Ohiauga, a remote village in Nigeria, needs a hospital. Seven years ago, it almost got one.

In 2012, the oil and gas company Total E&P Nigeria, a subsidiary of Total SA, promised to build a modern health centre to compensate the community for an explosion from one of the gas pipes that runs through the area, a disaster which killed the community’s crops and polluted its drinking water.

It was a welcome gesture. Ohiauga is about 20 kilometres from the nearest hospital, and, with no public transport available, a 25-minute motorbike ride is often the only option for those who are sick or in labour. For pregnant women, the journey is often impossible, and the consequences can be dire. So the company cleared the land, and constructed the building that would one day soon house medical equipment, doctors and nurses.

Then Total disappeared. Today, a crumbling building surrounded by thick vegetation is the only reminder of the hospital that could have been.

Disappearing act

Ohiauga is in the Niger Delta region of Nigeria, an enormous wetland landscape with a long history of dealing with the negative impacts of the oil and gas industry. Shell began pumping oil in the nearby Bayelsa State in 1956, and several other international companies subsequently moved in to capitalise on the region’s natural resources, leaving a legacy of oil spills and pollution.

Despite the environmental devastation that the industry has caused, and the need to reduce fossil fuel consumption to tackle climate change, Nigeria is planning to expand its oil production, almost doubling its output by 2025.

A local activist named Bright Abali was the first to call on Total to build a hospital in Ohiauga following the 2012 explosion, which took place about 45 kilometres outside the village.

Abali was out of the country when the explosion happened, but soon returned and started agitating through his social media channels for the company to compensate the community for the damage, as well as writing to the company to request a hospital.

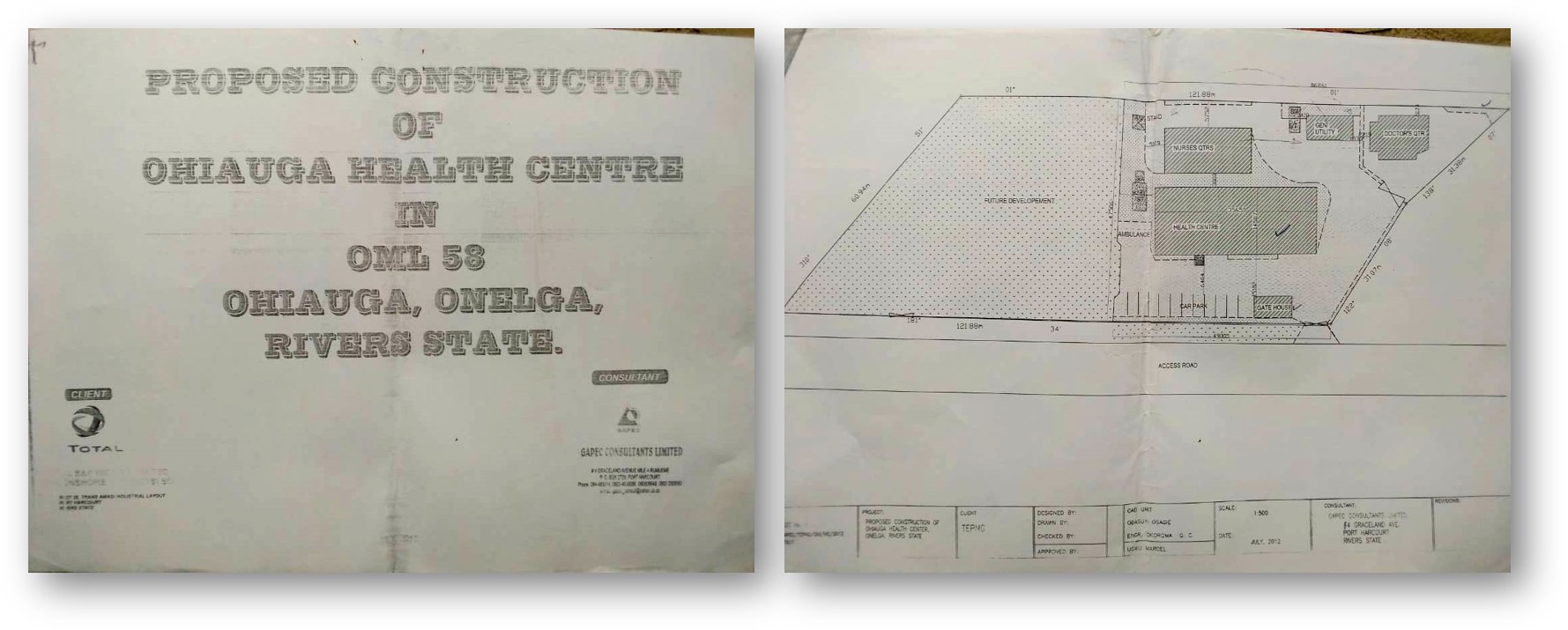

Image: Plans for the health centre in Ohiauga to be built by Total

Initially, Total was hostile to his efforts. “I was humiliated, detained by a security agency for stating the facts,” Abali says. “I was accused of plotting negative things against the company. We received gimmicks to silence the impacted communities.”

But Total eventually agreed to Abali’s demands for a health centre, agreeing to provide almost $300,000 in two stages. The first half would go towards building the hospital, and the second half would equip it with medical supplies.

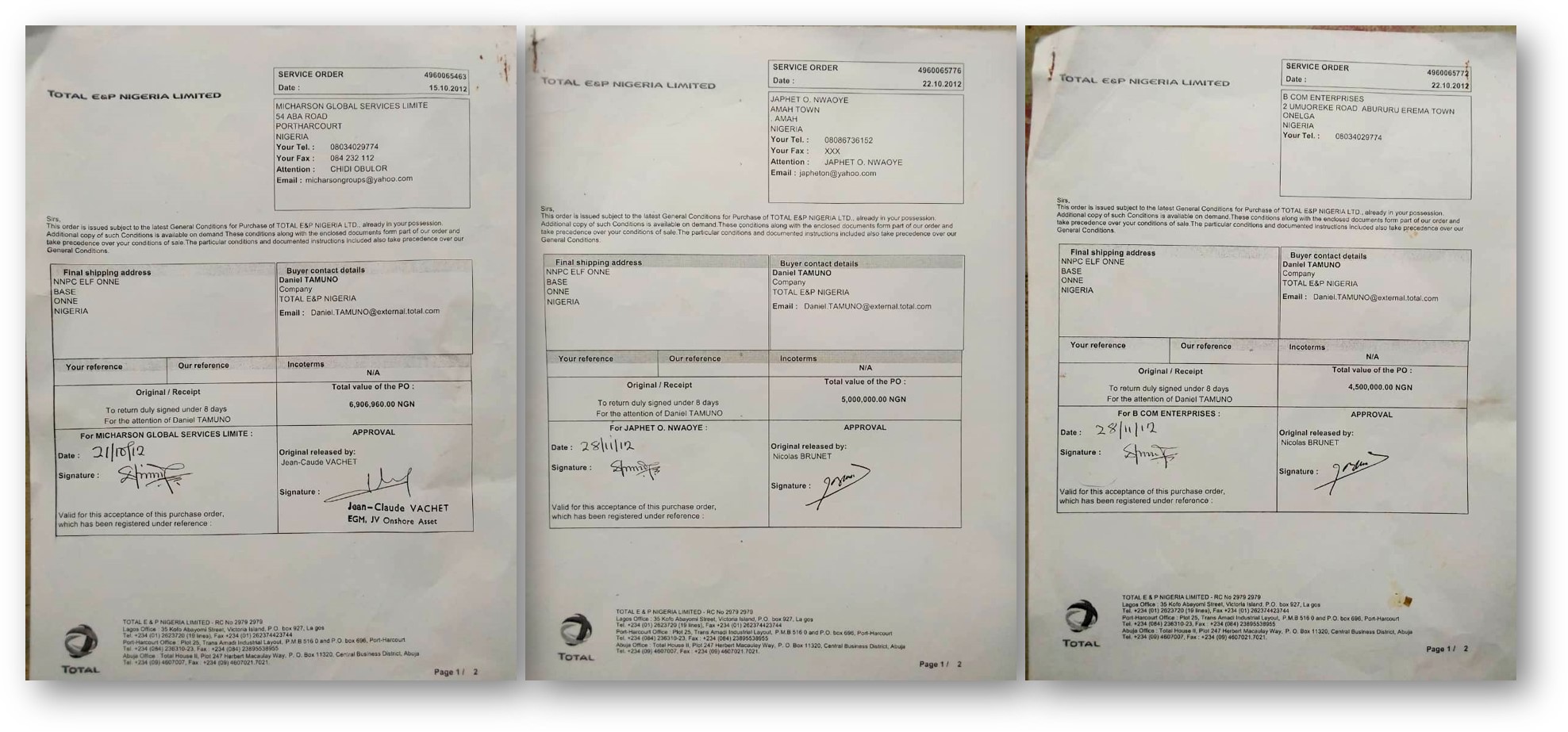

Purchase orders sent by Total, dated October 2012, show the provisioning of the first round of construction. The documents are signed by Nicholas Brunet, then Deputy Director of Total E&P Nigeria.

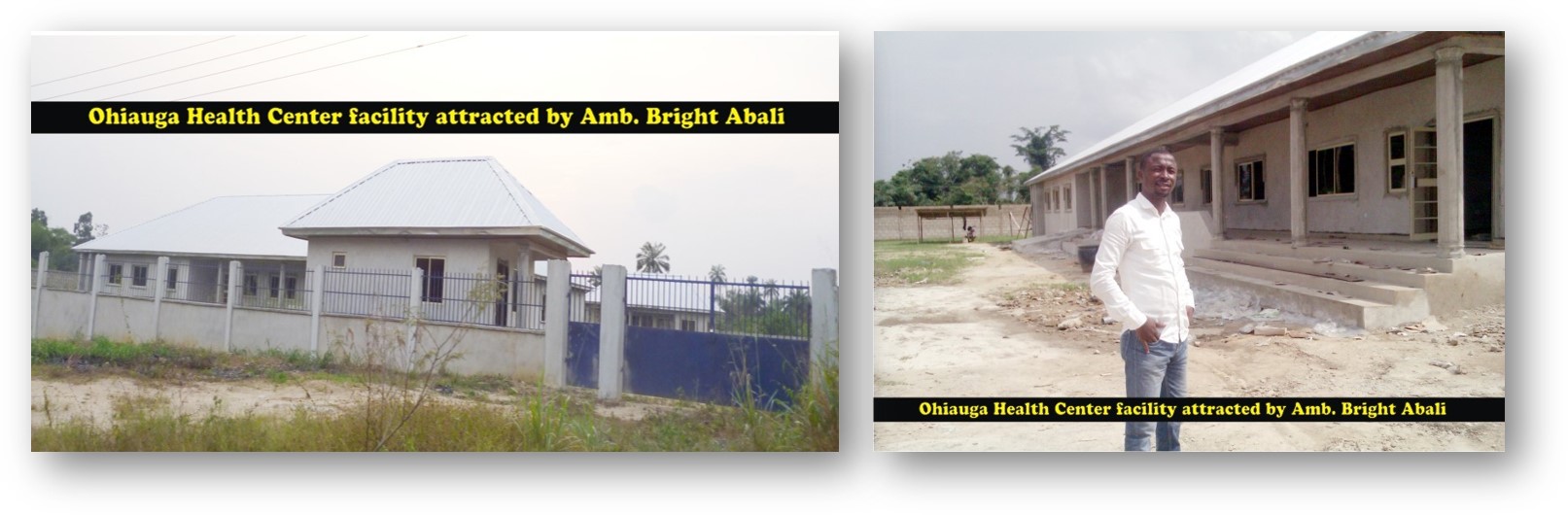

Initially, Total honoured its commitment, and the structure of the health centre was completed in June 2013. Photographs from that time show a clean, white building in a gated compound, with a mud track leading to the facility. DeSmog called the contracting company, which confirmed the building work had been completed.

But then Total vanished, and it has given no signs that it intends to complete the project in the seven years since. A spokesperson for Total Nigeria, Charles Ebereonwu, denied any knowledge of the project.

When DeSmog visited the site in January 2020, the evidence of Total’s abandonment was clear. The building is inaccessible and decrepit, buried beneath a mass of bushes and long grass.

Image: The built health centre, with Bright Abali, who lobbied Total to build it.

“It’s a good thing that Total decided to build this hospital, but we appeal to the company to come finish the project they have started,” says Smart Nwakiri, president of the Ohiauga Youth Association.

It’s not clear why the oil company abandoned the hospital. The region experienced a period of conflict that began in 2015, two years after the hospital was abandoned, which ended in 2017. The community believes that it’s time for Total to make good on its commitments.

“The crises which happened years back made everyone afraid. Even the Total officials were afraid. But now that there is peace, they ought to have completed the work,” says Clement Agbam, the community leader of Ohiauga.

Consequences

Meanwhile, residents of Ohiauga continue to suffer from the lack of healthcare facilities, with many relying on the overburdened local pharmacy for treatments. Janet Saturday Ajeh, the pharmacist, says that many of those who come to her have high blood pressure.

“I give them drugs, and if it is something that requires an injection, I will give them the injection,” she says.

But that cannot compensate for the absence of a properly equipped hospital, especially for pregnant women, who instead have to rely on traditional birth attendants. Each motorbike ride to the nearest hospital costs around 515 Nigerian Naira (about $1.40) – money that many residents of Ohiauga do not have.

Like what you’re reading? Support DeSmog by becoming a patron today!

The distance alone scares me,” says Gift Joseph, a young pregnant woman, adding that often she feels too unwell to make the necessarily regular journeys.

In some cases, Total’s promised hospital could have saved lives: in the years following the abandonment of the project, one patient died due to heavy bleeding following the birth of her child.

“Many pregnant women experience miscarriages and many women have hard labours,” said Madam Gold, who has been a midwife in the village since 1982. “It affects us a lot.”

Total’s abandonment of the health centre has had dire consequences for the community, with the crumbling structure creating added problems for a region that has recently been afflicted by conflict and criminality.

“We are worried because the hospital site has turned into a criminals’ den, overgrown by weeds, and is currently a security threat to the entire community and neighbouring communities,” says Abali.

Image: Purchase orders for the health centre

The building was constructed on land once used for farming, paid for by Total in the first tranche of funding.

“We used the place to farm cassava, vegetables, okra and fresh pepper,” says Obiusor Odiegba, a member of the family who previously farmed at the site. “But our people have been suffering going to Omoku for the hospital, and that is why we gave the land to Total.”

Meanwhile, the 2012 explosion continues to blight the community.

The community lacks the power to pump the clean water provided by the government, and have to rely instead on groundwater, which fills the village well for drinking, cooking and washing.

But members of the community say that this water was polluted by the explosion, and has yet to recover from the impact. DeSmog sent a sample of the water taken from the well to a laboratory for testing. The results showed that the water has high nitrate levels and is unusually acidic, rendering it unsafe for drinking.

Community plea

The community is now pleading with Total to return to Ohiauga and finish what they started.

In a letter dated 2nd December 2019, addressed to the Corporate Social Responsibility department of Total Nigeria, community leader Clement Agbam wrote to appeal to the “reputable company to Intervene and Re-award the remaining Phase(s) of the Ohiauga Health Project, to enable our community be releaved (sic) from challenges associated to the abandoned project and begin to enjoy the health facility.”

The abandonment of the project contradicts what Abali claims in on of his letters is Total’s stated commitment to see through any projects with host communities “within a reasonable time frame, to maintain our integrity and build confidence with all stakeholders”.

Meanwhile, Total has shown no intent to return to the project, and the company did not respond to multiple requests for comment, other than to deny all knowledge of the hospital.

The hospital – what is left of it – continues to crumble, and the community continues to suffer. The failure of Total to deliver on its promise is another piece of evidence in support of what many across the Niger Delta may already suspect: that oil companies are in it for themselves.

Editing by Sophie Yeo.

Images © Elfredah Kevin-Alerechi. Composite © DeSmog UK.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts