By Dave Levitan. Crossposted from Climate Liability News.

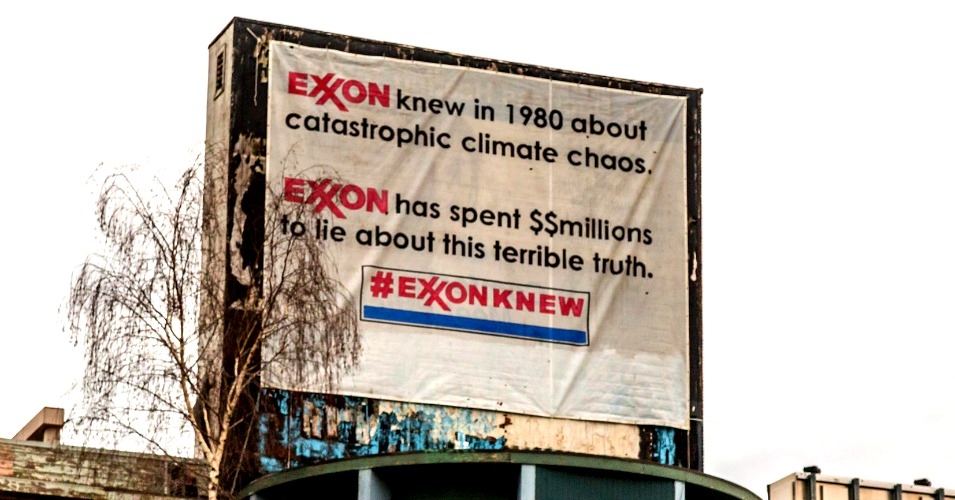

A peer-reviewed analysis of 37 years of communications from ExxonMobil concluded that the oil company has misled the public for decades about climate science and climate change. When their communications were aimed at the public and non-scientific audiences, they focused on doubt and uncertainty. At the same time, the company’s internal communications and peer-reviewed science broadly agreed with the scientific consensus that fossil fuel burning is warming the planet.

“Available documents show a systematic discrepancy between what ExxonMobil’s scientists and executives discussed about climate change privately and in academic circles and what it presented to the general public,” the study concluded. It was researched and written by Harvard professor Naomi Oreskes and Geoffrey Supran, a postdoctoral fellow in Harvard’s Department of the History of Science.

Oreskes has long studied the history of scientific consensus and dissent around climate science and wrote the book Merchants of Doubt to shed light on the deception of a small group of scientists to further a political agenda around climate change and other environmental issues.

She and Supran undertook an analysis of Exxon’s communications as the attorneys general of two states have been investigating whether the company violated various consumer or investor protection laws by misleading the public. Exxon has pushed back against revelations initially made by InsideClimate News as well as by the Los Angeles Times and Columbia University’s Graduate School of Journalism that the company has been studying climate science for decades while simultaneously promoting doubt about the scientific consensus to help block climate action.

Exxon claims it has long been transparent about climate science and associated risks. On a website devoted to this issue, the company notes that it “has continuously, publicly and openly researched and discussed the risks of climate change, carbon life cycle analysis and emissions reductions.”

But those claims are directly challenged by the new report.

“Supran and Oreskes’ paper demonstrates quantitatively what we’ve known qualitatively for years now: despite its own clear knowledge of climate science and climate risks, Exxon ran an active, well-funded communications campaign to dismiss those risks for decades,” said Carroll Muffett, an attorney and the president and chief executive of the nonprofit Center for International Environmental Law.

Following the media investigations, Exxon argued that the reporters cherry-picked documents out of a large cache of research. “So we decided to look at the whole tree,” Oreskes said in a telephone interview.

The new analysis, published on Wednesday in the journal Environmental Research Letters, makes no claims regarding the legality of Exxon’s actions, and focuses instead on whether or not the company’s internal and external communications suggest a pattern of deception.

“There’s no question” regarding this discrepancy, Oreskes said.

Supran and Oreskes studied and compared 187 individual communications between 1977 and 2014, including peer-reviewed and non-peer-reviewed publications, internal company documents, and “advertorials” — paid advertisements addressed to the public and published in the New York Times.

They examined each document’s position on climate change as real, human-caused, serious, and solvable, as well as on acknowledgement of the risk of assets being stranded or unusable as the climate continues to warm. The authors found that in general, as documents became more public, they increasingly focused on or highlighted doubt and uncertainty in climate science.

Of all the peer-reviewed scientific papers that Supran and Oreskes reviewed, about two-thirds expressed a position, one way or the other, on anthropogenic global warming. Of those, 83 percent acknowledged that it is real and human-caused. Most non-peer-reviewed and internal documents also take this stance, though there are some with more of an “acknowledge and doubt” position.

Meanwhile, 81 percent of the advertorials written by Exxon took a “doubt” position on the reality of climate change and only 12 percent acknowledged the science. The difference between the advertorials’ positions and the other documents was statistically significant, the authors said.

Analysis of every document is provided in hundreds of pages of supplemental information, but the paper itself highlights a number of illustrative quotations. For example, a 1996 peer-reviewed paper stated that “The body of statistical evidence … now points towards a discernible human influence on global climate.”

That same year, an Exxon advertorial seemed to undercut that conclusion: “Global warming: who’s right? Facts about a debate that’s turned up more questions than answers.” It went on to call the “theory” that fossil fuel burning can affect the Earth’s climate “unproven.”

“In public, ExxonMobil contributed quietly to the science and loudly to raising doubts about it,” Supran and Oreskes wrote. They also pointed out several instances of clear factual misrepresentations in the advertorials, including the idea that the warming effect of greenhouse gases is offset by a cooling effect from other particulate products of combustion of fossil fuels. Exxon scientists had reported being “not very convinced” of this theory a decade earlier and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change had rejected the concept a year before that advertorial was published.

Exxon seems to have approached the concept of stranded assets differently in different types of communications as well. The idea is mentioned in 24 peer-reviewed, non-peer-reviewed, and internal documents, but never in an advertorial.

The discrepancy between the advertorial content and that of the other types of documents is important, the authors suggest, because of the difference in these communications’ reach. Peer-reviewed and non-peer-reviewed publications are difficult for the public to access (to say nothing of the internal documents), and likely each one had a readership of only “tens to hundreds,” according to Supran and Oreskes. Meanwhile, Exxon paid for an advertorial in The New York Times every Thursday between 1972 and 2001; the company was responsible for one-quarter of all advertorials printed on the Times’ Op-Ed page over that span. These had a readership numbering in the millions.

The authors note the limitation inherent to a textual analysis like this one, in that judgments must be made on the meaning of each of the documents. Still, they argue this should not undercut the findings. “We feel confident that the discrepancies that we found are sufficiently great that anyone else doing this … would get essentially the same result,” Oreskes said.

Experts say this may be an important input to the ongoing legal battles surrounding this issue. “Most significantly from a litigation perspective, Exxon targeted its misinformation at the media most likely to reach and inform millions of consumers and investors, leaving its acknowledgment of climate realities to specialty publications,” Muffett said. “Exxon argues that publishing climate science gives it some plausible deniability in its denial campaigns. It’s increasingly unlikely a jury would agree.”

Danielle Fugere, president of the nonprofit As You Sow, which works to promote corporate social responsibility, said Exxon’s true colors show through in the report.

“This analysis, while not surprising, highlights a deeply troubling disregard for the public good,” Fugere said. “We have seen this story play out before — from asbestos, to lead, to cigarettes, naming just a few — plausible deniability in the face of clear science has been used time and again by companies and industries to delay protective action. What is constantly surprising is that government leaders and agencies fall for it every time.”

Image credit: CommonDreams.org

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts