Albert Naquin, Chief of the Isle de Jean Charles Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw Tribe (IDJC), often loses sleep over his tribe’s fate as its historic island homeland continues to lose land at an alarming rate. His dream to relocate the tribe from Isle de Jean Charles with a federal grant has turned into a nightmare.

After helping the Louisiana Office of Community Development (OCD) win a $98 million grant from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), the Tribe no longer wants to be associated with the State’s project, which included $48 million earmarked to relocate the IDJC Tribe.

“The state hijacked the money, and now the tribe is back at square one,” Naquin explained in January after the OCD announced the purchase of 515 acres of land for the resettlement project in Schriever, Louisiana, 40 miles north of the island. He suggested that the State return the money to the federal government because the OCD’s plans did not reflect the goals and objectives the Tribe outlined in its application for the National Disaster Resilience Competition grant in the first place.

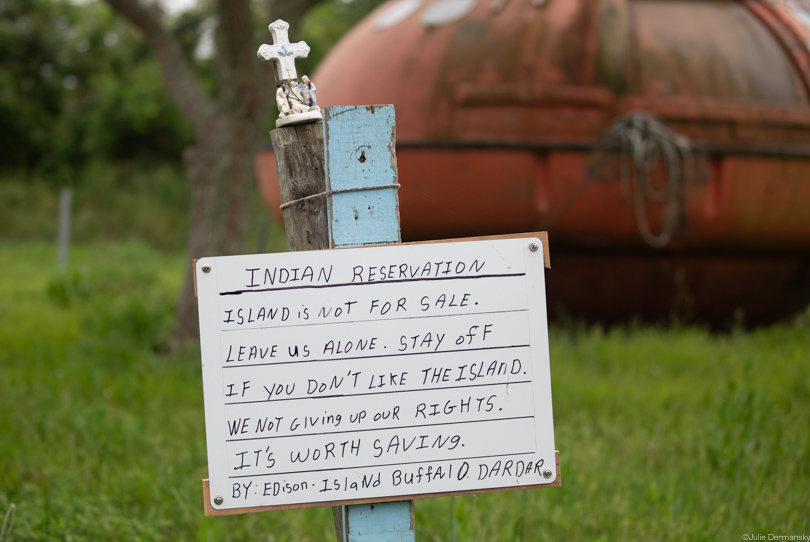

Sign on Isle de Jean Charles posted by island resident Edison Dardar, across from his home.

Edison Dardar’s residence on Isle de Jean Charles.

After Naquin’s rebuke of the State’s handling of the grant, OCD Director Pat Forbes said he still welcomed Naquin’s participation in the project, and in January met with him and other local officials to bridge the rift. Following the meeting, Naquin sent Forbes a list of the Tribe’s desired changes to the OCD plan, but the State rejected all of the requests.

Naquin described the latest version of the OCD’s Isle de Jean Charles resettlement plan as “hogwash.” “The new version of our proposal offers superficial platitudes with no substance to back anything up,” he said.

The OCD defended its resettlement project at a Houma-Terrebonne Planning Commission meeting on February 21, where it became clear that the only thing the Tribe and the State have in common is the belief that the remaining residents need to be relocated off the island.

People of the Disappearing Island

The Isle de Jean Charles, the historic homeland of the IDJC Tribe, is a shrinking island about 80 miles southwest of New Orleans, in Louisiana’s wetlands at the edge of the Gulf of Mexico. The island community is one of a growing number of coastal communities worldwide that will inevitably have to relocate due to the impacts of climate change.

Since 1955, the island has lost 98 percent of its area due to a combination of levee construction, coastal erosion, sinking land, rising seas, and damage from hurricanes worsened by climate change. Only a 320-acre strip remains today.

The estimated 19 families that remain on the island are connected to the mainland by the single Island Road, which floods frequently and is at risk of washing away altogether during extreme weather. Louisiana, which has rebuilt the road in the past, has warned it likely won’t again, which would leave the island accessible only by boat.

I tried to return to Isle de Jean Charles on April 13, but Island Road was underwater, the spring’s strong southerly winds pushing water over it. I stopped at the water’s edge to take pictures. A couple of vehicles made their way through the water, but others turned around. The perilous driving conditions were a stark reminder that the island will not be habitable much longer.

Though most of the island residents realize this reality, it is unclear how many are willing commit to the OCD resettlement project.

The OCD hasn’t revealed how many have committed to the project to date. Naquin can think of fewer than six families that might be willing to sign up for whatever the OCD offers them. Naquin says his tribe members don’t trust the State.

Land of Discontent

Growing opposition to the State plan was apparent at the February Houma-Terrebonne Regional Planning Commission meeting. Representatives from Native American Tribes, island residents, and residents who live next to the property where the state plans to develop a resettlement subdivision voiced strong objections to the project.

Isle de Jean Charles Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw Tribe’s executive secretary Chantel Comardelle at the Houma-Terrebonne Regional Planning Commission meeting

The commissioners granted an initial approval for the Louisiana Land Trust, OCD’s contractor for the project, to proceed with required studies before the permitting phase. They also told a room full of people who mostly were at the meeting to vehemently oppose the project that they will have a chance to voice their objections at a parish council meeting before a permit is granted.

“I firmly believe that the project was highjacked,” Keith Kurtz, one of the planning commissioners, said before the commission granted approval for the initial stages of developing the subdivision. Despite issues brought up by project opponents, the developer met all of the requirements to receive initial permission to develop the project further. “I really don’t know what recourse the Indians have,” he said.

A Crumbling Vision for a Tribe Reunited

The IDJC Tribe’s original plan was for a community run by the Tribe, one that would welcome previously displaced tribal members who left the island over the years as its landmass decreased, but the State’s plan doesn’t allow the Tribe control over who moves there. The OCD, instead, will turn over control of the community to a nonprofit similar to the Louisiana Land Trust, a past state partner on a post-hurricanes Katrina and Rita resettlement program. This nonprofit is already on board as the project’s developer.

The OCD will offer the first homes to current island residents who want to relocate. Future homes would be made available through special mortgages for people who had lived on the island but left in 2012, after Hurricane Isaac caused floods that increased the island’s vulnerability. The remaining plots could ultimately be purchased by anyone who can afford them, whether or not they have a connection to the island or the IDJC Tribe.

Chief August Creppel of the United Houma Nation, a Tribe with a long-standing rivalry with the IDJC Tribe, expressed solidarity with Chief Naquin. Creppel made clear that his tribe members aren’t pleased with the State’s handling of the project. “For too many years, people have been using the Indian name to get what they want, and then we find out it is not what they say it is,” Creppel told the commissioners. “We have been dealing with broken promises for hundreds of years — this is just one more promise.”

Shirell Dardar, Chief of the Grand Caillou/Dulac Band of Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw Tribe, warned that the handling of the entire project could be illegal. She suggested that it would be better for the commissioners not to vote at all. “Maybe you want to take a step back before you go any further, and take a look at all the problems,” she said.

Residents who live near the State’s proposed resettlement site also believe that Louisiana hijacked the IDJC Tribe’s plan. They complained that when they first heard about the project, they were told it was for a Native American tribe. But because the IDJC Tribe does not support the State’s plan, some Schriever residents expect that the development will become a typical low-income subdivision that will bring down their home values.

They also expressed similar doubts to those of the IDJC Tribe: Tribe members who qualify for homes, even if free, won’t be able to pay the taxes and insurance required for them to remain in good standing with the State. Those members could end up losing both their new homes and the right to move back to the island (if their old homes are still standing), leaving them homeless.

‘Utopian Disney Resort’ or ‘Dystopian Nightmare’?

While the state master plan may look like a “utopian Disney resort,” Joseph Fox, whose home is near the Schiever site, said, “In the end, I think it will turn into a dystopian nightmare.” He pointed out that the state’s plans include both a solar power farm, an agricultural farm, and a couple of parks, but offers no plan on where the money and labor will come to operate them. “This was supposed to be a project to relocate the Native people from the island, but it is no longer centered around them, so as far as I’m concerned the project is a failure.”

Mathew Sanders, resilience policy and program administrator for the OCD, defended the project. “The state feels pretty good in its moral and legal standing on this project. We feel pretty good about our position as a developer in good standing,” he said, and made it clear that the project will not be Section 8 housing, as some of the speakers fear.

One of the commissioners asked Sanders what would happen if no one from the island wants to move to the development.

“A hypothetical that won’t happen,” Sanders replied. Then, after a brief silence, he said, “Should the situation you described arise we would have to step back and reassess where we are as the State.”

Project Updates and Tribal Objections

Naquin learned that the OCD released an amendment to its resettlement plan on April 8 that is open for public comment until April 23. He was one of a handful of people who attended a sparsely attended meeting for public comment held by the OCD on April 16. He didn’t make a comment, though the Tribe will likely weigh in with a written statement.

The State’s amendment has to do with the commercial elements of the project, including the solar power farm. “None of it makes any sense,” Naquin said when I asked what he thought of the latest iteration of the plan. He fears that any members of the Tribe who sign on to the state’s project could get hurt because the Tribe has no control over any aspect of it.

One thing that irks Naquin is that the OCD frequently mentions the more than 50 visits the agency made to visit island residents during the plan’s development, but it still won’t say how many island residents are willing to move to its planned subdivision in Schriever.

“The OCD team gets a day out of the office to come to the Island, that doesn’t mean they get anything useful done,” Naquin said. He told me that some of the residents have barred the state representatives from coming on their property

Earlier this month, a woman who attends Naquin’s church said OCD representatives dropped off a flyer for parishioners. After so many visits to the island, Naquin wonders why they are still fishing for a flock to fill their planned resettlement project.

The Tribe feels so strongly opposed to the project’s current form that it asked the OCD to remove mention of the Isle de Jean Charles from the project’s name because the Tribe doesn’t want to be associated with it. The OCD rejected the request.

“Isle de Jean Charles refers to a place, and that particular place is the subject of the project,” Marvin McGraw, OCD’s communications specialist, explained to me in an email. “We expect the residents who move to the new location will want to name their new community, and we have no idea what that might be.”

I asked McGraw if the State had a commitment from Entergy, a private utility not known for solar power technology, to develop the solar component of the project. “The short answer is no,” he wrote, but the State is inquiring about Entergy’s local capacity to accept electricity from a solar farm. If it can handle it, the State will develop business agreements with the utility, but if not the State may “seek to harness solar power to offset energy costs in the community.”

I also asked if the OCD considered a back-up plan in case it doesn’t get all the permits to build the Schriever subdivision. In sum: No.

“The State fully anticipates receiving all required permits to build the new mixed-use community development for the people of Isle de Jean Charles,” McGraw wrote. “As such, it wouldn’t be appropriate to speculate on any prospective plan B.”

Though Terrebonne parish commissioners gave the OCD housing project its first approval, a new alliance is forming between Native American tribe members and Schriever residents to try to stop the development’s construction.

Naquin describes his experience working with the State as depressing.

“The outcome of this project isn’t only about our Tribe,” he told me. “Our resettlement plan, that is over a decade in the making, is supposed to be a road map for other coastal communities like ours that will have to relocate. So even if we have to walk away from the federal funds, we are determined to find another way to get it done.”

Updated 4/20/19: This story has been updated to reflect that the State of Louisiana purchased 515, not 500, acres in Schriever.

Main image: Pickup truck headed to Isle de Jean Charles on a flooded Island Road on April 13, 2019. Credit: All photos and videos by Julie Dermansky for DeSmog

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts