Hydraulic fracturing (“fracking”) and offshore drilling garner a lot of news headlines when it comes to oil and gas issues in America, but they’re far from the only game in town, with those two drilling techniques not even constituting the majority of U.S. oil and gas production.

For that, look to enhanced oil recovery (EOR), an under-regulated drilling method that has been around for over a century and could be threatening drinking water sources — if only regulators and the public had enough information to determine that danger, according to a new 63 page report published this week. Environmental group Clean Water Action, with graduate students from Johns Hopkins University, plumbed the academic and professional literature on EOR and its associated regulatory issues in order to lay out the potential environmental and public health risks posed by EOR. They also detail how the drilling method came to be handled with such a light touch by regulators at both the state and federal level.

The report details that the almost non-existent regulatory treatment for EOR, which makes up 60 percent of U.S. oil and gas production, may be further watered down due to proposed U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) budget cuts by the Trump administration. In addition, oil, gas, and coal companies are pushing for two Senate bills offering tax incentives for this drilling technique which cast it as a supposed climate change solution.

Meet Enhanced Oil Recovery

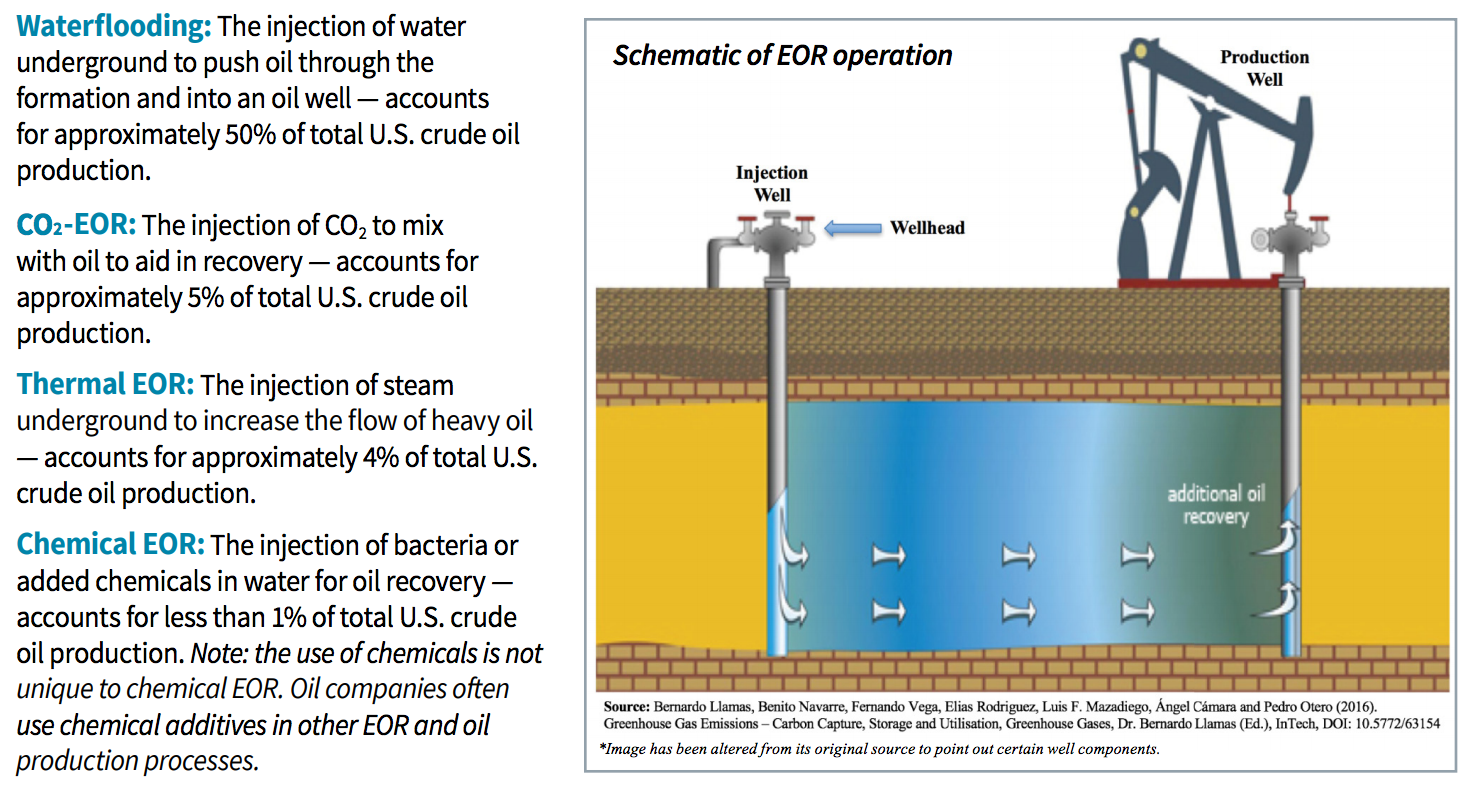

Boiled down, EOR is a drilling process that taps into an already drilled oil well, in order to get even more out of what the report calls the “original oil in place,” or OOIP. When most wells are drilled initially, industry only captures about 10 percent of the oil from the ground. Thus, EOR procedures are used to recover more — though not all — of the remaining product.

The report, titled “The Environmental Risks and Oversight of Enhanced Oil Recovery in the United States,” details the four main types of EOR: Waterflooding, CO2–EOR, Thermal EOR, and Chemical EOR. Carbon dioxide EOR will come up again later.

Credit: Clean Water Action

The method known as “waterflooding” has the ability to recover an additional 20-40 percent of the oil in the ground, the report highlights, while the other EOR technologies help boost that amount to 30–60 percent of the initial oil coming from beneath the surface.

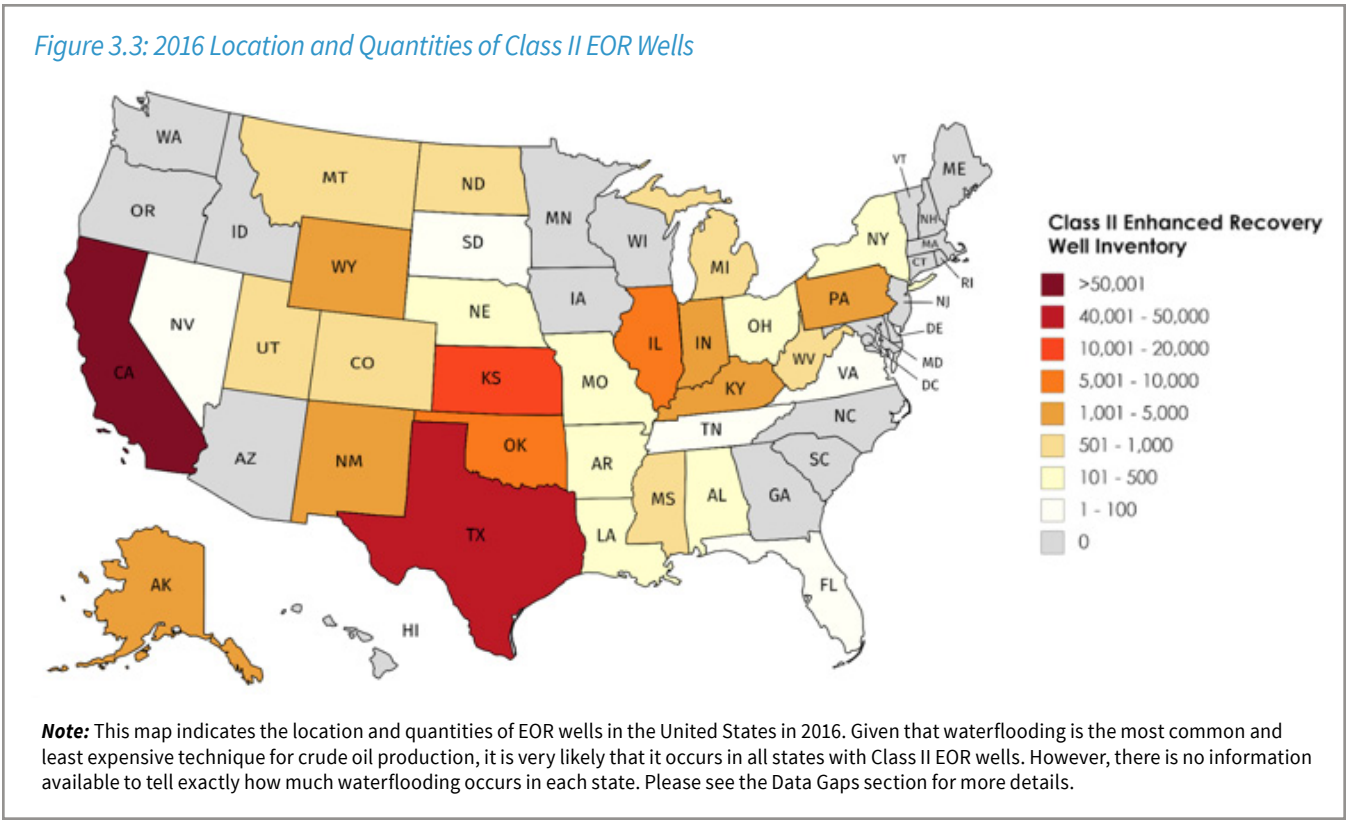

While California is often pegged as leader of the resistance to President Donald Trump‘s anti-environmental agenda, the report highlights just how much the Golden State is also a Fossil Fuel State: it has over 54,000 EOR wells. Other states not typically considered oil and gas producing powerhouses but also lead the way in EOR production include Kansas, Illinois, New Mexico, and Kentucky. Those four states have a combined 24,993 EOR wells, or about one-sixth of the country’s total.

Credit: Clean Water Action

Regulatory Issues

As the report explains, the EPA classifies EOR under the Safe Drinking Water Act as a Class II underground injection well, the same category as the underground injection of the brine or waste products coming from oil and gas drilling processes.

The regulations for EOR were created in the 1980s and have not been updated since. Further, regulations for EOR and waste injection wells occur mostly at the state level, something the report says the oil and gas industry successfully lobbied to achieve.

Both states and the EPA, though, lack the regulatory funding and inspectors for meaningful oversight of what amounts to over 145,000 of these wells nationwide.

California, for example, has 54,102 EOR wells but only 52 state staffers working on underground injection control issues, translating to one employee for every 1,040 EOR wells. Texas has it even worse, with 15 state administrative staff and 180 EOR well inspectors for 40,421 statewide EOR wells. That’s one staffer for every 2,694 wells or one inspector for every 224 wells.

Beyond lack of staffing and oversight, there’s also very little data gathered about EOR operations which are available to the public.

“Data collection and management at the state level is neither satisfactory nor uniform, inhibiting proper oversight,” the report explains. “Additionally, states prepare little information about EOR for a public audience, and state regulatory websites vary in both content and quality. State regulatory agencies are often not equipped with sufficient staffing or budgetary resources to cope with daily responsibilities that have been increasing since [the Safe Drinking Water Act Underground Injection Control program’s] inception.”

Water Safety Concerns

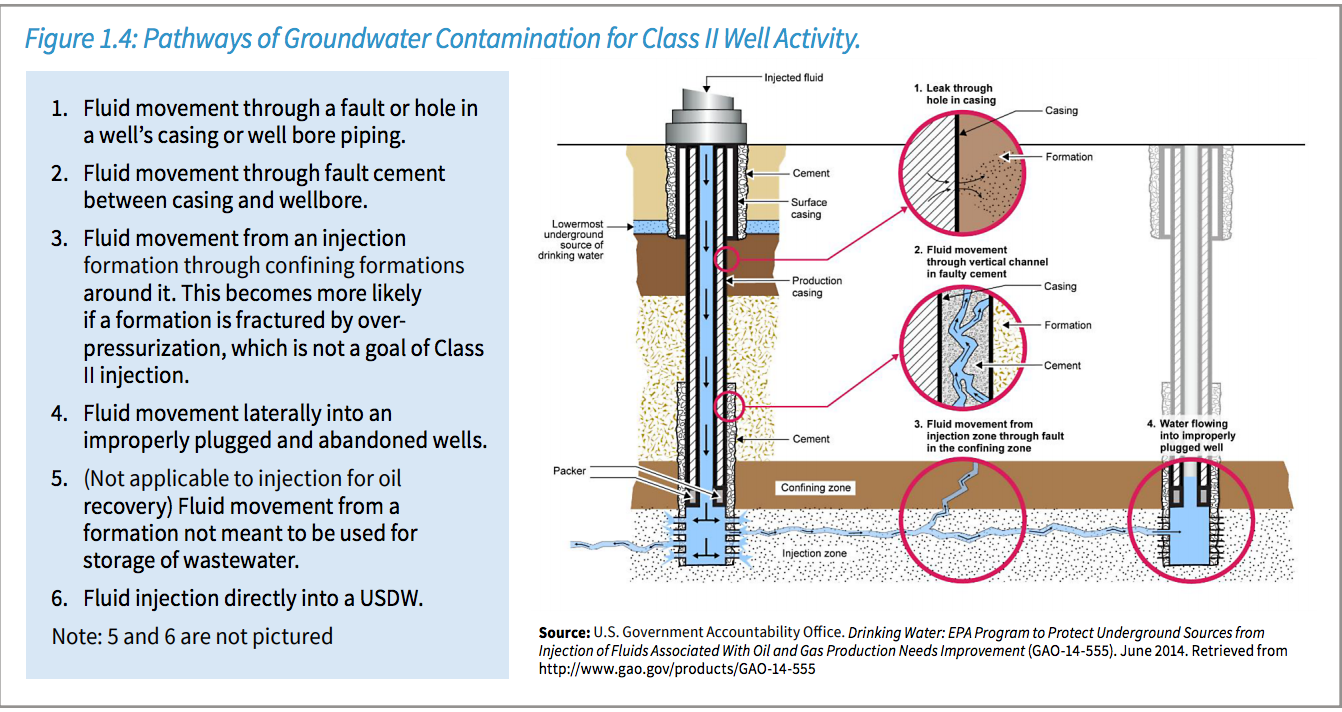

Most concerning, perhaps, is the lack of transparency surrounding the chemicals injected underground during the EOR process. These chemicals, whose contents are not required to be disclosed under federal law, have numerous potential pathways to contaminate groundwater.

“In general, contamination pathways are closely related to possible issues with well cement, casing, and piping. In addition to pathways created by inadequate well construction, waterflooding and EOR activities have some risk of corrosion of well materials that can create additional pathways for leakage,” reads the report. “As a result, proper well construction (including materials used) is the single most important element to the effective protection of [Underground Sources of Drinking Water] after well siting.”

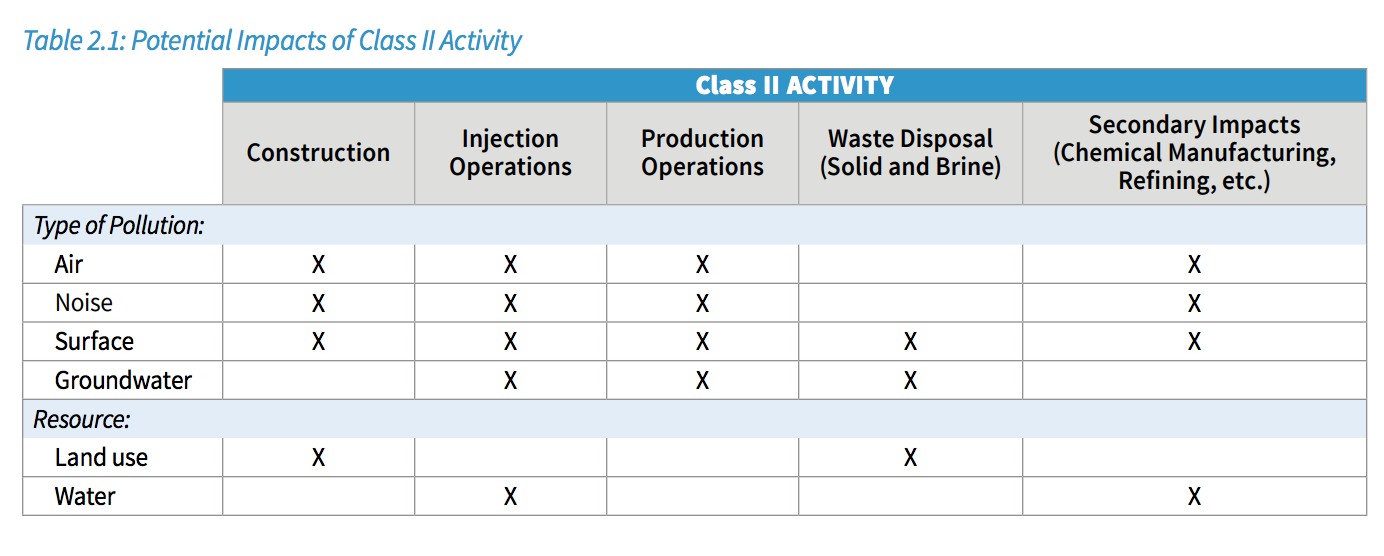

Beyond potential water impacts, other environmental effects include air pollution, noise, surface, and other land use issues. The best known surface issue, for example, has been earthquakes resulting from the injection of fracking waste into underground wells, particularly in the state of Oklahoma.

“It is worth highlighting that only injection operations are regulated by the [EPA‘s Underground Injection Control UIC] program — even air and noise pollution caused by injection are not regulated under UIC. However, the noted potential effects of Class II activity remain regardless of which regulatory program oversees them,” the report notes.

Credit: Clean Water Action

Lobbying for Enhanced Oil Recovery

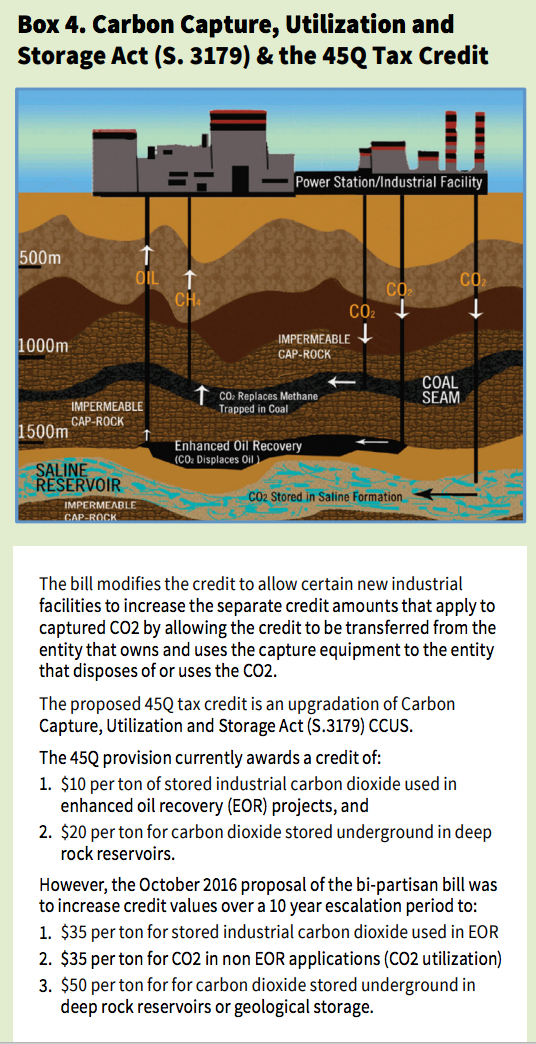

While EOR appears to be off the radar for most people, the oil, gas, and coal industries have shown clear interest in the technique, and have actively lobbied for two bills which would offer higher tax incentives for a form of EOR called carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS).

Those bills, the Carbon Capture, Utilization and Storage Act (S. 3179) and the Carbon Capture Improvement Act (S.843), will offer increased tax credits under the federal government’s 45Q program, a section of the U.S. federal tax code which incentivizes the capture and storage of carbon dioxide in underground geological formations.

The legislation is being sold as a climate change solution, despite both a lack of scientific evidence supporting that claim and its primary lobbying proponents being fossil fuel corporations, such as ExxonMobil, Peabody Energy, Arch Coal, and Cloud Peak Energy.

Credit: Clean Water Action

“Because some CO2 — a greenhouse gas — is trapped underground when it is used for EOR, pairing [carbon dioxide injection] EOR with CCUS is often touted as a technique for curbing climate change — and thus as a net environmental benefit. However, the evidence of this net benefit is speculative and highly disputed,” reads the report. “Given the enormous variability in subsurface conditions, the extent the CO2 actually stays in the desired formation without any migration is unclear.”

For example, one 2015 report published by the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives concludes that for every ton of CO2 injected during the CCUS process, 2.7 tons are emitted eventually, because, of course, this process is retrieving oil that will end up burned and releasing additional CO2 into the atmosphere.

These are just a few of the concerns outlined in the Clean Water Action report.

Trump Budget Cuts

The EPA, now run by the climate change denier Scott Pruitt under the Trump administration, has yet to provide a detailed report on the environmental costs and consequences of EOR since a 1981 report. Even that report came to conclude that many of the potential hazards are unknown and require much more detailed study. However, this early examination of the predominant oil and gas drilling production method in the U.S. has received no meaningful follow-up for over three decades.

Despite a fairly laissez faire approach to EOR so far, in theory, the EPA has multiple options at its disposal. That includes performing or funding more research on EOR, auditing state regulatory programs for this drilling process, and even getting rid of state oversight if non-compliance with state regulations becomes an issue. In practice, the EPA has chosen to sit on its hands and was criticized for doing so in a 2014 Government Accountability Organization report. This trend is almost guaranteed to continue under the budget cuts for the underground injection control program (UIC) proposed by the Trump administration.

“The budget proposed by the Trump administration calls for a cut in UIC Program funding by $3,166,000 down to $7,340,000,” the report details. “This development is alarming, because it sets a precedent against preventive regulation of the oil and gas industry. If state regulatory agencies are ill-equipped to carry out their daily routine activities, they cannot prevent contamination effectively.”

The report ends with a call to regulatory and oversight action for EOR for both the EPA and the states, but today’s political climate makes that ambition seem unlikely at best.

Credit: Clean Water Action

Main image: Hundreds of Chevron oil pump jacks in the Lost Hills Oil Field in the San Joaquin Valley in Central California. Credit: Richard Masoner, CC BY–SA 2.0

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts