In the Greater Boston area, Enbridge is planning to build a controversial natural gas facility at a densely populated site which already has elevated levels of previously unreported carcinogens, documents obtained by DeSmog suggest.

Despite receiving new information indicating the current presence of these pollutants in the air around Enbridge’s proposed gas compressor station in Weymouth, the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) did not include the data in the project’s health impact assessment (HIA) which it oversaw. The assessment, which was published 10 days later, found that human health likely will not be affected by direct exposure to the station.

Shortly afterwards, the DEP permitted the facility — a 7,700 horsepower compressor station that will pump natural gas through pipelines and a key part in Enbridge’s Atlantic Bridge project to upgrade its pipeline capacity. The air quality permit, which was essentially greenlighted by the HIA’s findings, is currently under appeal before the DEP.

Air Quality Samples Sent to Rhode Island

During last year’s HIA — which was ordered by Governor Charlie Baker following a public outcry over the project — the DEP conducted air sampling to establish baseline conditions near the compressor station site. This effort combined 24-hour air sampling canisters, which were sent to a private lab for analysis during a five-week period in July and August, and sampling in intervals to record several compounds for four months.

Although the sampling found some elevated levels of the carcinogens formaldehyde and benzene, the HIA concluded that existing air quality levels were such that additional emissions from the station are not likely to affect human health through direct exposure.

Yet according to documents obtained by DeSmog through a public records request, the DEP also sent sample canisters from the compressor site during August and September to the Rhode Island Department of Public Health’s (RIDOH) air lab to “verify” its measurements during the HIA. The existence of these samples was not reported in the HIA.

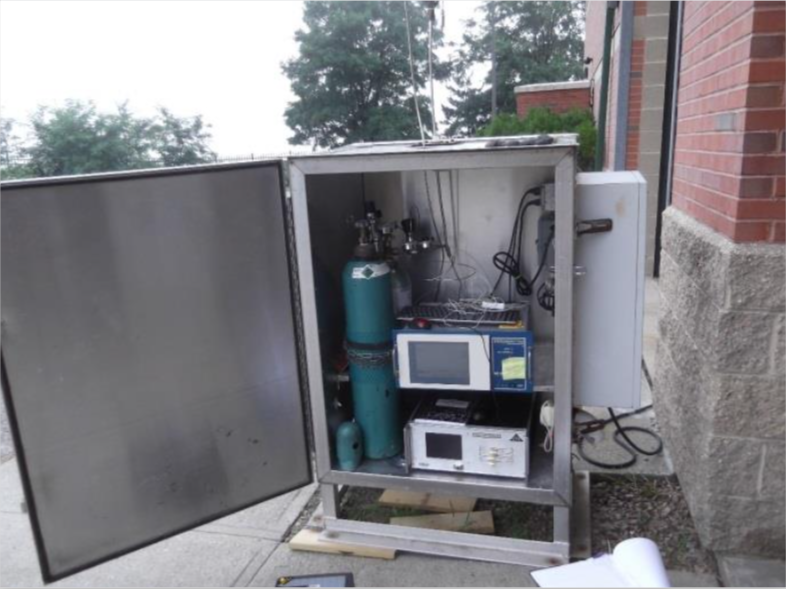

One of the air monitoring sites, at a Weymouth sewage treatment plant, in the proposed Weymouth gas compressor station’s health impact assessment. Credit: MAPC Health Impact Assessment Appendix D

On December 26 last year, 10 days before the publication of the HIA report, RIDOH sent the results back to the DEP’s air office. They indicated the presence of several volatile organic compounds (VOCs) which Massachusetts’ private lab did not test for, as it used a somewhat different target list of pollutants than RIDOH.

These included 1,3 butadiene, a highly potent carcinogen consistently associated with leukemia, which was found in levels above the Massachusetts’ allowable limits guiding health exposure risks.

Another pollutant reported at levels exceeding state limits is acrolein, a highly toxic compound that is dangerous to inhale. Recent research points to the potential carcinogenic properties of acrolein.

It’s unclear why the DEP did not ask the private lab to look for the presence of 1,3-butadiene and acrolein — especially because the HIA stated that both compounds are relevant to evaluating potential pollution from the gas compressor station.

The RIDOH lab also found elevated levels of acrylonitrile, which the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has classified as a possible carcinogen.

And while the private lab identified low levels of acetaldehyde, another compound the EPA classifies as a probable carcinogen, the RIDOH lab found acetaldehyde concentrations to be consistently above state guidelines.

The DEP confirmed it sent samples to the Rhode Island lab in an effort to ensure quality and obtain additional information, but had received the results after the HIA had been completed. Yet emails and documents obtained by DeSmog indicate the results were shared with the DEP last December — that is, before the HIA’s publication.

In addition, the DEP pointed out that the Rhode Island lab’s samples show VOC levels in Weymouth similar to the levels from Lynn and Boston at the time of sampling.

Based on the Rhode Island Department of Health air lab data, DeSmog has highlighted in yellow the compounds the Massachusetts DEP private lab did not analyze and in red the compounds that exceed state health guidelines for the proposed Weymouth compressor station site. The amounts listed are in parts per billion by volume.

Barry Keppard from the Metropolitan Area Planning Council, the organization that coordinated the HIA, said he deferred to the DEP in matters of air sampling. “For the HIA, we looked to DEP’s expertise and experience with conducting, managing the analysis, and interpretation of the air sampling,” he said, referring DeSmog to the DEP.

Ed Coletta, a DEP spokesperson, said that the state conducted a thorough assessment of air quality in this case. “While the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission has primary jurisdiction over the siting of interstate pipeline projects, Massachusetts completed a comprehensive and science-based evaluation of air quality and health impacts in advance of approving an air quality permit for a proposed natural gas compressor station in Weymouth,” he said.

“Throughout the review, the Commonwealth considered all applicable state and federal permitting requirements, and extended the permitting process by over nine months so the Metropolitan Area Planning Council could work with state agencies to analyze health and air quality conditions associated with the project,” Coletta added. “The HIA found that anticipated air emissions from the Weymouth project would meet all applicable standards and guidelines, and would not directly cause adverse health effects to the community.”

Coletta did not respond to the question of why the Rhode Island sampling efforts were not disclosed during the HIA.

With all due respect @MassGovernor you claim to understand the impacts, yet you contradicted the very Health Impact Assessment you ordered for Weymouth compressor station. You stated the HIA was a “very comprehensive review.” However page 109 of final HIA clearly states otherwise pic.twitter.com/aRREXn708V

— Wendy Cullivan (@WendyWendy48) February 6, 2019

Joseph Wendelken, an RIDOH spokesperson, says that his agency has a partnership with Massachusetts to analyze routine samples as part of the National Air Toxics Trends Station (NATTS) program.

He added that the compound list which RIDOH tested for in the Weymouth samples contains the priority compounds from the EPA’s pollution programs in addition to other compounds that the state of Rhode Island wishes to monitor.

Four Years of Struggle

The fight against the compressor station has entered into its fourth year. Led by local residents and activists from a variety of organizations, opponents have raised the alarm over health, safety, climate change, and equity concerns.

Nearly half the population living within roughly a mile of the site are considered environmental justice populations, vulnerable to disproportionate health and environmental impacts of pollution.

THREAD: Emails I obtained show Boston’s Metropolitan Area Planning Council, which conducted the Health Impact Assessment (HIA) for #Enbridge‘s planned #Weymouth compressor, was rattled by the outcry over its report, which paved the way for DEP issuing the air permit. #mapoli 1/7

— Itai Vardi (@itai_vardi) February 18, 2019

As DeSmog has reported extensively, the project has been fraught with charges of conflicts of interest and behind-the-scenes dealings between state agencies and Enbridge.

Editor’s Note: After DeSmog’s revelations, the Weymouth compressor station’s air permit is now in jeopardy.

Main image: A billboard opposing Enbridge’s proposed Weymouth gas compressor station. Credit: Fore River Residents Against the Compressor Station, used with permission

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts