On February 13 environmental advocates urged Louisiana agencies to deny permits for the Bayou Bridge pipeline at a press conference in front of the Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) office in Baton Rouge.

Five days earlier, a Phillips 66 natural gas pipeline in Paradis, Louisiana, exploded, presumably killing one worker and injuring two. The explosion occurred one night after the Louisiana’s Department of Natural Resources (DNR) held a public permit hearing for the Bayou Bridge oil pipeline at a community center in Napoleonville, Louisiana.

Fire continued raging February 10, the day after an explosion at a Phillips 66 natural gas pipeline in Paradis, Louisiana.

Anne Rolfes of the Louisiana Bucket Brigade talking about the pipeline explosion at a press conference in front of Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality’s office.

Building the Bayou Bridge Pipeline

Two permits are required for construction of the Bayou Bridge pipeline, which has been proposed by Energy Transfer Partners in conjunction with Phillips 66 and Sunoco Logistics. One is from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and the DEQ, which must sign off on water quality impacts. The second is from the DNR for the project’s last 16 miles of pipeline, which require special attention under the state’s Coastal Zone program.

If built, the163-mile-long pipeline would stretch across south Louisiana from Lake Charles through the Atchafalaya Basin to St. James, a community on the Mississippi River. It would link Louisiana refineries to a major oil-and-gas hub in Texas and connect to larger pipelines throughout North America. The project would be the tail end of Energy Transfer’s Dakota Access pipeline, carrying oil fracked in North Dakota to Louisiana.

The first permit hearing on January 12 in Baton Rouge seemed like a precursor to war. Industry brought out its top guns, including former U.S. Senator Mary Landrieu, who testified on behalf of Energy Transfer Partners. Activists describing themselves as “water protectors” who came from as far as California warned that if a permit is granted, the battle to stop the pipeline could turn the Atchafalaya Basin into the next Standing Rock.

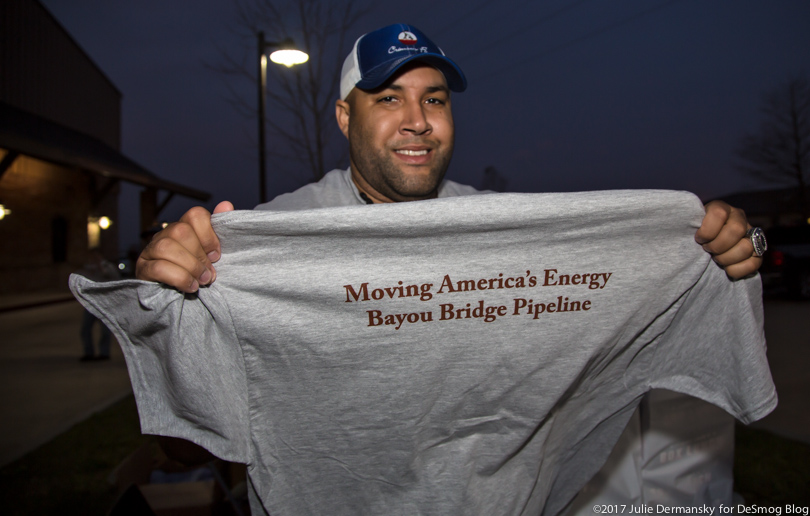

Supporters of the pipeline giving out t-shirts that support the Bayou Bridge pipeline project before the second permit hearing began.

Law enforcement officers next to pipeline opponents at the Louisiana DNR‘s permit hearing for the Bayou Bridge project on February 8.

The Dividing (Pipe)line

Tensions were even higher at the second public permit hearing on February 8 in Napoleonville, Louisiana. At times, civil discourse broke down completely.

Bayou Bridge pipeline manager Cary Farber gives comments at the Louisiana DNR‘s permit hearing on February 8.

Pipeline project manager Cary Farber set a confrontational tone by citing the political climate. “The Bayou Bridge pipeline project is exactly the type of pipeline project that our new president — President Trump — envisioned when he issued the recent presidential orders for infrastructure and pipeline development for our country,” he said.

Farber was followed by politicians who spoke in support of the project, including former Sen. Mary Landrieu. Her testimony reiterated what the politicians who spoke in favor of the project before her said: Pipelines are the safest mode to transport oil and gas, and that the Bayou Bridge pipeline was good for Louisiana’s economy.

Opponents of the pipeline heckling former Sen. Mary Landrieu.

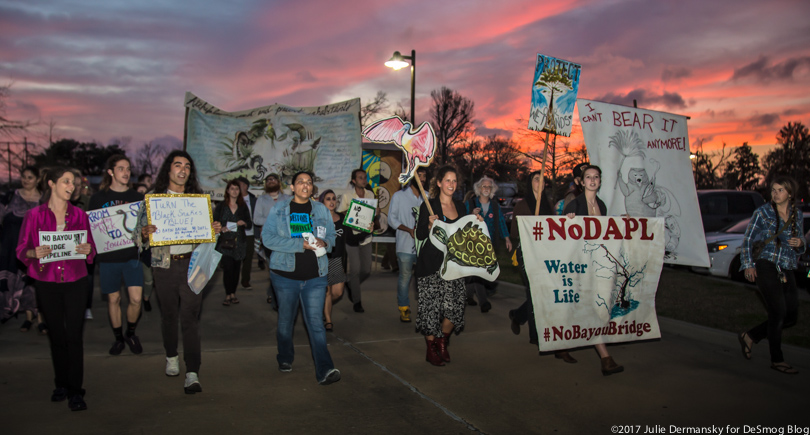

Pipeline opponents at the February 8 permit hearing, many of whom also took to calling themselves “water protectors” in the way that those opposing the Dakota Access pipeline at Standing Rock have been.

Joseph Lopinto, an attorney from the Jefferson Parish Sheriff’s office who spoke on behalf of the National Sheriffs’ Association, seemed to relish enraging project opponents. “The federal government failed to provide local law enforcement [in Standing Rock, North Dakota] with support to control hostile, often violent protesters that caused millions of dollars in property damage and shot at law enforcement officers,” he said, while the pipeline opponents yelled so loud his testimony was almost inaudible.

“We don’t want the same thing occurring here in Louisiana,” he said.

Pipeline Opponents Push Back

Cherri Foytlin, director of the environmental advocacy group Bold Louisiana, objected to Lopinto’s claim that water protectors shot at anyone in Standing Rock, saying that was a lie. She also countered the claim that the pipeline was a great job creator, pointing out that “the jobs will come and go faster than it took to clean the Kalamazoo River,” which is still feeling the impacts of a tar sands spill that happened six years ago.

She further pointed out that Energy Transfer and Sunoco had reported 69 spills in two years and alleged that they had committed human rights violations at Standing Rock. “We are rewarding terrorist [sic] to this country,” Foytlin said before issuing a warning: “We will protect our water. We will protect our people.”

Kathleen Patton, wearing a t-shirt emblazoned with the word “Unarmed,” told the audience she wore the same t-shirt when she went to Standing Rock. She was moved to come to the hearing that evening by President Trump’s remark that the Dakota Access pipeline wasn’t controversial because he hadn’t received a single phone call about it.

“I am here, as are many of you are, to show for the historical record that people are opposed to these pipelines,” Patton said. When she drove to town, she passed a welcome sign as she drove to the hearing that said “Welcome to the Bayou La Fouche Watershed, ours to protect” and urged the DNR to do just that, protect the water by rejecting the permit request.

Jessica Parfait of the United Houma Nation raised concerns about possible damage to sites that hold archeological significance to her tribe along the Bayou Bridge project route.

Environmental groups called for an environmental impact study and more stringent construction standards for the pipeline. And others raised questions about what product would be moved in the pipeline, wondering if it would only be heavy and light crude, as the permit application states, or whether the pipeline also would be permitted to transport Canadian tar sands.

Pastor Joseph from St. James, where the pipeline will end, said his community is already plagued with pollution problems. “People are sick from the smell of the oil tanks. People are sick from the plants that are already there,” he said.

Future of the Pipeline

After the meeting Patrick Courreges, communications director for DNR, told DeSmog that he was encouraged by the turnout. “The public comments can play a role in the shape permits take,” he said.

When I asked if DNR had rejected a pipeline permit request in the last ten years, Courreges said he’d have to get back to me on that. He explained that projects are more likely to be withdrawn than rejected.

Both sides drew their battle lines on the Bayou Bridge pipeline deeper in the sand at the second permit hearing. But at least one claim made at the hearing already is no longer true.

A representative from Philips 66 stated that the company currently has 18,000 miles of pipeline “that move product across this country and do it safely every single day.”

The pipeline explosion in Paradis on Feb 9 nixed the company’s safety claim.

Bold Louisiana Director Cherri Foytlin with Gasland documentary filmmaker Josh Fox, at the site of the Phillips 66 pipeline explosion on Feb 10.

Darryl Malek-Wiley, speaking on behalf of the Sierra Club, asked DNR not to help Texas millionaires become Texas billionaires by approving the Bayou Bridge pipeline.

Main image: Opponents of the Bayou Bridge pipeline walk toward the entrance of Louisiana DNR’s permit hearing on February 8.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts