Last month, four residents from Louisiana neighborhoods impacted by air pollution traveled far from their Mississippi River parishes to Washington, D.C., and Tokyo, Japan, seeking help in their struggle for clean air.

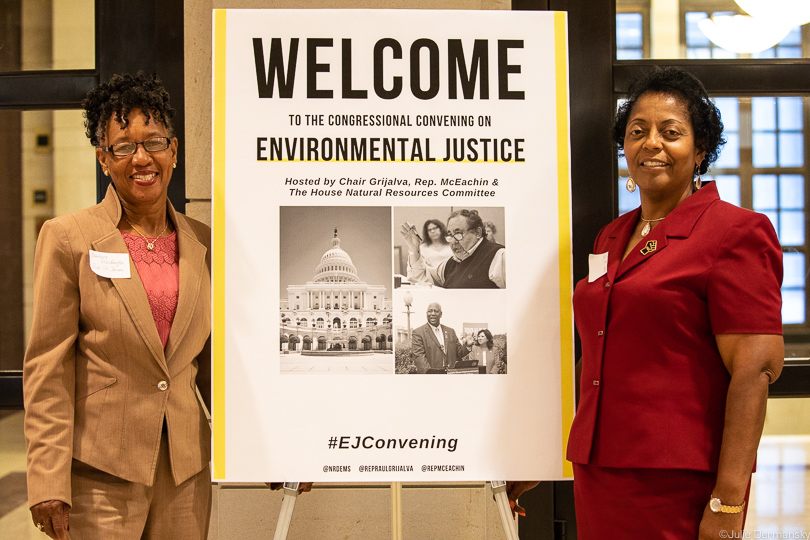

St. James Parish’s Sharon Lavigne and Barbara Washington, both fighting to prevent additional petrochemical plant construction near their homes, attended the Congressional Convening on Environmental Justice in Washington, D.C., on June 26.*

Barbara Washington (left) and Sharon Lavigne (right) in the visitor center of the United States Capitol.

Meanwhile, Robert Taylor and Lydia Gerard, hailing from St. John the Baptist Parish, flew to Tokyo, Japan. There, they aimed to gain entry to a Denka stockholder meeting to call attention to the way the company’s synthetic rubber plant, located in their neighborhood, is jeopardizing the community’s health.

The parishes of St. James and St. John the Baptist lie in the middle of Louisiana’s Cancer Alley, an 80-mile industrial stretch along the Mississippi River. It is also known as the “Petrochemical Corridor,” home to over 100 petrochemical plants and refineries, with even more in the works.

Bringing Environmental Justice to the Pelican State

Calls for environmental justice in Louisiana, an historically industry-friendly state, are growing. However, as these advocates’ efforts show, asking the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to uphold the “protection” in its name has been a tall order under the Trump administration — despite the President’s recent claims of American “environmental leadership.”

Beginning in late May, a coalition of environmental groups and residents, including Taylor, Gerard, Lavigne, and Washington, took part in a five-day march through Cancer Alley that ended at the State Capitol in Baton Rouge.

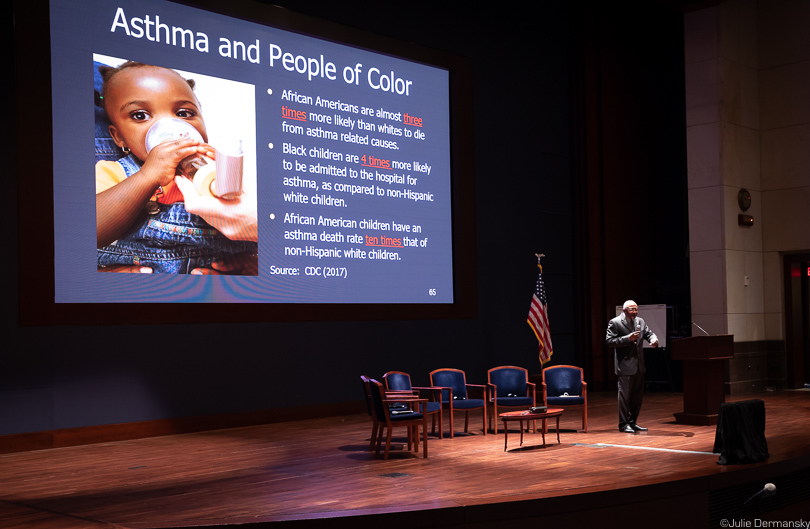

EPA’s own studies and those of the Union of Concerned Scientists show that communities of color have higher exposure rates to air pollution than their white counterparts; landfills, hazardous waste sites, and industrial facilities are more often located in their communities. Water contamination and lead poisoning disproportionately affect children of color while climate change impacts have a similarly outsize effect on low-income communities and communities of color. Despite this well-known history, the current administration is set on slashing the budget for the EPA’s environmental justice programs, while the agency rescinds rules to cut pollution from power plants and vehicles and boosts fossil fuel development.

Both Lavigne, founder of RISE St. James, a faith-based community group fighting for a healthy environment, and Washington are trying to stop a trio of petrochemical factories from being built in St. James Parish. They face an uphill battle as politicians on local, state, and federal levels have rolled out a red carpet to the plastic manufacturing industry, whose factories will be fueled by fracked natural gas, further polluting the air and water while contributing to climate change. The three projects coming to St. James if all of the needed permits are granted, are the Chinese-owned Wanhua chemical plant, the Taiwanese-owned Formosa plastic chemical complex, and the Texas-based Syngas methanol facility.

Taylor, founder of Concerned Citizens of St. John, and Gerard want the Denka Performance Elastomer synthetic rubber manufacturing plant in their neighborhood to lower emissions of chloroprene, a probable carcinogen, to the standard recommended by the EPA. According to the EPA’s most recent National Air Toxics Assessment, the risk of developing cancer from air pollution in the census tract closest to the Denka facility is nearly 50 times higher than the national average.

From St. John the Baptist Parish to Tokyo

Three years after the St. John the Baptist community learned that residents are exposed to chloroprene levels that are frequently hundreds of times greater than the EPA deems safe, members of Taylor’s Concerned Citizens group decided to take their fight to Denka’s headquarters in Tokyo.

St. John the Baptist Parish residents Robert Taylor and Lydia Gerard (left and right, respectively) with Ruhan Nagra (center), executive director of the University Network for Human Rights, in Tokyo. Photo by Barang Phuk/University Network for Human Rights.

“Denka continues to challenge the EPA’s scientific findings with its own cooked-up pseudo-science,” said Ruhan Nagra, executive director of the University Network for Human Rights, who facilitated the trip to Tokyo for Taylor and Gerard. “We felt that the necessary next step in this fight was to confront Denka at home and make sure that the Japanese media and the public start talking about what’s going on in St. John Parish.”

Nagra was part of the Stanford Human Rights Clinic team, which conducted a health survey of households within a 1.5 mile radius of the Denka plant. They surveyed more than 500 area households, gathering data on incidences of cancer, other medical diagnoses, and health problems. (The report will be released in the coming weeks.)

On June 20 Taylor and Gerard confronted Denka representatives outside the company’s annual shareholders meeting and asked point-blank why Denka treats them and their community as expendable. The pair expressed their outrage that little has changed since the company took over the plant from DuPont in 2015. At this point, the facility has been releasing chloroprene into the surrounding area for nearly 50 years.

“We know for a fact that Denka has begun to hear from its shareholders about this,” Nagra told me after their trip. She pointed out that Kyodo News, Japan’s largest news agency covered the story after Taylor and Gerard addressed Japanese media at a press conference at Japan’s Ministry of the Environment. “The trip sent a strong message to Denka that the Louisiana community is not going to stop fighting until Denka complies with EPA guidelines on chloroprene emissions,” she said.

From St. James to Washington, D.C.

Back in the U.S. capital, Lavigne and Washington attended the first-ever Congressional Convening on Environmental Justice, where policymakers, advocates, and environmental justice practitioners shared ideas about how legislation can advance the issue.

Dr. Robert Bullard speaking at the Congressional Convening on Environmental Justice.

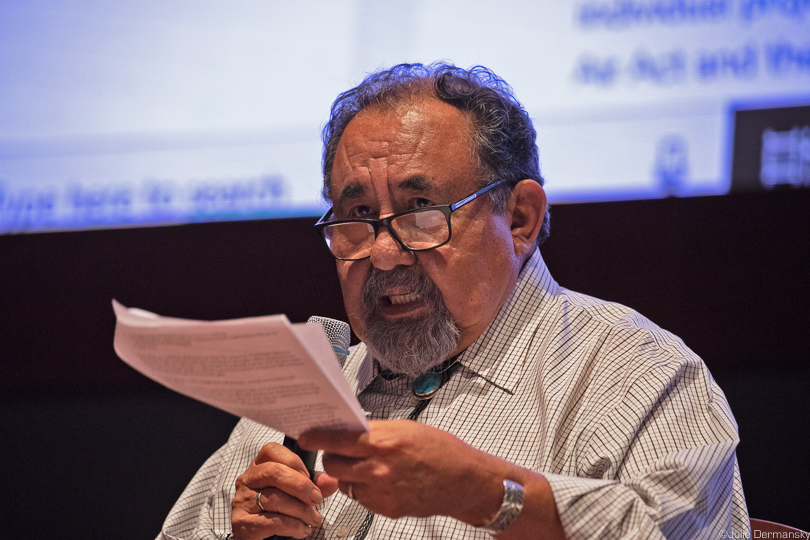

The day-long event, hosted by Natural Resources Committee Chair Raúl M. Grijalva (D-AZ) and Congressman A. Donald McEachin (D-VA), was meant to mobilize support for environmental justice and spur legislative action.

Natural Resources Committee Chair Raúl M. Grijalva (D-AZ).

Congressman A. Donald McEachin (D-VA).

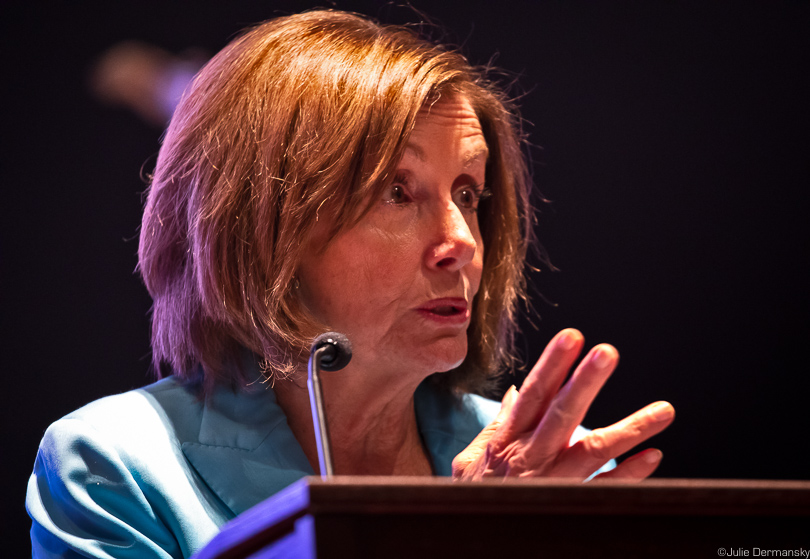

Several Democratic members of Congress took the podium, including Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi, House Majority Leader Steny Hoyer, House Energy and Commerce Committee Chair Frank Pallone Jr., and Representatives Deb Haaland, Katherine Clark, Adriano Espaillat, Nanette Barragán, and Rashida Tlaib.

Rashida Tlaib, Representative from Detroit, Michigan, described growing up thinking that asthma was normal because so many of the children in her neighborhood had it.

Nanette Barragán, Representative of California’s 44th District, talked about poor air quality in low income and minority communities.

“Environmental justice is as fundamental as it can be,” Rep. Pelosi told attendees. “It is as fundamental as the air we breathe. Every person deserves clean air.” She spoke passionately about protecting the environment, but fell short of suggesting any policy measures.

Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi speaking about environmental justice.

Rep. Hoyer closed the meeting with a focus on those most vulnerable to climate impacts — and a gaffe. “Frankly, there are some people who can insulate themselves from consequences of climate change better than some other people can. We need to make sure that we, on their behalf, focus on those who are most vulnerable,” Hoyer said. “I know many of you represent communities who are vulnerable — communities that geographically, like the 8th Ward in New Orleans, [are] very vulnerable.”

House Majority Leader Steny Hoyer speaking at the Congresional Convening on Environmental Justice.

Hoyer likely meant New Orleans’ 9th Ward, which was devastated by flooding when levees failed following Hurricane Katrina almost 15 years ago. His comments didn’t give Lavigne and Washington the sense that he was familiar with Louisiana’s current environmental justice plight, but they said they appreciated that so many officials made an appearance at the event.

The following day Lavigne and Washington had an appointment to meet with an aide of New Jersey Senator and Democratic presidential hopeful Cory Booker, who introduced the Environmental Justice Act of 2017 after his visit to St. James Parish and other environmental justice communities that year, but the bill never made it to the floor.

The women also stopped by Louisiana Senator Bill Cassidy’s office and met with one of his aides. They expressed their concerns about the impact the state’s petrochemical plant build-out would have on their health, and were promised that their message would be passed on to Sen. Cassidy.

On July 2, Lavigne and Washington received an email from Booker’s aide, Ben Hughey, who reported that he had reached out to Cassidy’s staff about the proposed Formosa chemical project the pair opposed. Sen. Cassidy’s staff told Hughey that they “would be monitoring the permitting process, but would not interfere with the LDEQ [Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality] or the EPA unless they learned that the process was awry in some way. She was pretty clear that they would be supporting the Formosa plant unless something significant changed.”

“The email didn’t surprise us,” Lavigne told me. She doesn’t understand how Sen. Cassidy, who is also a medical doctor, can support a petrochemical plant that will release chemicals harmful to human health in communities already burdened by pollution. The email inspires her to fight that much harder.

Both Lavigne and Washington will be present at the LDEQ’s July 9 public hearing on Formosa’s air quality permit to submit their comments in person — and they encourage others to do the same.

*7/9/19: Updated to correct the date of the Congressional Convening on Environmental Justice.

Main image: Barbara Washington (left) and Sharon Lavigne (right) St. James Parish residents, in Washington, D.C. Credit: All photos by Julie Dermansky for DeSmog unless otherwise indicated

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts