“You don’t give a shit about brown and black people,” Louisiana activist Cherri Foytlin told government officials during a heated public permit hearing for a proposed plastics plant in St. James Parish. The parish is a predominately African-American community on the banks of the Mississippi River and has undergone rapid industrialization in recent years.

“This is a dog-and-pony show and everybody in this room knows it,” she asserted, after the hearing officer cut off the sound system while Foytlin was giving her public comments. The officer, O.C. Smith, attorney for the Louisiana Office of Coastal Management, did this declaring that the hearing was no longer on the record.

About 40 people attended the December 6 hearing in Valcherie, an unincorporated community in St. James Parish, Louisiana, located 50 miles west of New Orleans. It was held by representatives from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ), and the Louisiana Department of Natural Resources (DNR).

These agencies are considering whether to grant wetlands usage permits and water quality certification for a $9.4 billion chemical plant proposed by Taiwanese industrial giant Formosa Petrochemical Corp., which needs these approvals before it can break ground.

‘The Sunshine Project’ That Would Make Plastics

The proposed chemical complex, called the Sunshine Project (ostensibly due to its proximity to the Sunshine Bridge), would be built on 1,600 acres along the west bank of St. James Parish and would operate continuously, day and night, not far from African-American communities.

The Baton Rouge Advocate reported that the complex would release considerable volumes of air pollutants, ranging from volatile organic compounds and nitrogen oxides (smog precursors) to formaldehyde and other carcinogens, according to the company’s permit application.

Before the community knew about the proposed project, the Taiwanese company was welcomed by Gov. John Bel Edwards and Louisiana’s economic development agency. Don Pierson, the agency’s secretary, told the Baton Rouge Advocate that state and local officials offered an estimated $1.5 billion in incentives to Formosa to bring the plastics complex to this location along the Mississippi River.

St. James Parish is located along a stretch of Mississippi River between New Orleans and Baton Rouge known as the “Petrochemical Corridor” to industry supporters and “Cancer Alley” to locals and environmentalists because it is lined with chemical plants and refineries known to emit cancer-causing emissions.

The early December permit hearing lasted over three hours, with most of that time filled with testimony from local residents and environmental and civil rights activists who vehemently opposed the plant. Other than a company representative, only one other person spoke in support of the proposed plastics facility.

Janile Parks, representative of Formosa, speaking at a public permit hearing.

Janile Parks, director of community and government relations for the plant, was the first to speak at the hearing. She went over the ways the company intended to be a good neighbor, from helping develop a much-needed emergency evacuation route for the residents of St. James to job training for community members who might want to work at the plant.

“As part of our ‘Think Local’ policy and our commitment to deliver environmental benefits to all stakeholders, we will soon start a community beautification project that involves improvements to Welcome Park in District 5 to provide children a safe place to play and a recreational area for our neighbors to enjoy,” Parks said.

She touted the jobs the project would bring and explained how the plant’s production of ethylene and other petrochemicals would be used to make products society demands, including plastic bottles, artificial turf, and polyester clothing.

Cancer Alley as a ‘Sacrifice Zone’

Sharon Lavigne, a St. James resident and director of RISE St. James, a recently formed community organization, pointed out that the promised improvements to neighborhood parks and schools are of little use when nearby industrial pollution already threatens community members’ lives.

In a letter to the editor of the Baton Rouge Advocate, Lavigne wrote: “Title VI of the Civil Rights Act and Article IX of the Louisiana Constitution are supposed to protect Black communities from this type of environmental racism. They haven’t in Cancer Alley.”

Sharon Lavigne, director of RISE St. James, a newly created community group.

Meg Logue,* from the environmental advocacy group 350 New Orleans, pleaded with hearing officers to visit with community members as she has and listen to the losses their community has already faced. “Make no mistake, continued petrochemical development is a death sentence for the people of St. James,” she said.

Opponents to the project made the case that the state is turning communities in Cancer Alley into a sacrifice zone.

Already home to hundreds of existing chemical plants and refineries, Cancer Alley has several other proposed projects underway, including Yuhuang Chemical’s $1.85 billion methanol facility in St. James Parish and a $1.25 billion chemical complex proposed by the Chinese chemical firm Wanhua, which would build its facility across the river from where Formosa’s Sunshine Project would be built.

Meg Logue with 350 New Orleans speaking against Formosa’s proposed plant.

Many of the speakers, including Scott Eustis, a coastal wetland specialist for Gulf Restoration Network (GRN) asked for an environmental impact statement and an environmental justice analysis. The public comments submitted on behalf of GRN challenged Formosa to consider sites outside of African-American communities.

“Failure to even consider alternative sites that do not disproportionately affect minority or native populations would seem to violate title VI protections,” GRN wrote.

Scott Eustis speaking on behalf of the Gulf Restoration Network against the proposed plant.

A written comment, submitted by the Louisiana Environmental Action Network, requested that the permits be denied and/or suspended until the proposed project addresses the environmental justice communities “in relation to the negative social economic, health and environmental impacts to be associated with the construction and operation.”

The Role of Race in Government Decisions

I asked the three permitting agencies that held the hearing if race will play a role in the decision-making process for Formosa’s proposal.

In an email, Patrick Courreges, a spokesperson for DNR, wrote: “No, OCM [Office of Coastal Management, which is part of DNR] does not factor any questions of race into making a permit decision.”

He added, “In considering Coastal Use Permit applications, the OCM looks at a range of issues, but the primary focus of the program is impacts of the construction and operation of a project on coastal systems such as wetlands and water, particularly such things as biological habitats, alterations of sediment transport, water quality, and coastal erosion.”

Race also will not play a role in DEQ’s decision when considering granting a water quality certification, according to Gregory Langley, a spokesperson for DEQ.

But he added that environmental justice issues do play a role when the agency considers permits, and this project will need an air quality permit as well. However, that permit will be considered separately from the water quality certification which is required as DNR and the Corps decide on whether to grant Formosa a permit to build on designated wetlands.

Race, however, is a factor in the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ deliberative process.

Ricky Boyett, public affairs chief for the Army Corps’ New Orleans office, explained in an email: “The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ obligation is to address, within the scope of our statutory authority, whether our permit decision will have a disproportionate impact on minority and/or low-income populations. Every permit decision includes an environmental justice analysis that evaluates whether or not the proposed action will have a disproportionate effect on these communities.”

But even if racial discrimination factors into this project, racial injustice is unlikely to stop it. According to a report by the Center for Public Integrity, researchers with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency under Obama concluded that African Americans are subjected to higher levels of air pollution than white Americans, regardless of their wealth. Even so, Title VI complaints alleging environmental injustice generally end with no formal action on behalf of communities of color.

Formosa’s Record of Spills, Violations, and Lawsuits

Members of VAYLA, a community group representing African Americans and Vietnamese Americans battling against a proposed natural gas plant in New Orleans East, spoke in opposition to the Formosa plant. They brought up the company’s blemished record, including a Formosa steel mill’s toxic spill that killed tons of fish in Vietnam in 2016.

Mark Nguyen, with VAYLA, asked the government officials to “look at the quality of life over the dollars signs and vote with the people to oppose this plant.”

Formosa has also been cited for environmental violations at locations in Louisiana and Texas and faces a lawsuit in Texas for plastic pollution on Gulf Coast beaches.

The company’s record is so bad that German environmental organization Ethecon Foundation awarded Formosa “The Black Planet Award,” which it gives to companies deemed to be destroying the planet.

‘Poisoning my people is not civil’

Pat Bryant, a New Orleans human rights activist, warned that people would rise up against the government for granting permits allowing more pollution, and that there would be a protest march from New Orleans to Baton Rouge in April 2019.

Pat Bryant speaking against Formosa’s proposed plastics plant in St. James Parish.

When the hearing officer cut off Foytlin, Bryant rose in her defense and spoke even after being told what he was saying was off the record. “What is going on here is very profane. What you are doing is against humanity,” he said, adding that if Jesus were present, he would say, “Fuck you.”

Klie Kliebert, a New Orleans resident with family roots in St. James Parish, spoke after Foytlin and also defended her. “You want my people to be civil but this is not civil — poisoning my people is not civil,” Kliebert said. “I’m opposed to racism, which means I’m opposed to this plant.”

Permit officer Smith gave Foytlin another chance to speak on the record at the end of the hearing, pointing out that she could say what she wanted as long as she didn’t use expletives.

“You worry about our words while you poison our people,” Foytlin responded, before calling Smith a racist and storming out of the meeting.

Update 12/13/18: An earlier version of this story misspelled Meg Logue’s surname. We regret the error.

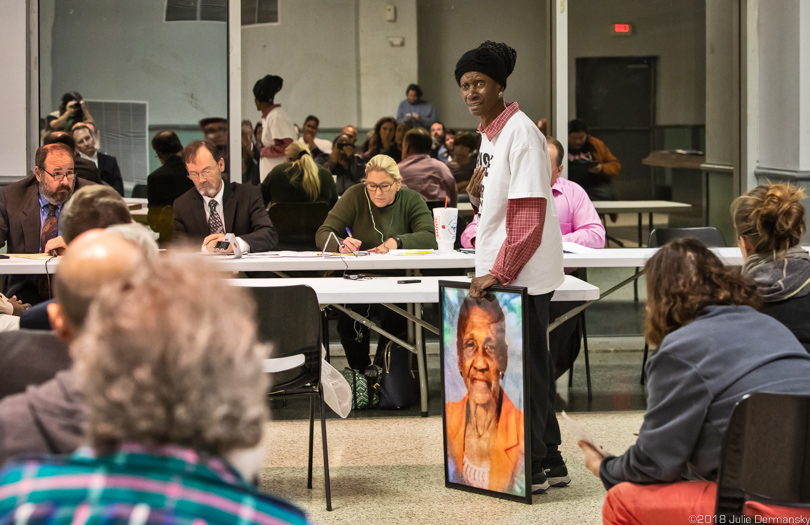

Main image: Rita Copper, a resident of St. James Parish, holding a photo of a deceased friend who died of cancer. “We are already plagued with plants. They are killing us,” she said while speaking out against Formosa’s plant. Credit: All photos by Julie Dermansky for DeSmog

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts