The U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) reported in September that crude oil exports are continuing to set records, mostly due to the fracking boom in the Permian Basin, in Texas and New Mexico. June exports hit a record 2.2 million barrels per day, while the monthly average was up almost 80 percent for the first half of this year compared to the same period last year.

And crude oil exports are supposed to double by 2020, according to the San Antonio News-Express. That’s a lot of oil — and almost all of it is fracked.

That should come as no surprise. In August 2015, my story for DeSmog, “Lifting Ban On U.S. Crude Oil Export Would Enable Massive Fracking Expansion,” pretty much sums up what is happening now. However, that’s not what the industry experts at the time were predicting.

Last year I noted how quickly these experts, from energy consultants to academics, were proven wrong in their predictions about the effects of overturning the 40-year-old ban, which occurred in December 2015.

If exports double by 2020, those experts will be that much more wrong. Perhaps the best example of this phenomenon is from a December 2015 newsletter from CME Group — a commodities trading group that stood to profit greatly from trading U.S. exported oil. The newsletter, which takes a question-and-answer format, included the following:

Question #2: Will lifting the crude oil export ban result in greater U.S. production?

The answer: No.

Couldn’t get more wrong that, but CME now lists U.S. WTI crude on its website as one of the top commodities it trades. I guess there’s a lesson here about whether to trust a commodities trader.

How About Those Gas Prices?

In a masterful move of public relations aimed at lifting the crude export ban, oil companies (and the many consultants and academic institutions funded by oil companies) argued one of the main reasons to lift the export ban was to help the American consumer.

As I wrote in 2015: “In a recent congressional hearing on the subject, members of congress and those testifying repeatedly stressed the point that lifting the ban is ‘about the consumer.’”

The claim was that exporting U.S. crude oil would actually lower U.S. gas prices. While counterintuitive, the argument went that more oil on the global markets would lower global oil prices, which in turn would lower U.S. gas prices

How’s that working out?

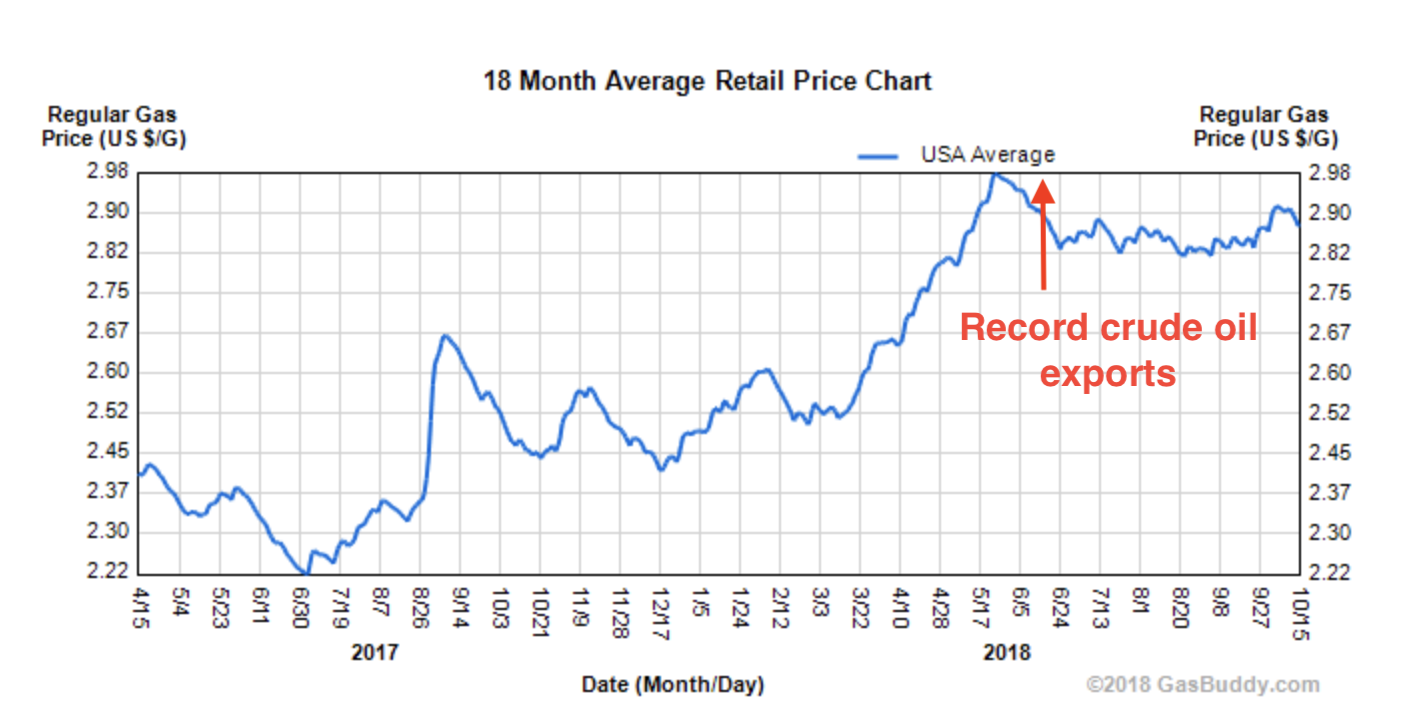

In May 2018, U.S. gas prices reached the highest levels in years, followed by record crude oil exports in June.

While many factors influence the price of oil, the argument that exporting oil would lower U.S. gas prices appears deeply flawed. Most likely, it was nothing more than a public relations effort that helped members of Congress justify their votes to lift the ban.

Sorry, American consumers.

China, Oil, and National Security

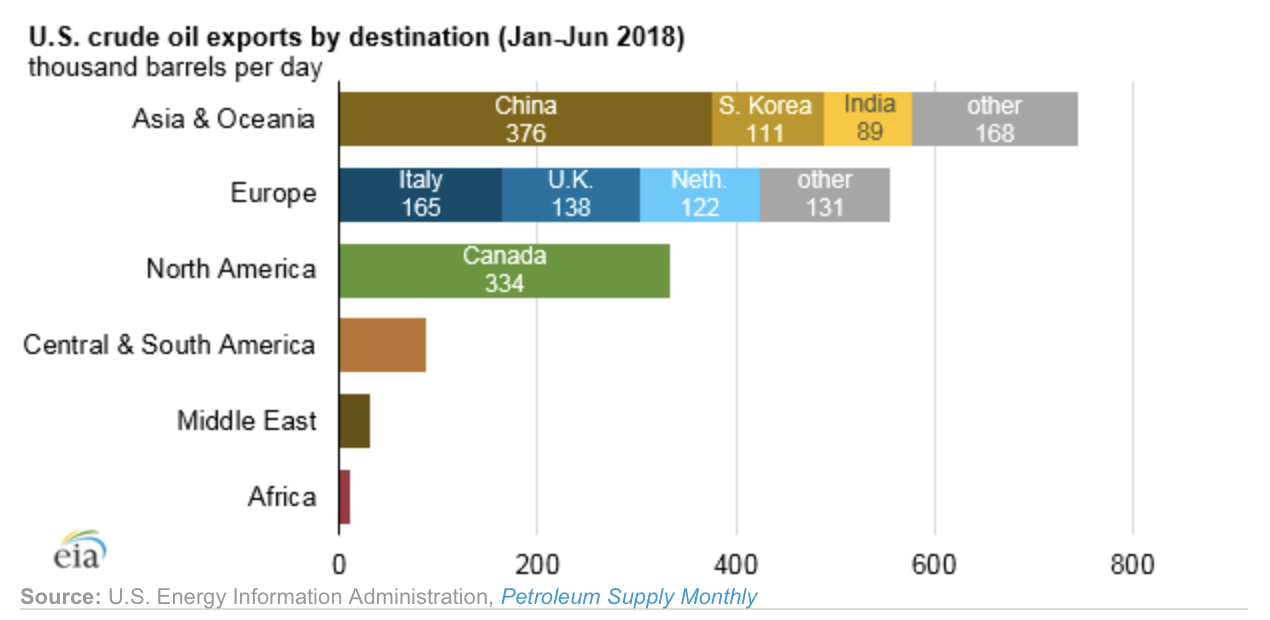

With U.S.-China relations growing increasingly antagonistic — “cold war” appeared in headlines on CNN, The Wall Street Journal, and Financial Times in the past week — it’s also a good time to revisit another argument for exporting U.S. crude oil: national security. This is a claim I’ve debunked repeatedly.

And yet which country has been the top destination for U.S. crude oil? China.

Of course, where the oil goes is determined by commodities traders like CME, not by the U.S. government and its priorities.

This might be a good time to revisit Harold Hamm’s response when asked by Congress, under oath, if he thought U.S. crude oil would be exported to China should the ban be overturned. Hamm is the CEO of Continental Resources, one of the larger companies producing oil by fracking, and was one of the biggest proponents of lifting the crude export ban.

Hamm’s response? “I don’t see a lot of that trade happening.”

Wrong again.

And apparently Hamm changed his mind because Continental has been selling oil to China.

Exporting Climate Disaster, Creating Environmental Disaster at Home

With climate scientists’ recent (and increasingly dire) warnings about the need to stop burning fossil fuels, the prospect of U.S. oil exports doubling by 2020 is concerning. But the effects of this rise in oil production are local too.

“Blowout,” a recent in-depth collaboration among news organizations, chronicles the impacts and implications of the fracking boom in West Texas that coincides exactly with the current export boom:

“Booms, predictably, bring air pollution, oil spills, groundwater loss, and contamination. But the state isn’t tracking or policing these problems aggressively.”

A particularly troubling local impact of all that fracking is the sheer amount of water it uses and then the resulting toxic wastewater it struggles to dispose of.

At a time when bold initiatives are needed to drastically reduce the world’s dependence on fossil fuels, the fracking boom in Texas and New Mexico and subsequent export boom is a shining example — illuminated by the flares of fracked gas — of exactly what not to be doing.

Main Image: Oil tanker in Houston ship channel. Credit: Roy Luck, CC BY 2.0

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts