The UK government has been boasting about its global climate leadership both at home and on the world stage for more than 25 years. But, for the first time, a trove of confidential government documents recently made public by the National Archives reveals how the Conservative government of John Major worked internally to cement the image of the UK as a global climate leader.

The documents focus on the UK’s environmental policy in the years following the 1992 Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. They reveal the Major government’s desire to be the first to announce climate action and secure the UK’s position as a leader on the issue despite internal concerns that its climate plan was “too bland” and lacked ambition.

Speaking to DeSmog UK, Michael Howard, former leader of the Conservative Party and Secretary of State for the Environment from 1992 to 1993, said the UK deserved its leader image.

“At the time, we did see ourselves in that way and we did speak in those terms,” he said. “If you look at the extent of what we have done over the years, we are entitled to be seen as a world leader on these issues.”

Reflecting on 25 years of climate policy, Paul McNamee, head of politics at the environmental think tank Green Alliance, warned that while the UK “can still be seen as a global leader on climate, it is increasingly reliant on past actions to hold this title”.

“The Climate Change Act has kept the government on the right track but on current performance it is not delivering on even its current targets, never mind future ones,” he said.

Inside John Major’s government

The documents span over a short period between 2 December 1993 and 31 January 1994. They include ministerial briefings and notes, letters and confidential exchanges between Prime Minister Major’s office, his private secretary, advisors and ministers.

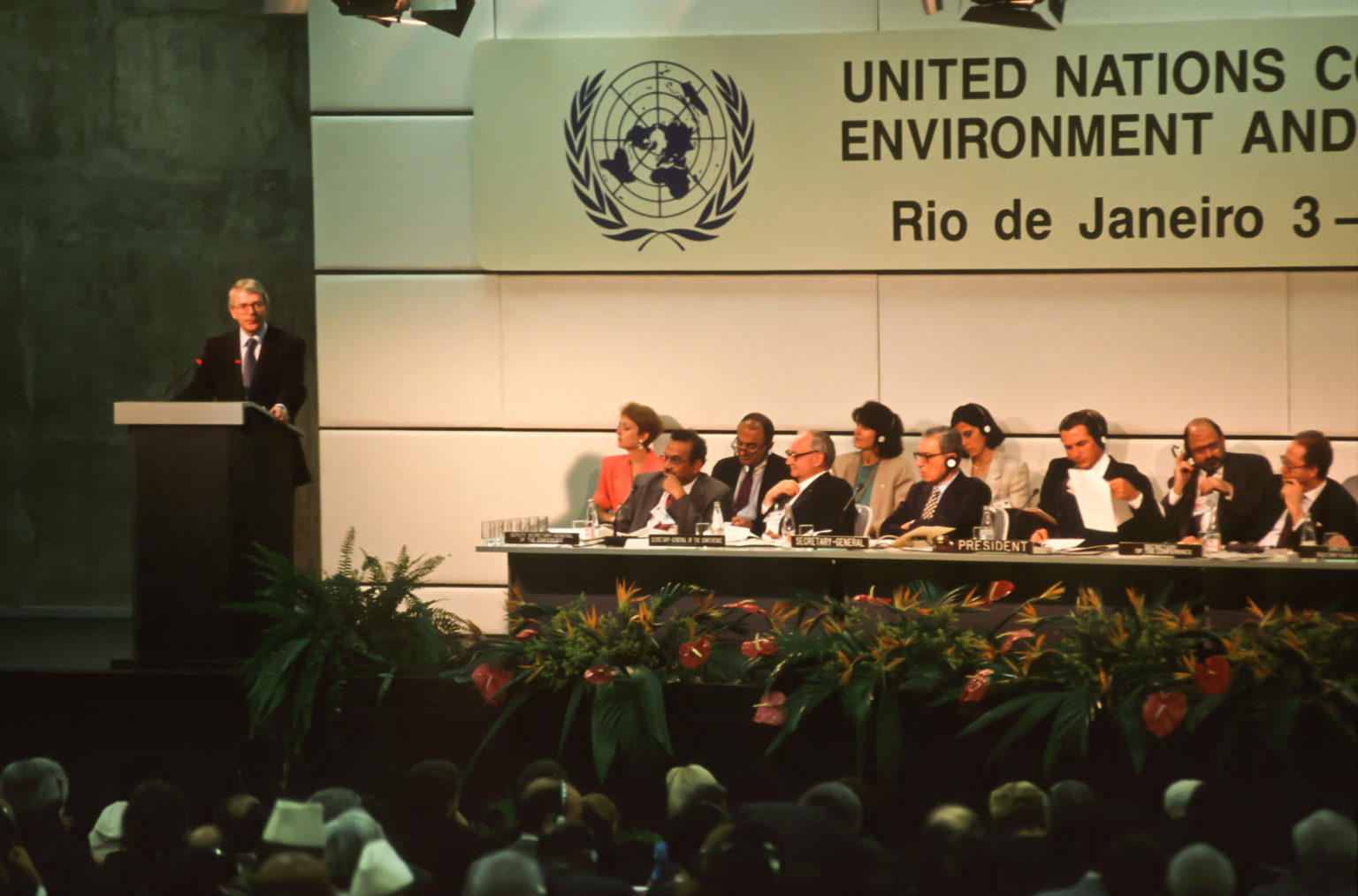

At the landmark UN summit in Rio in 1992, countries committed to stabilise greenhouse gas emissions at 1990 levels by 2000. The summit showed willingness for a global and cooperative response to human activities’ impact on climate change and marked a shift in global attitude towards the environment.

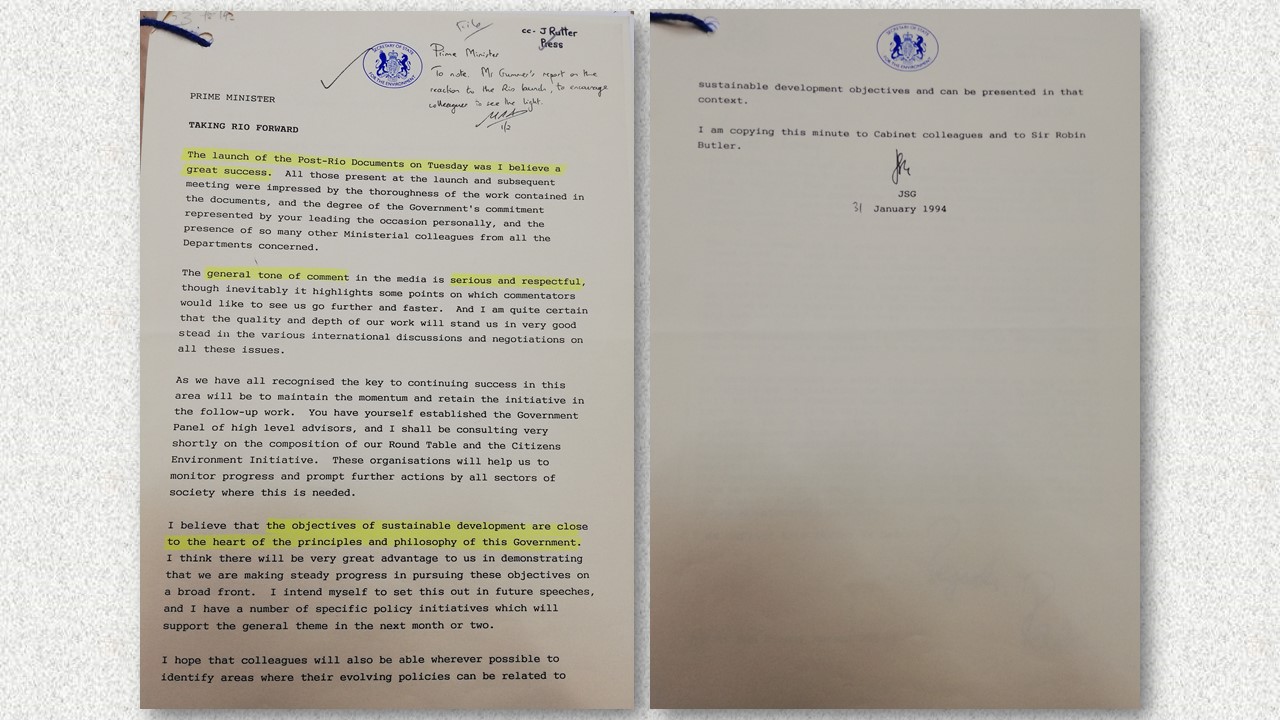

In January 1994, the UK became one of the first countries in the world to introduce a national “Sustainable Development Strategy” to meet its commitment under the Rio Convention. At the time, it described the launch of its plan as a “great success” that was covered by the media with a “serious and respectful” tone and left those attending the launch “impressed by the thoroughness of the work contained in the documents”.

The government hailed itself a “leader” on the issue for being “the first country in the world to demonstrate under the Convention” how it would reduce emissions.

But behind the scenes, the government was concerned the strategy was “too bland” and that internal department brokerings had watered down the text to the point it “lack[ed] specific commitment to action”.

1994: ‘The first to lead’

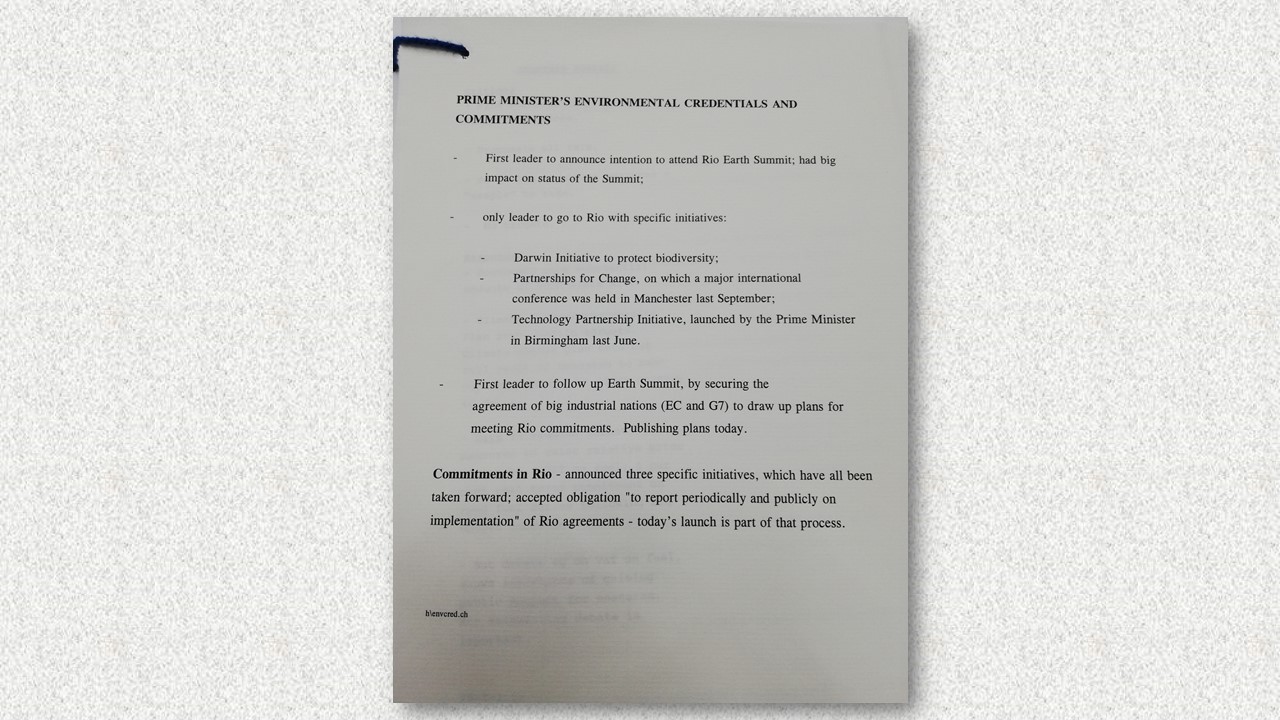

The launch of the UK Sustainable Development Strategy took place on 25 January 1994 and was aimed to showcase Prime Minister Major as a climate leader and boost his “environmental credential and commitments”.

In a briefing anticipating media coverage of the event, ministers and advisers were urged to emphasise the fact Major had been “the first leader” to announce his intention to attend the Rio summit, the “only leader to go to Rio with specific initiatives” and “the first leader to follow-up” on the summit by securing agreement from the European Commission and the G7 to fulfil their climate commitments.

For the UK government, being first was proof of leadership and commitment.

Major’s direct involvement in the launch of the strategy was repeatedly discussed ahead of the event. Mark Adams, the Prime Minister’s private secretary, urged Major in a letter to emphasise his “continued personal interest and involvement in environmental issues”, first displayed by his participation at the Rio summit.

But according to Jill Rutter, a former advisor to John Major and now programme director at think tank the Institute for Government, Major’s alleged commitment to the issue was largely exaggerated.

Rutter said the UK was “very proud” of the fact Margaret Thatcher had been the first world leader to identify climate change as a major risk in a 1989 speech to the UN. “It [climate change] was probably not John Major’s top priority but it felt like an important Thatcher legacy and that’s why the UK wanted to embrace an activist position,” she said.

Rutter added that Major “did not want to put time and effort” working on the Sustainable Development Strategy and the issue was passed on to ministers and “very activist officials in the department for the environment, who were findings ways to push the agenda forward”.

Discourse of urgency

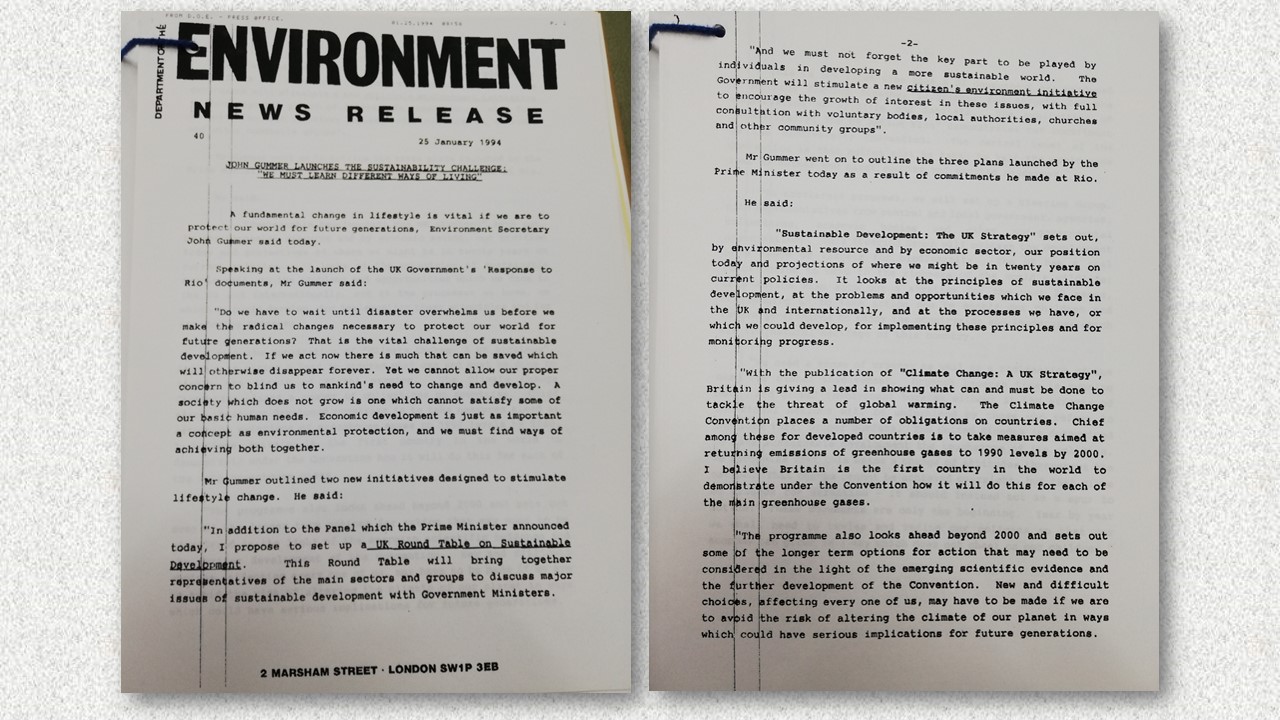

Launching the Sustainable Development Strategy, then Environment Secretary John Gummer, now known as Lord Deben and the chair of the Committee on Climate Change, warned in a speech that fundamental changes in lifestyle were vital to respond to the urgency of tackling climate change, adding that “new and difficult choices may have to be made”.

Using language that still resonates today, Gummer said: “Do we have to wait until disaster overwhelm us before we make the radical changes necessary to protect our world for future generations? If we act now there is much that can be saved which will otherwise disappear forever.”

Gummer emphasised that the “radical changes” required could still go hand in hand with economic growth.

“Economic development is just as important a concept as environmental protection, and we must find ways of achieving both,” he said, setting out the government’s intention to “find ways of breaking the link between economic development and increasing emissions of greenhouse gases”.

But advisor Rutter told DeSmog UK that officials and ministers long debated internally whether it was sensible to impose climate measures before any other powerful economies. Rutter said she remembered rows between the treasury and the Department for the Environment, which was keen to promote “first mover’s advantage”.

Rutter said that tensions and efforts to reconcile the economy and the environment continue to dominate today and that successive governments have been keen to take climate measures that provide a market advantage.

But for Sam Richards, Director of the Conservative Environment Network (CEN), while the idea of decoupling economic growth from increasing emissions remains at the heart of environmental debates today, “when we talk about the low-carbon economy we are just talking about the economy”.

Richards insisted it remains “really important that we speak about the successes of the green economy” and how climate action can contribute to economic growth.

“What would have been considered radical in 1994 would now be common sense and a reality”, he added. “Part of it is that the science of climate change has become so much clearer and we are seeing its effects in our world around us. We are no longer making predictions about possible futures, we are living it.”

Championing the idea that climate action is good for the economy since the 1990s, Lord Howard said that while this was once seen as radical, the UK “demonstrated that it is possible to grow your economy while taking action to deal with climate change”.

Reflecting on the UK’s climate policy since the Rio summit, Lord Howard said: “There was a sense that the world as a whole was taking a challenge and the Rio summit was the first step on that path,” adding “intermittent steps taken since have not been enough.”

Optimistic that more will be done to respond to the threats of climate change, Howard said the UK “should be able to continue to play a leading role”.

Until June last year, Howard was the chairman of Soma Oil and Gas, an oil exploration company in Somalia. He also sits on the advisory board of thinktank, the Energy and Climate Intelligence Unit.

A place on the world stage

Following the launch of the UK’s Sustainable Development Strategy, Environment Secretary Gummer wrote to the Prime Minister describing the launch as “a great success” that showcased “the degree of the Government’s commitment” represented by Major “leading the occasion personally”.

“And I am quite certain that the quality and depth of our work will stand us in very good stead in the various international discussions and negotiations on all these issues. I think there will be very great advantage to us in demonstrating that we are making steady progress in pursuing these objectives on a broad front,” he said.

For the UK government, the strategy’s early publication was also a way to set the country ahead of the European Union and the US.

In a letter to Major on 2 December 1993, Rutter wrote that the UK ratification of the Climate Change Convention set-out in Rio “will put us ahead of the rest of the EC [European Commission]”.

The US position on climate change was also closely watched by the UK — not least after Lord Howard went to Washington D.C. in the weeks preceding the Rio summit to convince President George H W Bush to attend.

Briefing notes ahead of the launch claim that although the US had made draft plans under the Rio Convention, the UK was the first to publish its strategy.

But the government’s benchmarking against the US went even further.

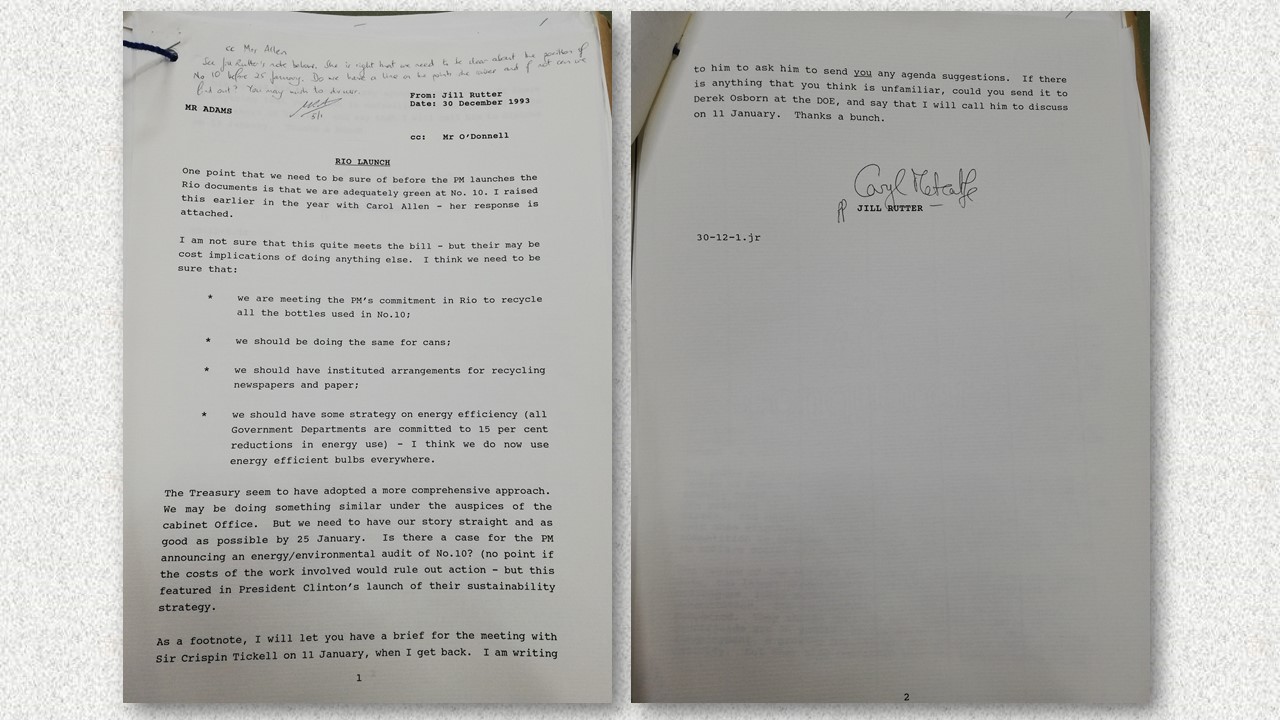

On 30 December 1993, advisor Rutter sent a letter to the Prime Minister’s private secretary Adams urging him to ensure that Number 10 was “adequately green” before the launch of the Sustainable Development Strategy in order to “have our story straight and as good as possible”.

The note warned Number 10 to ensure all recycling targets announced by the Prime Minister in Rio were being met and suggested the announcement of an “environment audit of Number 10”, mirroring what she said “featured in [US] President Clinton’s launch of their sustainability strategy”.

More than 25 years on from the Rio summit, Green Alliance’s McNamee told DeSmog UK that hosting the UN climate talks in 2020 could help the UK “garner even more influence” on the issue.

“It is the next opportunity for the UK to set a standard like it did in Rio, delivering global leadership based on ambitious domestic delivery,” he said.

‘Bland and indigestible stuff that lack specific commitment to action’

Despite praise, internally, the government knew that the 1994 Sustainable Development Strategy was far behind the level of action needed to tackle the issue.

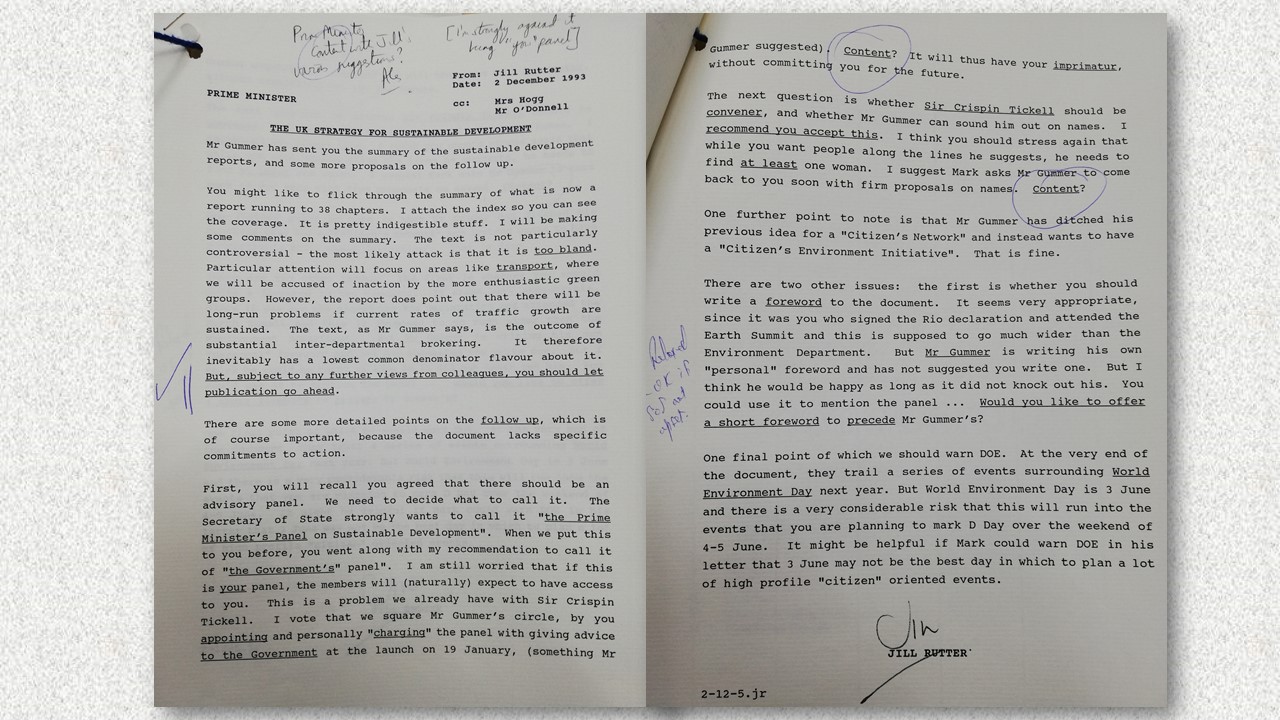

In a letter to Major on 2 December 1993, advisor Rutter suggested the Prime Minister take a look at the final strategy draft.

“It is pretty indigestible stuff,” Rutter warned.

Describing the text as “not particularly controversial”, she added that “the most likely attack is that it is too bland” and that “the document lacks specific commitment to action”.

On transport, one of the strategy’s key focuses, Rutter said the government “will be accused of inaction by the most enthusiastic green groups” despite the fact “the report does point out that there will be long-run problems if current rates of traffic growth are sustained”.

In another letter to Major on the same day, Rutter explained that the government’s pledge to increase road fuel duties by at least five percent on average “will deliver much of the [emissions] savings” with the rest being voluntary measures”.

Speaking in 2019, Rutter said the government was seeking to “do things that they would do anyways” and “nobody felt there was that much political space for measures that would cost people money”.

“It is easier to set far away targets than take short-term measures that are not underpinned by early ambitious action,” she added, when prompted about the Climate Change Act and the UK seeking advice to achieve “net zero” emissions.

Departmental brokering

In 1994, Rutter warned Major that the final text for the Sustainable Development Strategy was “the outcome of substantial inter-departmental brokering” and “therefore inevitably has the lowest common denominator flavour about it”.

“But, subject to any other views from colleagues” the text should be published, she concluded.

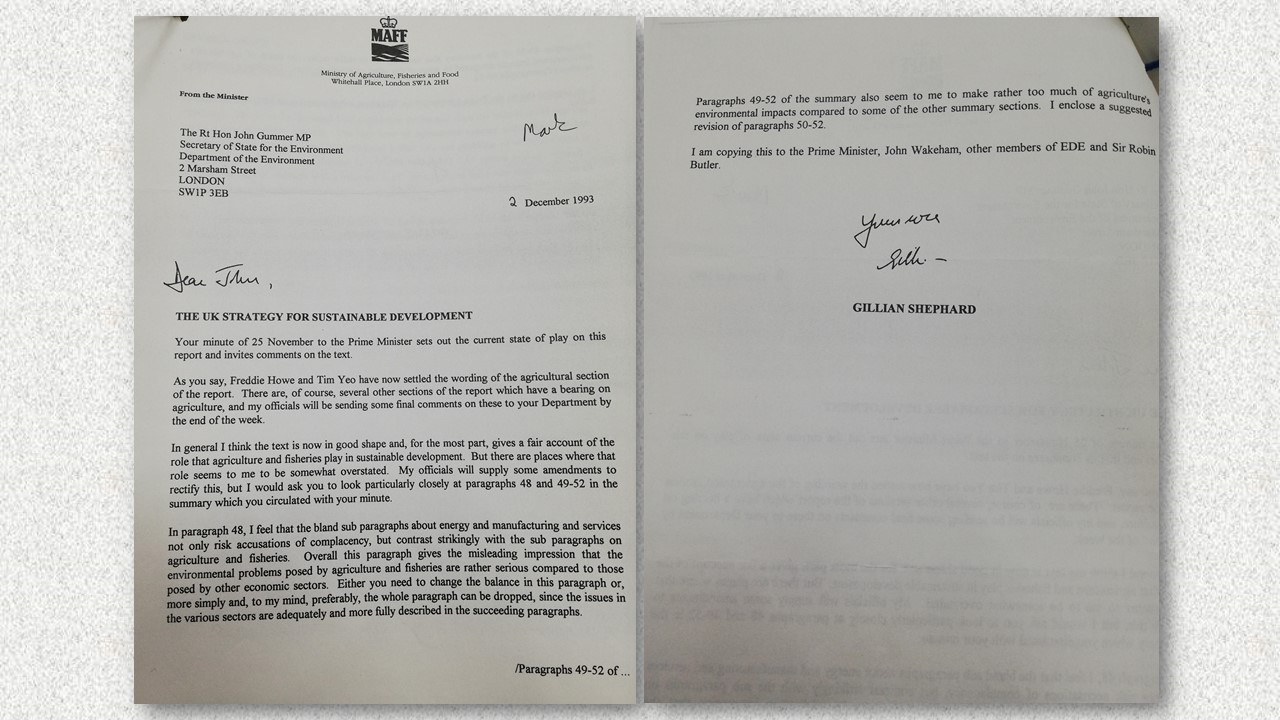

In a letter dated 2 December 1993, Minister of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food Gillian Shephard, urged Environment Secretary Gummer to consider amendments to the draft. Shephard argued that in some places “the role that agriculture and fisheries play in sustainable development seems to me somewhat overstated”. Instead, she called for more “balance” in the share of environmental responsibility bared by individual sectors.

“In paragraph 48,” she wrote, “I feel that the bland sub paragraph about energy and manufacturing services not only risk accusations of complacency but contrast strikingly with the sub paragraphs on agriculture and fisheries. Overall, this paragraph gives the misleading impression that the environmental problems posed by agriculture and fisheries are rather serious compared to those by other economic sectors.”

Rutter said the department for the environment was “frustrated” in its attempt to get cross-government action and said she remembered “big rows” over the Department for Agriculture and the Department for Transport’s reluctance to get involved.

For McNamee, of Green Alliance, this reluctance from some government departments to take robust climate action is still relevant today. He warned that while the UK has been world-leading on coal phase-out and wind power roll-out, these achievements have been delivered by the former Department for Energy and Climate Change (DECC) and the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS).

“New challenges such as electric vehicles and housing efficiency have to be delivered by other departments that are not currently facing up to them,” he said, adding that reshaping the food and farming system post-Brexit would give the UK a “unique opportunity to set a global standard for decarbonising agriculture and land use” and “be a global leader”.

Image credit: John major delivering his speech at the Earth Summit in Rio in 1992. Sue Cunningham Photographic / Alamy Stock Photo

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts