Famed for its remarkable archaeological treasures from the ancient past, today Orkney is forging a low-carbon future for itself. The archipelago can point to a string of landmark achievements in developing low-carbon technology, and hasn’t been a net importer of electricity since April 2015.

Yet, this quiet renewables revolution in the far north of Scotland is under threat.

The UK’s carbon and nuclear-oriented energy regime continues to punish Orkney for its clean energy bounty: Community owned wind turbines often sit idle due to a lack of grid infrastructure, the islands have the highest fuel poverty rate in the UK, and a regressive charging regime sees producers pay a premium to send their electricity south.

The ‘Energy Islands’

Set in the north-west corner of the Orkney archipelago, the island of Westray (population: 600) was an early-starter in making a bid for a sustainable future based on the fierce elements that have shaped ways of life in this part of the word for millennia.

This historic shift began in 1998 when, with the traditional whitefish industry in crisis, the islanders on Westray held a conference to determine what might be done to mitigate outward migration from the island in the wake of job losses.

The result was the foundation of the Westray Development Trust, formed with the goal of making the island entirely powered by renewable energy. In 2005, they took the audacious step of purchasing an electric vehicle for community use, well before manufacturers were offering off-the-shelf models.

“The community recognised early on that something needed to be done if a healthy, thriving population was going to remain on the island. There needed to be a way to bring sustainable jobs and infrastructure to the island to reverse this downward trend,” says Clare Lucas, who works at Westray Development Trust.

The island’s 900 kilowatt wind turbine generates around half a million pounds of revenue each year for community projects. Throughout Orkney, other communities have gone on to develop their own turbine-powered trusts based on this model.

A wind turbine in Orkney. Credit: Pixabay CC0

Undersea electricity cable connecting Orkney to the mainland © Laura Watts

The story of Westray Development Trust is just one strand in a rich tapestry of stories about Orkney’s remarkable renewables revolution by ethnographer, poet and writer Laura Watts. Energy at the End of the World is the result of a 10 year study, and offers an original perspective on how Orkney has changed in that crucial decade.

In this account, these “Energy Islands” are a place where renewable power, a constant presence amongst the gale force winds and raging seas that incessantly batter the coastline, is viewed less as a commodity and more like a fundamental part of day-to-day life.

“A low-carbon renewable energy future, which is much talked about elsewhere, is coming early to Orkney,” notes Watts.

But in addition to being a study of the economic and scientific processes involved in making this new future, her work is also deeply rooted in the islands’ past, woven, like the old Norse sagas, from fragments of culture, fable, myth.

There is an inherently heroic quality to the story of a rural, plucky, self-reliant place trying to make a distinctive mark, despite frequent intransigence on the part of a UK economy and government still hooked on fossil-fuels. But Orkney has long since surpassed the limitations of what fierce independent localism can achieve.

Ambitions curtailed

Orkney boasts a string of notable firsts — the first smart grid, the first grid battery, the first community owned wind turbine, in addition to the highest number of electric vehicles per head of population in Scotland. There is also an impressive energy knowledge base on the islands, embodied in the Orkney Renewable Energy Forum, which meets every month.

But this string of achievements pales in comparison with future potential. The unique geographical position of Orkney at the meeting point of the North Atlantic and the North Sea means that there is an estimated marine energy capacity amounting to several gigawatts: if fully exploited, energy generated from around the islands’ coastline would be on a par with one of the UK’s large nuclear reactors.

Despite the burgeoning sector creating hundreds of local jobs and delivering millions in revenues and investment, the islands continue to be viewed as a peripheral anomaly in the current UK energy system: a system that makes Orkney pay for its excess of renewable energy.

The islands currently generate around 120 percent of their electricity needs. But rather than being rewarded for this energy surplus, the current set-up sees the islands penalised for creating too much clean power.

At the root of the problem is the sub-sea cable built to link Orkney to a highly centralised, carbon and nuclear-oriented national grid, which simply isn’t up to the job. There have been a plethora of calls for additional capacity, with OFGEM and Scottish and Southern Electricity Networks (SSEN) currently negotiating terms for a £260 million, 220 megawatt, high-voltage link to be completed by 2023.

As Watt’s notes in her study, the “exchange-rate” for energy prices is “inverted.” At present the constantly shifting rate can see generators on Orkney charged as much as £40 or £100 per kilowatt hour.

Added to this, community owned wind turbines have to be turned off or “curtailed” when the grid reaches capacity, directly depriving some of the most isolated areas of potentially transformative funds.

Aerial view of EMEC tidal test site at the Fall of Warness © Aquatera

Caldale substation and hydrogen plant © Orkney Sky Cam

Many islanders are incensed at the slow pace of change, when contrasted to the rapid innovation taking place daily around their coastline.

Based in an old high-school, the European Marine Energy Centre (EMEC) is the preeminent global testbed for marine renewables, drawing the interest of an array of global investors — including Silicon Valley giants like Microsoft.

However, despite its success (since 2003, 31 devices from 11 different countries have undergone testing at the site) the inadequate grid infrastructure poses a potential threat to the viability of EMEC.

“It’s definitely holding us back,” says Neil Kermode, Managing Director of EMEC.

“At the moment, we’re the only place doing this anywhere in the world. But there are other places lining up to do this … the industry that we have got here and we’ve built up here is absolutely at risk and will go overseas if they get better from somewhere else.”

Energy inequality

The lack of strategic vision required to fix Orkney’s energy infrastructure is an issue of social justice, too. Despite an abundance of energy production and a willingness by the islanders to push innovation to its limits, the islands have the highest fuel poverty rate in the UK.

The factors behind this, common throughout rural Scotland but especially acute in Orkney, range from a lack of gas infrastructure for heating, to high fuel costs, to the nature of the housing stock itself — which in places like Westray consists mainly of old stone built dwellings that are often uninsulated.

The still smaller island of Rousay (population: 216) is trying to tackle the twin issue of community turbine curtailment and fuel poverty with a Smart Heat Project, using a variant of “Total Heat Total Control” already deployed by providers to manage demand during peak times.

The aim is simple and compelling: “instead of turning the turbine off, we want to divert that lost power and use it locally,” says the island development trust.

Energy inequality within the islands is a potent issue, too.

Robert Leslie, Energy Officer at Orkney Housing Association, describes the gap between ‘energy rich’ Orcadians — those with the means to invest their own capital in personally owned assets (such as a small turbine, solar panel, or electric vehicle) and the majority of ‘energy poor’ islanders. The latter pay exorbitant prices for electric heating and at the petrol pump.

Of the housing association’s 772 tenants, 66 percent are in fuel poverty, with 22 percent in “extreme fuel poverty” where more than 20 percent of their income is spent on fuel costs.

For Leslie, this problem is captured in a single anecdote:

“A couple of years ago, I heard the story of a farmer who noticed that gaps were opening in the wood panelling in his hallway due to the fact he was heating it to such a degree, unable to put the electricity generated by his wind turbine into the grid.”

“At the same time, a mile from that farmer’s house on the edge of Kirkwall, I could visit a tenant who worried how many hot meals she could serve her children during the week as she watched the money count down on her prepayment electricity meter.”

“The gap between Orkney’s energy rich and energy poor might be small in distance, but it is huge in resource,” he explains.

Poverty and Scottish nationalism

Orcadians might not be taking to the streets, as the Gilet Jaunes did, to protest at the iniquities present in the shift to low-carbon energy. But the question of who will be carried along and who will be left behind on the Energy Islands cannot be answered in isolation.

Orkney Islands Council, with the smallest population of any local authority in Scotland, lacks the scale and, particularly in a time of austerity, the risk-bearing capacity, to take decisive interventionist steps to fix the situation.

At a Scottish level the changing picture is not encouraging.

Our Power, a Scottish government supported not-for-profit retail energy supplier, folded in January 2019. After only a few years in business, its attempt to reduce fuel poverty by brokering lower prices for social tenants, including many in Orkney, was stymied by a retail energy market that props up the big six and has seen numerous start-ups go to the wall.

The current Scottish National Party (SNP) administration at Holyrood is committed to delivering a Scottish National Energy Company (SNEC) during the current term of the Scottish Parliament, but the nature of this new public entity is already a matter of fierce debate.

Scottish nationalism has often mobilised around the issue of injustice of fuel poverty in an energy rich nation.

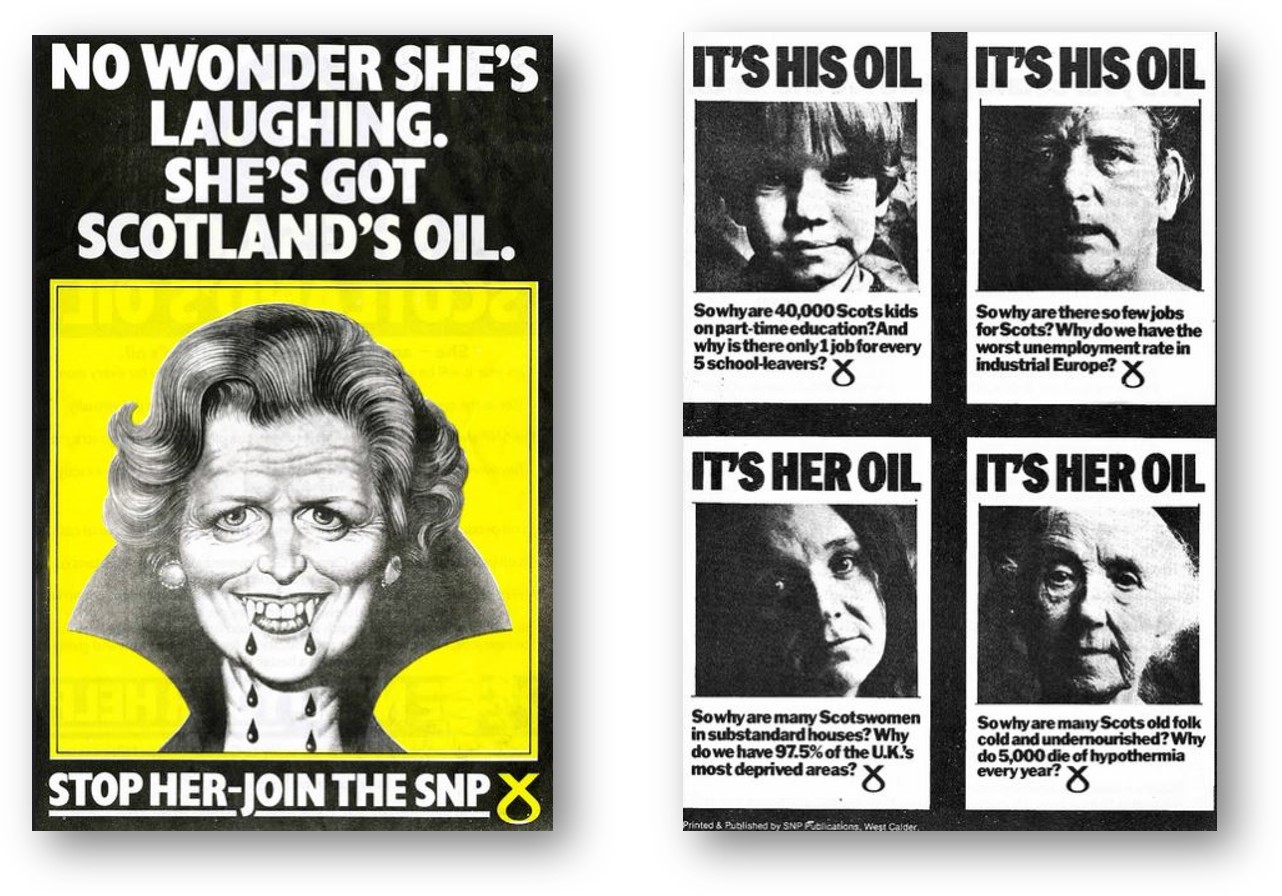

Riding the wave of a previous energy revolution, the SNP’s iconic “Scotland’s Oil” campaign, which led to the party’s first electoral breakthroughs in 1974, featured text below the image of a Scottish pensioner asking, “why are so many Scots old folk cold and undernourished? Why do 5,000 die of hypothermia every year?”

SNP leaflets promoting the idea of ‘Scotland’s oil’ © Scottish Political Archive, University of Stirling

With Age Scotland reporting that 60 percent of single-pensioner households in Scotland struggle with energy bills, the issue remains a national controversy.

The nature of how the SNEC is constituted will be crucial. A recently published report by left-leaning thinktank Common Weal called on the Scottish Government to embrace a model that moves beyond the retail market and includes ownership of generation assets, too.

For the report’s lead author, Dr Keith Baker of Glasgow Caledonian University, this will be the essential determinant of whether an SNEC can tackle energy injustice in Scotland:

“At the end of the day Our Power was still a retail energy company. Therefore they were always going to be susceptible to the kinds of things that tend to bring retail energy companies down … that’s one of the reasons that we pushed so hard for the National Energy Company to own generation assets.”

Slamming a lack of strategic thinking on the part of the Scottish Government, Baker contends that an SNEC would be uniquely well placed to front the kind of investment in infrastructure required in Orkney:

“The real value here is in generation assets and in supply assets and in doing the sorts of projects that are not going to have very high returns but are going to benefit a lot of people in a lot more ways — the co-benefits of tackling fuel poverty and job creation, and sustainable fuel supply chains — they need to be thinking at that level. Which again is why we need a strategic approach.”

Orkney’s electricity export log-jam is a by-product of this lack of long-term thinking on the part of regulators and policymakers. This is why OFGEM and SSEN continue to debate the immediate return required to justify the additional connection, despite Orkney’s marine energy capacity equating to around 10 percent of the UK’s current electricity demand.

Neil Kermode of EMEC points out that this debate has been going on for twenty years. It is a symptom, he believes, of a systemic failure:

“Frankly it’s a function of the privatised element of the process, which requires people to have a business case for doing things, as opposed to there being an element of vision.”

In response to such frustrations, and a system that seems intent on keeping Orkney on the margins, island resourcefulness attempts to fill the gap.

The profusion of electric vehicles offers a DIY method of offloading additional grid capacity, acting as multiple mobile grid batteries. There’s also a plan, with a pilot already underway, to re-fit Orkney Island Council’s ferry fleet to be powered by locally produced hydrogen — another notable first.

Kermode, originally from Bournemouth, sees a unique factor in Orkney that underpins this willingness to innovate:

“There’s something really powerful about an island: you know who’s there. You can pretty quickly get around and go ‘right, we’re thinking of doing this, has anyone got a problem with this? If you have, then just say so’,” he explains.

“In a landscape like Orkney … it’s really hard to keep a secret. So you don’t bother. So you tend to be honest and open about stuff … it’s quite a contributive culture … That sort of culture pervades what goes on in Orkney and has done for generations.”

EMEC Billia test site in Orkney © Colin Keldie

Billia Croo waves © Rob Ionides

Island independence

In one of the last poems published before his death, Orkney’s greatest bard, George Mackay Brown, wrote to an imaginary Orcadian poet in 2093. In verse rich with the references to the different cultures that have inhabited Orkney, he explored the commonalities across time, including the role of the sea:

“We wear the sea like a coat/We have salt for marrow.”

Explaining the significance of marine energy to UK policy makers, unfamiliar with the far-flung islands, is bound to be challenging. But perhaps Orkney’s insistence on occupying the leading edge of energy innovation, rather than settling for a peripheral role, points to a whole new paradigm for a post-carbon economy.

Carbon-based capitalism concentrated itself in large cities where cheap workforces were easier to come by and economies of scale, fed by centralised distribution networks, kept costs down. Perhaps its successor is already taking root in places not hemmed-in by the assumptions of what has gone before.

Writing against the bleak backdrop of the late 1930s, another Orkney bard, the novelist Eric Linklater, observed:

“Have I said we are an independent people? It is one of the blessings of a small land. For freedom of opinion, even of action, is still permissible in small places.”

By shaping an energy revolution on its own terms, Orkney has shown that it doesn’t require permission to forge a new future. It simply needs the rest of the UK, with its ageing 20th century energy system, to stop living in the past.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts