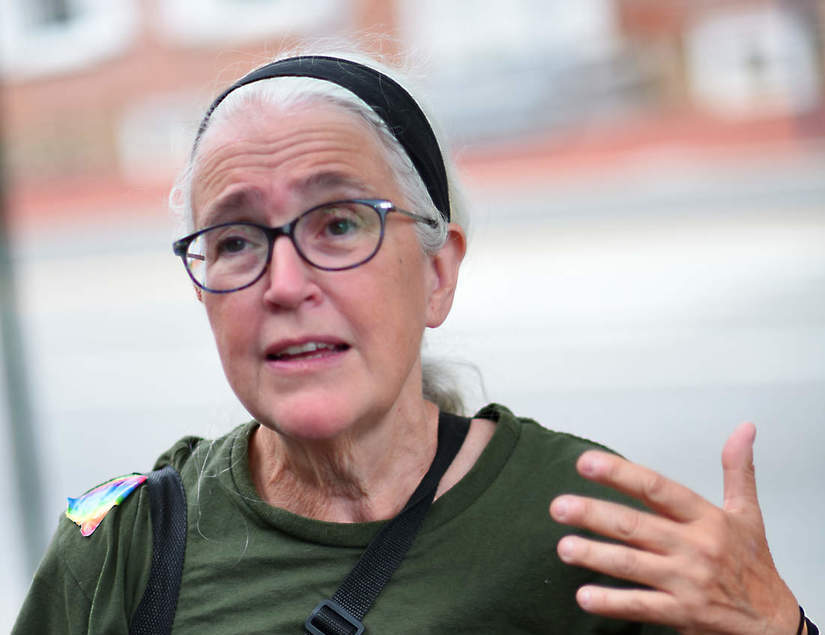

On Tuesday, July 26, Sunoco Pipeline L.P. filed paperwork with a Pennsylvania court claiming that retired special education teacher Ellen Gerhart, 63, had violated an injunction. Three days later, Gerhart was arrested and jailed.

After being held on $25,000 bail for a week, Ellen Gerhart was on Friday, August 3 sentenced to two to six months by Pennsylvania Court of Common Pleas Judge George Zanic.*

Sunoco Pipeline obtained a right of way through the Gerharts’ land using the controversial legal doctrine of eminent domain, which allows private companies to seize land people refuse to sell that’s in the planned path of a pipeline project.

In the complaint that led to her jailing, Sunoco claimed Gerhart interfered with construction by, among other things, luring mountain lions and bears onto her property.

“Mrs. Gerhart’s efforts to bait the property was [sic] successful and, on June, 24, 2018, a mountain lion was spotted on the edge of the easement,” the complaint filed by Sunoco Pipeline, L.P., which merged with Dakota Access builder Energy Transfer Partners in 2017, alleges. “Four days later, two bears were on the easement and fresh mountain lion tracks discovered.”

These allegations have drawn ridicule from Gerhart’s supporters, who say the company’s claims that she is to blame for wildlife near construction are absurd. A MoveOn petition calling the charges “outlandish and unprovable” and urging her release has attracted over 2,000 signatures.

The Gerharts have their own view of what led to Ellen’s arrest.

“Energy Transfer Partners is yet again fabricating charges against my mom in attempt to silence her,” Ellen’s daughter Elise said in a statement. “Look at who has actually inflicted damage here: ETP has poisoned dozens of families’ wells across the state, spilled over 100 times, and harassed and intimidated anyone who opposes them.”

Bear Habitat

Indirect criminal contempt, the charge listed against Gerhart, generally carries a maximum penalty of 15 days imprisonment and a $100 fine. By the time Sunoco’s claims against Gerhart were heard on Friday, she had served roughly seven days, much of that period in solitary confinement, according to her supporters.

A court docket listed the charge against Gerhart as a summary offense, a type of criminal charge that most often results in the issuance of a ticket and no jail time. She was facing two other charges, her lawyer said, but those were sheduled for trial at a different hearing.

The state’s game commission reports the last recorded killing of a mountain lion in Pennsylvania dates back to the late 1800s. Mountain lions are considered extinct east of the Mississippi River and north of Florida (though other large cats like the endangered Florida Panther have at times ranged far from their homes or escaped captivity).

Gerhart’s daughter Elise dismissed Sunoco’s claims as entirely unfounded.

For her, the explanation of what happened was simple. “We live in bear habitat,” she said. “There are bears.”

What Rights Remain After Eminent Domain?

The charge listed against Gerhart was a low-level contempt charge, but her case could also implicate much larger questions about property rights and eminent domain, questions that boil down to this: What can you do on your own land after a private company seizes a slice using eminent domain?

If Sunoco’s charges are upheld, that could potentially set precedents affecting others who live near pipeline projects, especially those who wind up in disputes with a company over the use of their land. What if, for example, a landowner keeps a compost pile for their garden near land seized for a pipeline — could that person wind up accused of using their kitchen scraps to attract dangerous wildlife? The two activities might look pretty similar from a distance.

What if you have a campfire out back — is that criminal conduct intended to menace with fire or just a normal, everyday activity?

Can a private company seek to have you jailed if you shout at construction workers — or should that run afoul of the First Amendment’s protections for free speech?

And what happens when a company brings in security guards to keep trespassers out, but those guards wind up routinely photographing you walking around your own land and keeping detailed daily logs of your activities — should their eminent domain rights to use your land extend that far? Or should the daily photographing of a person on their own property cross a line into an invasion of privacy, what the courts in Pennsylvania might call an “intrusion upon seclusion”?

These are the sorts of thorny legal questions that are only beginning to emerge amid two separate developments, which highlight the problems that arrive when a doctrine originally intended to promote public works projects and utilities is increasingly applied in ways that benefit large corporations, who use land very differently than, say, a town building a public park or a phone company installing a telephone pole — and who are more likely to be confronted by landowners outraged by the seizure of their land for someone else’s profit.

The first development happened in 2005, when the Supreme Court’s decision in Kelo v. City of New London broadened the government’s authority to condemn land through eminent domain for purposes like economic development — meaning that private companies are increasingly able to have people’s land condemned.

The second development, the explosion of shale gas drilling, has brought pipeline companies into more and more backyards, farms, and neighborhoods nationwide. This rush of construction is making questions about which pipelines should be considered “public utilities” — or which companies may have the right to seize private lands — all the more pressing.

The pipeline industry plans to construct over 3,200 miles of oil and gas pipelines this year, more than double the number of miles built in 2017.

Legal challenges to the “public utility” status of Mariner East projects, which will carry natural gas liquids like propane, ethane, and butane for export and use in the petrochemical and plastics industry, have repeatedly failed in Pennsylvania.

While the courts may be convinced that Mariner East is a public utility, some public interest groups remain very skeptical, arguing that it violates common sense to classify exports of a petrochemical ingredient as a “utility.” In other words, your utility bills might include a power bill, a water bill, or a phone bill — and the power company, water company, and phone company all have a right to run their pipes and lines across your land, even if you object — but who pays a monthly ethane bill?

And if people aren’t convinced that land seizure is justified, they’re more likely to push back. “The growing use of eminent domain to seize property for pipelines has generated opposition from an unusual coalition of liberal environmentalists and conservative and libertarian property rights advocates,” a 2016 Washington Post column noted.

‘Prioritization of Profit’

Back in 2015, Sunoco approached the Gerharts with an offer to buy a portion of their land — an offer that the Gerharts refused. The company responded by seizing that land through eminent domain.

In January, the state Supreme Court rejected an appeal of a 2017 ruling granting Sunoco 1.4 acres out of the Gerhart’s 27 acres of land.

However, environmental and safety concerns, rather than property rights, have fueled much of the opposition to Sunoco’s Mariner East plans.

“We started really doing some research on this company and on the product it was carrying,” Ellen Gerhart told PBS Newshour, which profiled the family and their supporters last year. “The more research you do, the worse the picture gets.”

Pipeline opponents had at one point set up a protest encampment on the Gerharts’ land, using civil disobedience tactics to stall construction — until in April, a “predawn timbering raid” by Sunoco, which had hired controversial private security firm TigerSwan, felled the trees while they were unoccupied. (There is no mention of any protesters remaining present at the Gerhart property in Sunoco’s complaint filed last week.)

For Sunoco’s part, Mariner East’s track record during construction statewide has proved troubling, involving not just accidents but also what one state judge called “deliberate managerial decisions.”

“Sunoco has made deliberate managerial decisions to proceed in what appears to be a rushed manner,” the administrative law judge wrote in a May 21 shutdown order, “in an apparent prioritization of profit over the best engineering practices available in our time that might best ensure public safety.”

“The pipeline project has been plagued by spills and mishaps, racking up over 100 spills and creating huge sinkholes in suburban subdevelopments,” DeSmog previously reported. “In addition, it has been blamed for the contamination of a dozen water wells and hit with fines as high as $12.6 million by state regulators over permit violations.”

In February, the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection took the rare step of labeling some of Sunoco’s environmental lawbreaking “willful and egregious,” and construction has been repeatedly suspended by the state and then resumed.

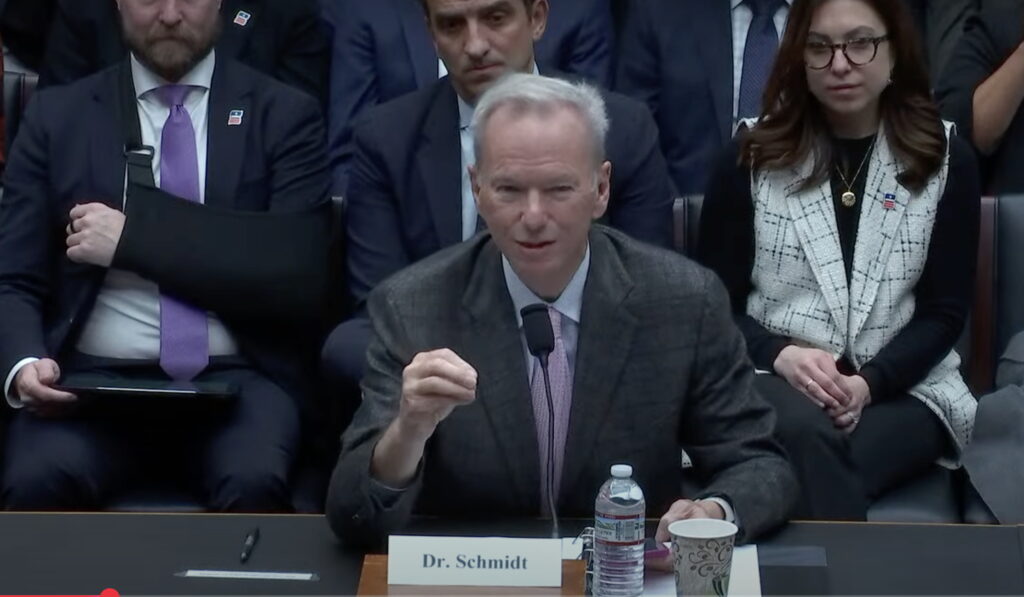

Judge Zanic, who sentenced Gerhart on Friday, worked as a District Attorney (or prosecutor) before being elected to the bench in November 2013. His current term runs for another five years, to 2023. He made headlines two years ago for holding pipeline protesters on bails up to $200,000.

A GoFundMe page to help with legal expenses from today’s trial had raised roughly $8,000 of a $25,000 goal as of Friday afternoon.

*UPDATED: This article has been updated to reflect developments on Friday, August 3.

Main image: Ellen Gerhart. Credit: © Laura Evangelisto 2018

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts