The North Sea oil and gas industry is the gift that keeps on giving when it comes to emitting dangerous greenhouse gases.

Shell and Exxon are packing up and moving out of the famous Brent oil and gas field in the North Sea. As a final hurrah, almost 800,000 tonnes of carbon dioxide will be emitted as four platforms are dismantled and parts are either left to erode in the ocean or moved onshore and recycled.

That’s equal to about five percent of the UK‘s North Sea industry’s annual emissions — from the start to very end, the Brent oil field continues to contribute to climate change.

But emitting hundreds of thousands of tonnes of dangerous greenhouse gases including carbon dioxide, nitrous dioxide and sulfur dioxide into the atmosphere is not the only environmental danger that comes with plugging and abandoning the wells.

Decommissioning

Shell and Exxon own four platforms in the Brent field, famous for its oil barrels that help set an international benchmark price.

Exxon has a roughly even stake in the platforms in the guise of a brand familiar to UK’s drivers, Esso. But it’s Shell that is leading the Brent decommissioning efforts.

The field was discovered in 1971 and started production in 1976. Since then it has produced two billion barrels of oil and six trillion cubic feet of gas, according to Shell. It is located about 136 kilometres east of the Shetland Islands, and about 480 kilometers north of Aberdeen.

In a 322-page document submitted to the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) last week, Shell outlined how it intends to end the life of the field now that “all the economically recoverable reserves of oil and gas have been extracted”.

The documents are now open for consultation, and the public has until April 10 to comment on the plans.

Shell said it came to the decision to decommission its wells on the basis that “reuse was not a credible option because of the age of the infrastructure, its distance from shore, the lack of demand for reuse and the cost of converting the facilities”.

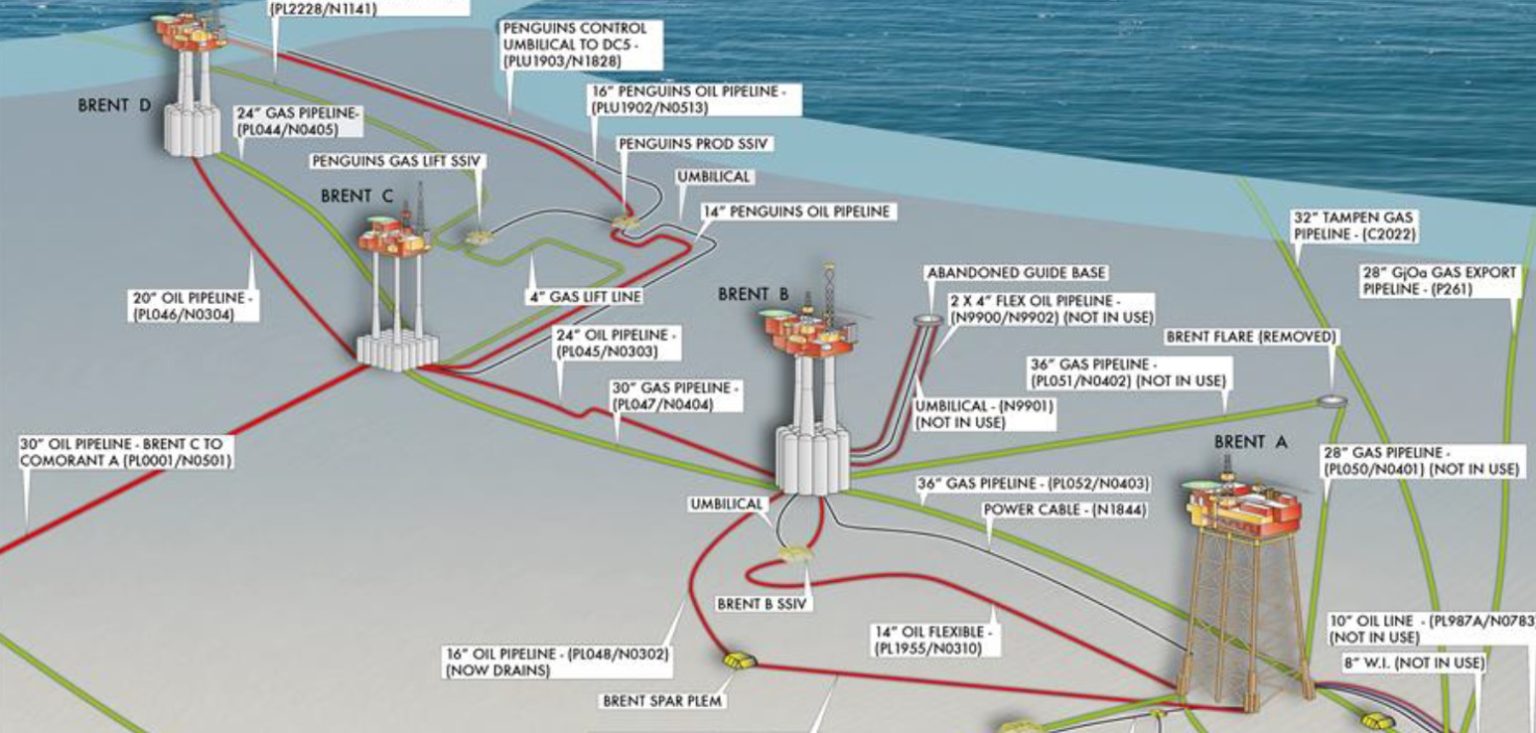

The Brent field is served by 103 kilometers of pipeline, and Shell will need to decommission 295,000 tonnes of steel, 568,000 tonnes of concrete, 238,000 tonnes of sand ballast, and 16,000 tonnes of rock-dump, according to the documents. So decommissioning is a major job.

There are lots of stages to the process, which involves:

- Plugging the wells

- Removing the top of the platforms

- Capping the legs, and leaving them in place

- Shifting some of the debris from the drill-holes, while leaving most undisturbed

- Removing sub-sea pipelines

- Marking and monitoring the remains of the field (in a ‘left’ survey, and subsequent survey five years later)

Decommissioning is already underway, Shell said, and should be completed by 2026.

Shell said it came up with the plan after a decade of studies and reviews, each of which tested the economic and technical feasibility of each option.

It was also required to do an environmental impact assessment for each stage, including calculating the energy and emissions involved in decommissioning the equipment.

It tested its decommissioning options against six criteria, giving a different weighting to each one in various scenarios. So the climate impact of leaving the oil field was one of many factors Shell was required to consider when drawing up the plans.

Unsurprisingly, there are some fairly major potential impacts of decommissioning the wells — from oil seeping into the ocean as the platforms are dismantled, to disturbing local communities as parts are brought on-shore for recycling.

That’s on top of the small matter of the 800,000 tonnes of carbon dioxide that will be emitted as various machines burn fuel to plug the wells, recycling facilities power up to reuse material, and ships and lorries carry equipment from the wells to shore.

The equivalent of five percent of the industry’s annual emissions may not seem much when it’s spread over 10 years, and it’s barely a scratch on the amount of carbon dioxide emitted from burning the oil and gas the wells produced over the last few decades. But it does show that the industry continues to be responsible for significant greenhouse gas emissions, and is a major environmental threat, even once the oil and gas fields are spent.

Environmental Concerns

The environmental risks are different for each stage of the decommissioning process.

Shell categorised the emissions associated with plugging and abandoning its wells as a “large negative” of the process. It expects around 24,000 tonnes of carbon dioxide to be emitted as machines pump the remaining oil out of the well hole and fit a new permanent plug.

Leaving the steel and concrete base structures on the seabed could also have environmental ramifications, as they gradually erode over time. This collapse could potentially change the makeup of the seafloor for up to 100 metres around the bases.

Shell admitted the erosion is likely to cause disturbance to lots of “common” species, but said there should be no harm to “species of conservation concern”. Removing seabed equipment will also inevitably disturb marine life that lives on the seafloor, Shell acknowledged.

There are also emissions implications of leaving the legs on the floor — Shell estimated that around 370,000 tonnes of carbon dioxide may be emitted making legs for new projects elsewhere, as the old legs will not be recycled. But it estimated that reusing the legs would lead to about 30 times the emissions of leaving them in place, due to the energy needed to remove and recycle the material.

Perhaps the biggest risk, though unlikely according to Shell, is oil seeping out of the bases. In a ‘worst case scenario’ where a leg falls and breaks and causes structural damage, about 101,900 cubic metres of oily water could seep into the surrounding ocean. The biodegradation of any escaped chemicals would be slow, Shell admitted.

As well as dismantling the platforms, Shell has to decommission the pipelines that serve them. It plans to take 47 kilometers of pipeline back to shore. That could lead to about nine kilometers of new rock dump – new material poured into areas where the pipes previously were.

Shell also acknowledged that there will be some disturbance to local communities as materials from the platforms and pipelines are brought to shore. There will be increased traffic, noise, and dust as various components are transported and cut up on land for recycling.

Once all the materials are removed or secured, Shell will trawl the seabed to check everything is safe, disturbing the top five to 10 centimetres of the seabed and any marine life that inhabits it in the process.

Shell maintained that all its plans are environmentally sound. It claimed to have stress-tested many alternatives, and that the plans would be the same regardless of whether it put the environment or economic concerns first.

WWF Scotland director Lang Banks told DeSmog UK that companies must take responsibility to ensure the long-term safety of the environment they have spent decades disturbing.

“Cleaning up the rubbish left behind by the oil and gas industry is not without risk, but neither is dumping it all on the seabed. Having pushed the boundaries of science and engineering to extract the oil and gas, it’s only right the industry be pressed again to push the same boundaries to remove their potentially hazardous legacy.”

Shell said it is not able to comment on the documents while the public consultation is ongoing.

Just Transition

On the same day that Shell submitted its plans to BEIS, the Scottish government announced a new £5 million fund to upgrade the country’s ports and harbours for decommissioning purposes.

The fund is meant to help local economies benefit from the ever increasing number of fossil fuel companies packing up and leaving the North Sea, with 153 projects due to be decommissioned according to industry body Oil and Gas UK.

The fund shows Scotland is facing up to the realities of the end of the North Sea oil and gas industry, even if the UK government continues to push to maximise revenues from the region.

Ministers appear to be more confident in the industry’s profitability than major corporate players. Both Shell and BP sold off swathes of North Sea assets earlier this year.

The end of the North sea oil and gas industry is an inevitable consequence of ageing oil fields and technological advances and policies that benefit cleaner technologies. But conversations about who is responsible for the economic well being of the communities that rely on the industry are ongoing.

Friends of the Earth Scotland along with six trade unions and WWF Scotland, has released a joint statement calling on the Scottish government to “ take a decisive lead with plans to transform key sectors” so that “no-one left behind in this transition to economic and environmental sustainability”.

The industry should look out for those who serve it, not least as some sort of payback for the environmental damage for which it is responsible, Banks said.

“The impacts of decommissioning are a drop in the ocean compared to the carbon and environmental damage each platform will have caused over their operational lifetime.”

“From start to finish oil and gas extraction does damage to our climate and wider environment. It’s yet another reason why we need to undergo a just transition to a fossil free future”.

Main image and diagrams credit: Shell UK Limited, from decomissioning consultation document.

Oil worker image credit: Tom Haka via Wikimedia Commons CC BY–SA

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts