On August 7, after Geraldine Mayho’s funeral, her body was laid to rest in the St. James Catholic Cemetery in southern Louisiana, across the street from a cluster of oil storage tanks. The tanks are like those that surround the Burton Lane neighborhood in St. James where she had lived, and are emblematic of the type of polluting industry she spent her last years rallying against.

Viewing before Geraldine Mayho’s funeral at the St. James Catholic Church in St. James, Louisiana.

I met Mayho in 2017. She showed me suitcases and boxes she kept packed and waiting in her living room, in case she could find a way to afford to move. She was aware that the nearby oil storage tanks often leak the carcinogen benzene as well as other air pollutants, and with more petrochemical plants being built nearby, she desperately wanted out of the neighborhood.

Geraldine Mayho speaking at her home on Burton Street in St. James in 2017.

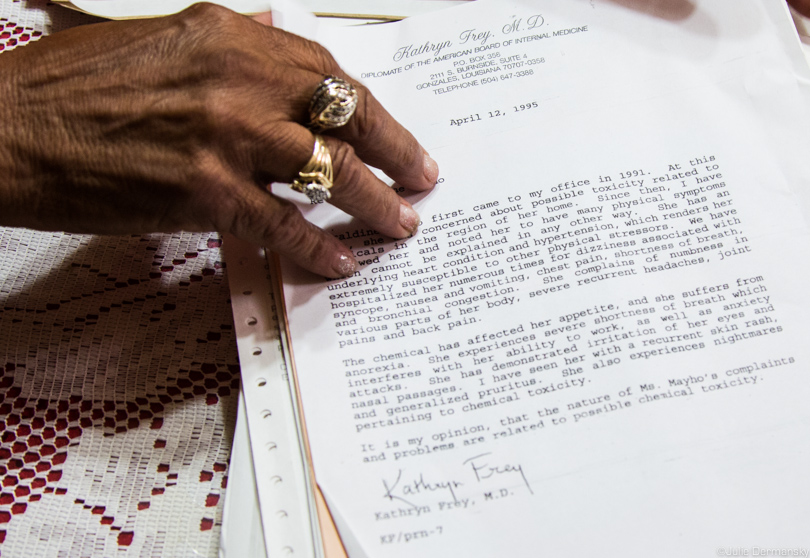

At that point, Mayho’s health was already compromised by her sensitivity to chemicals, a medical issue one of her doctors outlined in a letter two decades earlier. Today, less than three miles away from her home, the Chinese chemical giant Yuhuang Chemical is developing a $1.85 billion methanol facility, and other petrochemical plants are seeking permits to join the area, where the oil and gas industry has long had a presence. With these new developments looming over her, Mayho had constant anxiety about the toxic environment in which she lived her final years.

Mayho in front of her home on Burton Street across from oil storage tanks on February 12, 2019.

April 1995 letter from Mayho’s doctor concerning her health and “possible chemical toxicity.”

She never was able to move out. Mayho died on July 28 at age 76 from pneumonia following a stroke. A retired custodial worker from the St. James School District, she became an outspoken environmental activist in the years preceding her death.

Born in New Orleans in 1947, Mayho moved to St. James nearly 50 years ago with her husband, who died of cancer in 2012. St. James is a predominantly low-income, African-American town of less than a thousand, located 50 miles west of New Orleans in a highly industrialized stretch along the Mississippi River known as Cancer Alley.

The town of St. James lies in St. James Parish’s 5th District, a once rural area along the Mississippi that has been primed toward industrialization in the last few years. In 2014, local politicians changed the 4th and 5th Districts from “residential” to an ambiguous “residential/future industrial” designation in the parish’s new land use plan. In doing so, they jumpstarted the transformation of these districts into a burgeoning petrochemical haven.

Mayho railed against this industrial transformation of her community. She was an active member of the Humanitarian Enterprise of Loving People (H.E.L.P), a group that led the fight against the Bayou Bridge oil pipeline, which terminates in St. James and was installed in 2018 despite considerable local opposition. As that battle wound down, she became one of the first members of RISE St. James, a community group opposing a $9.4 billion Formosa chemical manufacturing complex a few miles from Mayho’s home. She also worked with the Coalition Against Death Alley (CADA), a Louisiana-based environmental and social justice movement seeking to stop further fossil fuel development and curtail existing pollution in the area.

There was plenty to keep Mayho busy. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has documented that air pollution levels for the chemical ethylene oxide, and its associated cancer risk, are higher than the national average for St. Charles Parish, home to a Union Carbide plant. That’s just next door to St. James Parish, where the proposed Formosa plastics complex Mayho fought is seeking a permit to release, among numerous other chemicals, up to seven tons of ethylene oxide a year. In late 2016, the EPA concluded ethylene oxide was at least 30 times more carcinogenic than previously thought.

And across the Mississippi River, in St. James Parish’s 4th district, Wanhua Chemical is planning to build a $1.25 billion plastics manufacturing complex, which would also release air pollutants into the surrounding area.

The last day the public can weigh in on the Formosa plant in St. James is August 12. Earthjustice, a nonprofit legal organization working with RISE St. James, offers an email form to send comments on the permit proposal to the Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality.

Geraldine Mayho at a St. James Parish Council meeting on April 19, 2017.

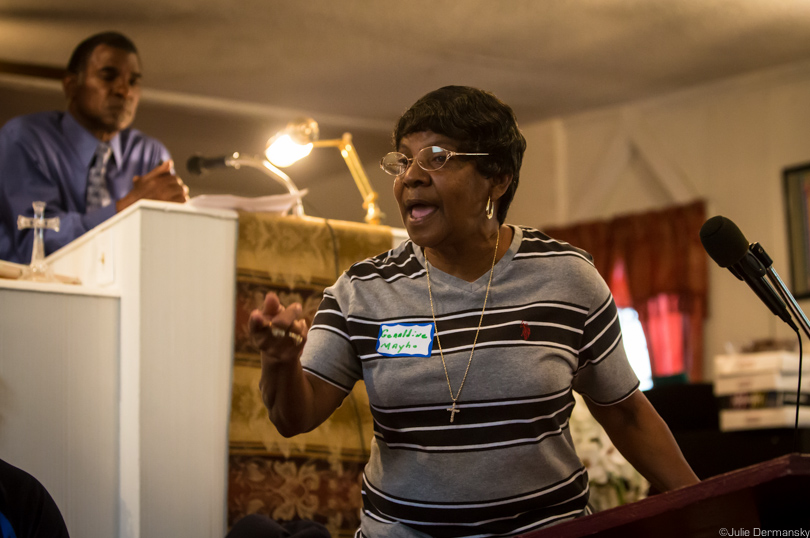

Geraldine Mayho sharing her story at a community meeting at the Mount Triumph Baptist Church in St. James on March 25, 2017.

It was Mayho and Sharon Lavigne, the founder of RISE St. James and fellow resident, who introduced me to the Burton Lane neighborhood of St. James and its vulnerable residents. Many who live there are handicapped and, because the area lacks a reliable evacuation route, could be trapped during an industrial accident or severe storm.

Geraldine Mayho and Sharon Lavigne with lifelong St. James resident Navis Prestley on Burton Street on June 24, 2018.

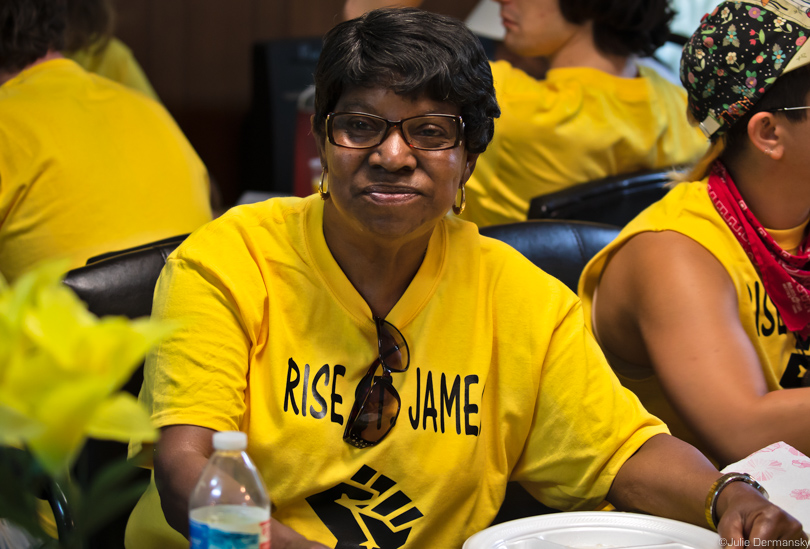

Mayho at a RISE St. James meeting on February 12, 2019.

“Instead of buying the people out, they are waiting for us to die off,” Keith Hunter, one Burton Lane resident, told me in 2017, referencing the wave of petrochemical companies moving into his residential neighborhood. “That is their plan. They don’t have to settle with us.”

Hunter died of respiratory failure the following year. After his death, Mayho worried that she would be next.

Pastor Harry Joseph with Sharon Lavigne following Mayho’s funeral in St. James.

Harry Joseph, pastor of the St. James Mount Triumph Baptist Church, reminisced about Mayho, who never missed a community meeting unless her health made it impossible to attend. “She was a good person that you could always count on to show up,” he said.

Geraldine Mayho at Mount Triumph Baptist Church in St. James.

“She was the best mom ever,” her son, Shondell Mayho, told me at the gravesite with tears in his eyes. “She did whatever needed to be done in the neighborhood. She was a brave lady, and always did what she thought was right.”

“Geraldine’s death won’t silence her,” Lavigne told me after the funeral. “She was a fighter. She didn’t mind speaking out. We won’t let her death be in vain. We will fight harder now in her honor.”

Geraldine Mayho with members of the Coalition Against Death Alley (CADA) praying at the site where Formosa plans to build a chemical plant in St. James, Louisiana.

Geraldine Mayho with a megaphone in front of the Governor’s mansion in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, on the third day of CADA’s five day march.

In June, despite her reliance on a walker, Mayho joined the Coalition Against Death Alley’s five day march through Cancer Alley. CADA members, wearing bright yellow RISE St. James t-shirts, were a noticeable presence at Mayho’s funeral. Other attendees wore yellow t-shirts emblazoned with her image and the words, “A true warrior gone home.”

Members of CADA wearing RISE St. James t-shirts in honor of Mayho at her funeral.

“My grandmother always made us aware of the pollution in St. James,” Natasha Johnson, Mayho’s granddaughter who lives in Arizona, told me after the funeral. Johnson worried about Mayho after the death of her grandfather in 2012. She feared both the worsening pollution in St. James and the prospect of new petrochemical plants being built near Mayho’s home, but Johnson did not know about her grandmother’s role in fighting both.

“She never mentioned she was marching against them, even though we spoke weekly,” Johnson said. “She had always been my hero growing up, but now she is even more than that.”

Geraldine Mayho with members of CADA on June 1, 2019, having breakfast at a church before a day of marching and protest.

Geraldine Mayho with members of CADA protesting in front of the Governor’s Mansion on June 1, 2018. The group wants Louisiana Governor John Bel Edwards to meet with Cancer Alley community members to discuss their concerns about air pollution.

Main image: Casket with Geraldine Mayho’s body being laid to rest in St. James, Louisiana. Credit: All photos and video by Julie Dermansky for DeSmog

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts