the report notes, as they have “established carcinogenic qualities” for which the “origin of environmental cancer” can actually “be traced”.

Image: Opening pages of the Emeryville Research Center report (1950).

More recent documents from Shell indicate that through the fracking boom of the 2000s, knowledge of the risks of radioactivity has not been lost. In fact, Gert Jonkers, the retired Shell radiation expert, has authored or co-authored half a dozen papers on the topic.

“The encounter of Naturally Occurring Radioactive Material (NORM) is of increasing concern for the oil and gas industry, not only because of radiological safety aspects, but also from an environmental point of view,” states one 1997 article, published with the American Petroleum Institute. Another paper discusses how NORM “is often encountered during gas and oil production” and “gives rise to increased health hazards to personnel.”

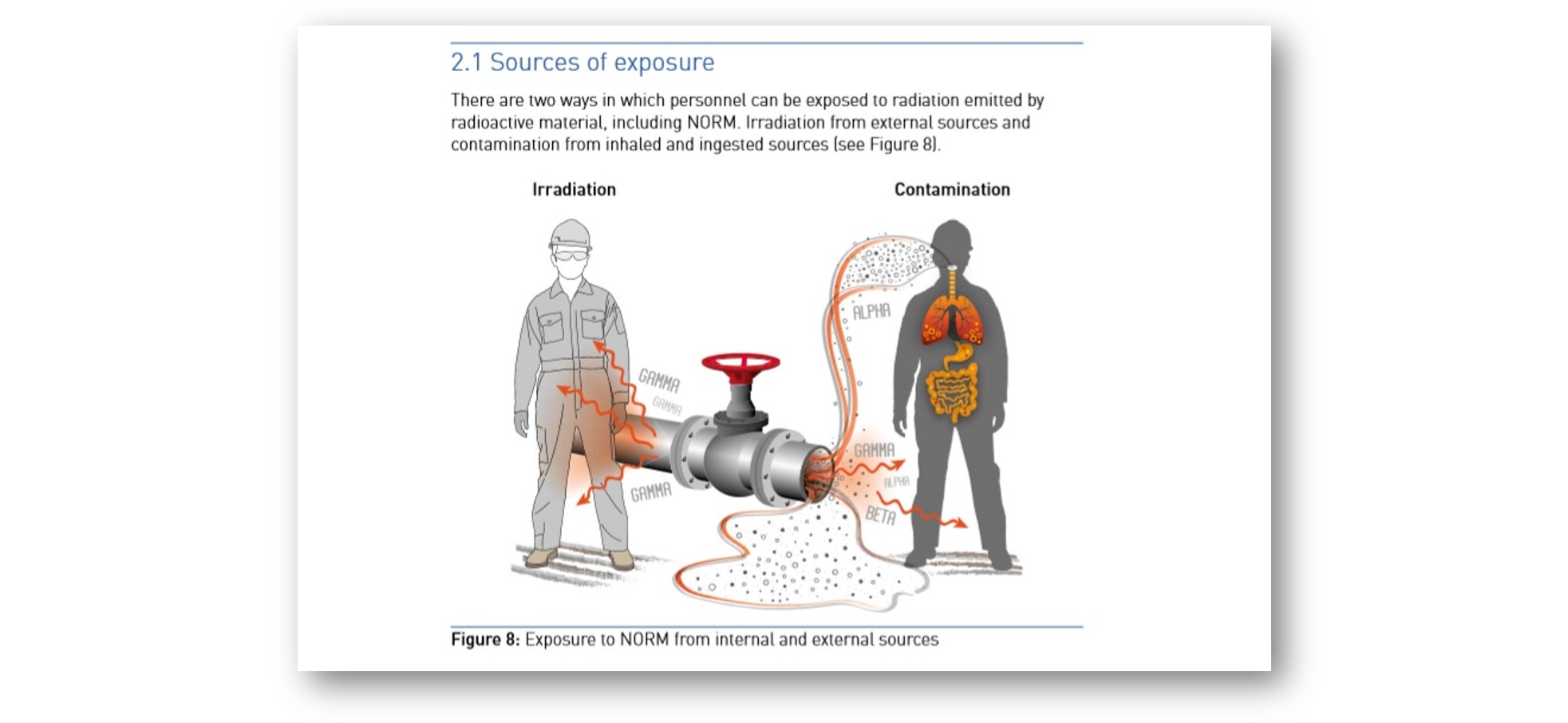

The 2016 report on radioactivity that Jonkers co-authored for the International Association of Oil & Gas Producers serves as an informative field guide to these hazards. “There are two ways in which personnel can be exposed to radiation,” the report states, “irradiation from external sources and contamination from inhaled and ingested sources.”

An accompanying diagram features an oil and gas worker standing above an open pipe spewing radioactivity, a hauntingly similar version of the situation MacDonald found himself in at Thayyem-107. While radioactivity can damage the skin, breathing or ingesting dust allows the hitchhiker radioactive elements, or radionuclides, to enter our bodies, where they may lodge in the lung or gut and continue their radioactive decay, leading to the “irradiation of tissues and organs.”

Image: Diagram of NORM exposure from the International Association of Oil & Gas Producers report.

But while Shell scientists may be schooled on the matter, workers like MacDonald, labouring in the company’s gritty and far-flung oil and gas fields, appear to be left to fend for themselves. And the company does not seem willing to fill in the blanks.

“While the risk of exposure to radioactive elements in some phases of our operations is low,” Shell spokesperson Curtis Smith replied to me in early January, “Shell has strict, well-developed safety procedures in place to monitor for radioactivity as well as a comprehensive list of safety protocols should radioactivity be detected.”

When pressed in March on the details of these safety procedures, and the commonness of a case like MacDonald’s, Smith replied, “unfortunately, all of our resources are dedicated to current/fluid events related to the COVID-19 outbreak. As a result, I won’t have the time to revisit this topic with you.” When pressed again in April regarding the specifics of MacDonald’s case, including a copy of the Thayyem-107 radiological report, Smith replied with the following statement:

“Safety is a top priority in all our operations and we take seriously any allegations that our operating companies might have a negative impact on employees, contractors or local communities. However, since Shell is not the operator in Syria but a minority shareholder in Al Furat Petroleum Company (AFPC), we do not hold nor have access to any operational level data owned by AFPC which can substantiate these claims.”

Andrew Gross, a US-based Radiation Control Consultant who for years ran a business cleaning up the oil and gas industry’s radioactive waste, and now works as an independent consultant, has little doubt where the buck stops.

“These companies will pretend they are ignorant but you got to remember these are corporations, and Shell or whoever it is has one purpose in life, to maximize profits,” says Gross. “If you are a worker, that is something important to understand,” he adds. “These guys need to know that they have to take care of themselves.”

Regulatory failures

MacDonald has been trying to get someone to take his story seriously for 20 years.

One of many legal firms he contacted was Thompsons Solicitors, headquartered in London. A June 2018 letter from attorney Stephen Ireland conveys an acknowledgment of the situation MacDonald encountered at Thayyem-107. “You believe that as a consequence of this exposure, you have developed a psychiatric/psychological disorder and skin lesions” the letter stated. But Ireland’s letter also noted that MacDonald’s legal claim was far from certain.

In fact, according to Dr Andrew Watterson, an occupational and environmental health researcher at the University of Stirling in Scotland, it is exceptionally difficult to get compensation. “The government’s workplace compensation scheme is an unholy mess,” he states in a 2015 article he co-wrote for Hazards Magazine. For workers to receive compensation they must usually show their illness is twice as likely to occur in their profession as compared to the general population. This is an “all-or-usually-nothing conservative epidemiology,” writes Watterson, “designed to give as many victims as possible a big fat zero.”

Watterson said he was not aware of a single worker case on oilfield radioactivity being brought before courts in the UK. There is a “lack of awareness” on the issue, he says, which means there are no detailed scientific studies and no case law to build from. But the primary problem in his opinion lies with “toothless” health and safety regulators. “In the UK, we have a vicious circle on occupational cancers,” says Watterson. “Don’t look, don’t find, no problem.”

Read more – DeSmog Special Series – Louisiana’s Cancer Alley Communities at Risk

When DeSmog asked the Health and Safety Executive, the UK agency responsible for regulation and enforcement of workplace health and safety, if it had ever assessed oil and gas worker cancers to determine whether or not a link could be drawn to occupational radioactivity exposures, an HSE spokesperson told DeSmog: “There have been numerous epidemiological studies into radiation exposure within the UK over the last 70 years but as far as I am aware there is nothing at present within the UK oil and gas [industry].”

Other aspects of HSE’s radioactivity policy convey that for the oil and gas industry, regulations largely rely not on government regulators, but self-enforcement. In the agency’s 176-page Approved Code of Practice and Guidance for Work With Ionising Radiation, there is just one fleeting reference to the oil and gas industry. An HSE document entitled Offshore Radiation Essentials states to the industry: “Following the guidance is not compulsory and you are free to take other action.” HSE told DeSmog, “the protection of workers is the responsibility of the companies.”

Part of the problem is a trend in countries such as the US and UK toward deregulation, and the weakening of environmental laws and the regulatory agencies that enforce them. In recent decades, the the Conservative-led governments have cut funding for the Health and Safety Executive, and the previous Labour government neglected its funding. “There is an ideological commitment to cutting red tape, then there is the practical act of cutting staff and regulators,” explains Watterson. “It goes back to [Conservative Prime Minister Margaret] Thatcher, she wanted to see softer regulation in the UK, and that was picked up by [Labour Prime Ministers] Blair and Brown.”

There is a sign of hope for workers like MacDonald. A court case settled in 2016 in the state of Louisiana, in the heart of America’s conventional oil and gas patch, reveals that dozens of workers working a variety of common industry jobs such as roughneck, roustabout, pipe cleaner and truck driver developed cancer.

A report written by radiation experts uses an analysis program created by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to link these worker’s cancers to radioactivity exposures received on the job. Cancers the workers developed include non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, various leukemias, colon cancer and liver cancer, among others.

“These men are guinea pigs,” says Stuart Smith, the New Orleans-based attorney who tried the cases, and was the first attorney to try oil-field radiation cases. “I have litigated several cases that showed that oilfield waste caused cancer,” he says. “All the big majors have known about this for many decades. The regulators are obviously aware of it too, it’s just that they don’t have the political cojones to do anything about it.”

Personal tragedy

MacDonald was furious with his superiors at Shell who had failed to inform him of the radioactivity risks at Theyyem-107. He had also been seeded with a horrible dread – that the high dose of radiation he received had forever mutated his body.

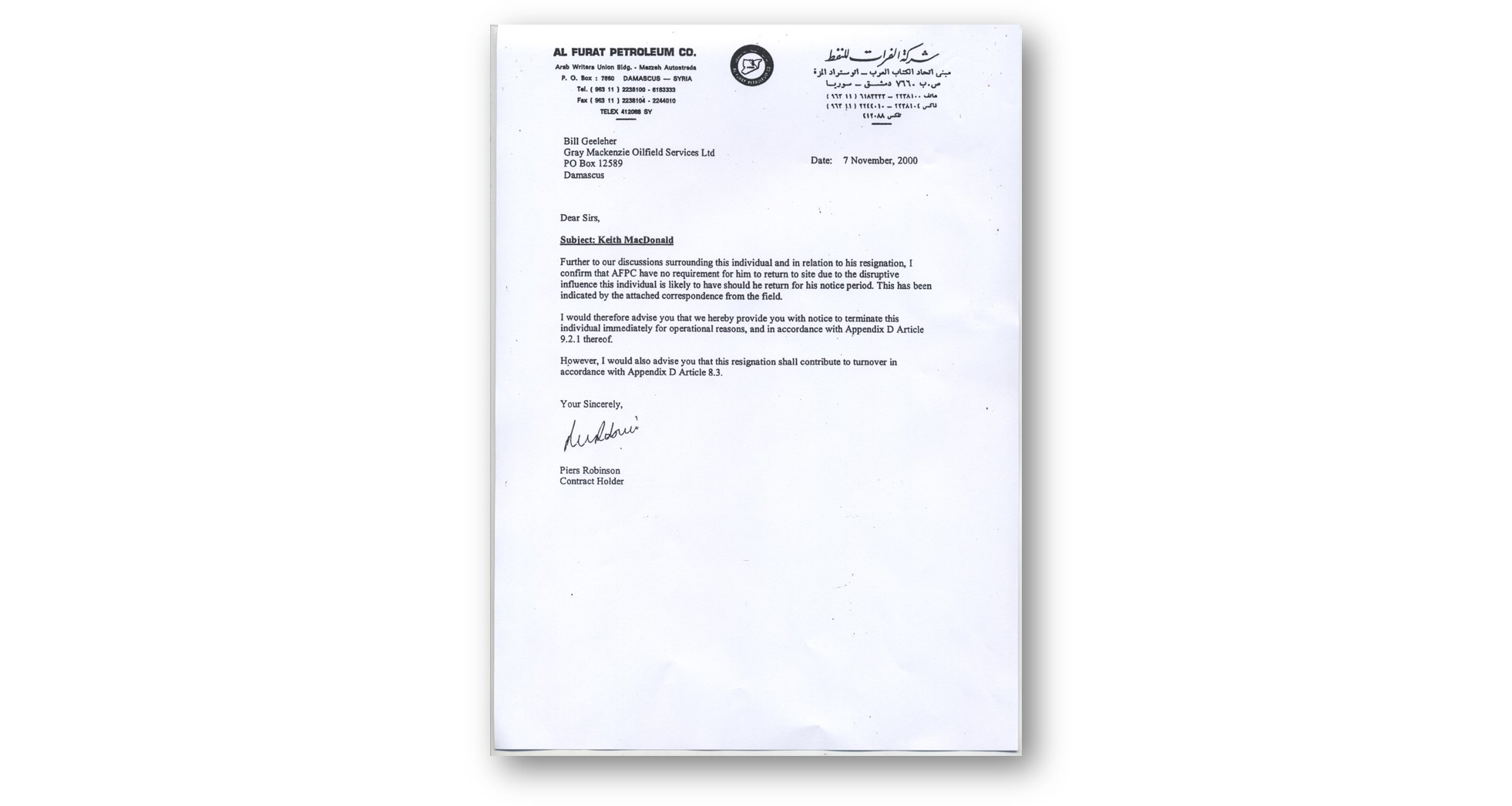

On the afternoon of 1 August 2000, he filed a report detailing his visit to Thayyem-107. “Specific methods for protection of personnel and the environment…were not applied,” it stated. He tried to get colleagues to listen to concerns but says he was treated like an outcast. A 7 November 2000 letter from Al Furat Petroleum Company to Gray Mackenzie, the UK-based oil service company that initially hired MacDonald for the Syria job, described him as a “disruptive influence.” The letter continued, “I would therefore advise you … to terminate this individual immediately.”

Image: A letter from AFPC to Gray Mackenzie suggesting the company terminate MacDonald’s contract.

But AFPC’s own investigation appeared to vindicate MacDonald. The underlying cause of the incident, their report stated, included the failure to follow working rules regarding NORM, a failure of communication, poor supervision, and a perceived pressure to finish the job in a hasty manner and ignore safety rules. On a scale of one to five, where one was slight injury and five was death, the report labeled the incident a three — “Major Injury”. Exposure, on a scale of A to E, was D — “High”. The report was signed by Robin Gardiner, an AFPC maintenance chief, and Brian Welch, a top Shell inspector.

Even this admission of error did not translate to compensation MacDonald thought he deserved. Lawyers and the judicial system had failed him. He grew despondent, and had trouble sleeping. In nightmares, cancer blossomed across his body. In 2005, while working in Kula Lumpur, Malaysia, MacDonald collapsed on the side of a busy city street. At a hospital he was fitted with a pacemaker. “There was nothing wrong physically,” he says – just crushing stress.

Then there was a high point. MacDonald had met his first wife, Sara, while working in the Philippines and together they set up home in the UK and had a son, Alastair. But the marriage ended in the 1990s, largely because of his work’s constant travel, says MacDonald. He wondered if he would ever have a stable family life.

Then, in 2006, while working for Chevron in Thailand, MacDonald met Kay. They married and moved to land owned by her parents in the countryside north of Bangkok. With his oilfield money, MacDonald built a veritable mansion: a five-bedroom house for his wife and her extended family.

“We had 40 acres of land and grew rice and corn, and we had chickens and pigs,” says MacDonald. A son, Calum, was born in 2007. In 2009, Scott was born. “I was in heaven,” says MacDonald. But just as swiftly as he had built a new world for himself, it crumbled.

In December 2010, Scott became sick. The diagnosis was Acute Lymphoblastic Leukaemia. For three years he was in and out of Bangkok General Hospital receiving treatments. MacDonald had a good job in Indonesia, working as construction superintendent for Saudi Aramco on a large project in the Straits of Malacca. He was making $24,000 a month and virtually all of it went to hospital bills. “I spent my life savings on medical treatment for Scott,” he says.

A photo from October 2013 shows father and son seated together in Pattay, a resort city on the Gulf of Thailand. MacDonald has a bandage on his right arm from an operation he had just received for a subdermal tumor. Scott is in a gray T-shirt, leaning on his father’s shoulder and smiling. He appears to be missing a tooth. They are both bald.

“That was the last time I saw Scott alive,” says MacDonald. He had just been released and doctors said there was a 94 percent chance he would survive. But Scott relapsed, and on 29 November 2013 he died, at the age of four and a half. “That knocked the guts out of me,” says MacDonald.

Then his own health took a turn. More cancerous skin lesions appeared and he returned to the UK for treatment. While physicians tended to blame his skin cancers on the sun, MacDonald remained convinced it was from his radioactivity exposure at Thayyem-107. “Whilst ultraviolet light remains probably the biggest factor in developing skin cancers,” wrote Sharon Blackford, a UK dermatologist who assessed his case in 2018, “the BETA particle exposure certainly could be contributory.”

But by that point MacDonald had fallen down an even more shocking rabbit-hole of research. He had discovered childhood leukemia shared a potential link with a father receiving a high dose of radiation.

A famous study published in 1990 in BMJ — formerly the British Medical Journal — examined a childhood leukemia cluster in northwest England near Sellafield, a sprawling nuclear power facility. Many suspected links were examined, such as consumption of local fish and shellfish, nearness of homes to the facility, and whether or not mothers had been exposed to various viruses during pregnancy or received pre-natal abdominal x-rays. The link of statistical significance, researchers found, lay in the occupation of the sick children’s fathers, many of whom worked at the nuclear facility and had received elevated radioactivity exposures in the months leading up to their wives’ conception. “This result,” the authors concluded, “suggests an effect of ionising radiation on fathers that may be leukaemogenic in their offspring.”

The paper remains controversial. But when DeSmog put the question of whether MacDonald’s exposure in Syria could have led to his wife, eight and a half years later, giving birth to a son who would die from leukemia, Marco Kaltofen, the US nuclear forensics expert, said the question “was not crazy.” While a mutated sperm would not live long, says Kaltofen, in MacDonald’s case, radioactive elements accidentally ingested and inhaled would still be inside of him, blasting off harmful radiation. In fact, radium-226, the primary isotope of concern on pipes such as the one MacDonald examined has a half-life of 1,600 years.

Still, to firmly link Scott’s death to MacDonald’s cancer, a person with a combined expertise that includes a medical physician degree and a PhD in toxicology would have to examine the case, says Kaltofen. Unfortunately, they are few and far between. An even greater impediment to the truth might be a longstanding bias among this rarefied group of experts. “There is a real resistance in the health physics community to teratogenic radiation effects, meaning that exposure to an individual can effect the next generation,” says Kaltofen.”

Shell, however, is aware of the linkage. “Exposure to ionizing radiation, even at low doses, can cause damage to the nuclear (genetic) material in cells that can result in the development of radiation induced cancer many years later (somatic effects), heritable disease in future generations and some developmental effects under certain conditions,” states the 2016 International Association of Oil & Gas Producers paper on oilfield radioactivity, co-authored by retired Shell radiation expert Gert Jonkers.

More cases?

MacDonald remains convinced the negligent exposure he received while working for Shell in the oilfields of Syria led to the death of his son from leukemia and his own skin cancers, whatever the courts and toxicologist say. What worries him most is that he is not alone; that he is member of a vast hidden army of oil and gas workers who have been contaminated in oilfields the world over. And many of them may have received high exposures regularly, and over a much longer timespan.

Frances Leader, a Corfe Mullen resident who lost her husband Tony, a former North Sea oilman, to non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma in 2013 remains convinced radioactivity exposure during his time on rigs in the 1970s and early 1980s was the cause. The contamination, she believes, came from the drilling fluids and produced water that spilled all over men like Tony every time pipping was pulled up on deck. Additional exposure, she suspects, came from sludge in tanks located in the base of the rig that she says Tony regularly had to clean. “They wore no breathing apparatus, no protection, no dosimeter, and there was never ever any mention of radioactivity—none,” says Leader.

Read more – DeSmog Special Series – A Just Transition: From Fossil Fuels to Environmental Justice

How many UK oil and gas workers share a similar fate is unknown, because no one has ever tried to search for and tally the cases. How many workers around the world have been harmed by radioactivity is an even greater mystery.

“The Syrians were basically deemed disposable,” concludes MacDonald, recalling his time with Shell in the Middle East. “They were green as grass and hadn’t been told anything. Guys were allowed to go into contaminated areas without any monitoring, and operators took no precautions.”

MacDonald realises that not everyone has the documents and evidence that he has been able to obtain over the years. And not everyone feels confronting one of the most powerful industries on earth is their only remaining option. “The industry is terrified to expose any of this knowledge because there are too many people with billions and billions of dollars invested,” he says. “At the end of the day I want to prove beyond a shadow of a doubt that this is not an isolated incident, and there are other people being exposed.”

“No one give’s a shit, but I give a shit,” he adds. “This is all preventable, and if my coming out can save one life, then it was all worth it.”

Main images credit: Public Domain. Composite credit: Zak Derler

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts