By Steve Schwarze, University of Montana; Jennifer Peeples, Utah State University; Jen Schneider, Boise State University; and Pete Bsumek, James Madison University.

If citizens have heard anything about the upheaval in the U.S. coal industry, it is probably the insistence that President Obama and the EPA have waged a “war on coal.” This phrase is written into President Donald Trump’s energy platform, which promises to “end the war on coal.”

The often repeated slogan indexes a set of attitudes and assumptions about government regulation and environmentalism. The foremost if the belief that the (liberal, overreaching) federal government has it out for coal and the American way of life that coal supports.

If only the coal industry could get government and its regulations off their backs, the argument goes, thousands of jobs and our economy would come roaring back, a pledge Trump made during his campaign while touring Appalachian coal country. After the election, Trump doubled down on this rhetoric, saying that, “On energy, I will cancel job-killing restrictions on the production of American energy — including shale energy and clean coal — creating many millions of high-paying jobs.”

Yet most analysts agree that the major front in the “war on coal” lies within the market itself. Natural gas production, experiencing explosive growth thanks to the rapid expansion of hydrofracturing, has dealt the biggest blow to King Coal and explains coal’s loss of market share for power generation.

Still, the “war on coal” rhetoric persists. But why? We investigated the public communication strategies used by the industry and found some consistent patterns.

Looking for a lifeline

From the coal industry’s perspective, the war metaphor does capture the situation of an industry under siege and under pressure:

-

Coal production in 2016 fell to historic lows, with a 26 percent drop just in the first half of the year.

-

Six publicly listed U.S. coal companies, including the iconic Peabody Energy, have declared bankruptcy since April 2015.

-

Advocacy group Sierra Club’s Beyond Coal campaign claims 243 coal plants have been shut down and continues to target the remaining 280.

-

Although Trump has vowed to scrap the Clean Power Plan, the reguations would, if implemented, have outsize effect on coal-fired electricity generation.

Casting the coal industry as one under siege provides important cover for industry advocates. This framing allows it to shore up government support for big technological projects such as “clean coal” pilot plants and coal export terminals, while at the same time, it justifies the call to get “big government” out of the way by fighting environmental regulations.

Importantly, the coal industry’s rhetorical playbook isn’t limited to so-called “climate change denial” — although there is clear evidence that the industry has financed several organizations that question the fundamentals of climate science.

Instead, industry campaigns reveal several other rhetorical moves that Big Coal uses to garner support from the public and, perhaps more importantly, from government agencies that could provide a lifeline to an industry in upheaval. We outline five of their most powerful moves below.

1. Industrial apocalpytic

Remember how, following the global financial collapse in the late 2000s, big banks claimed they needed government bailouts because they were “too big to fail”? Big coal makes a similar move when it claims the “war on coal” will lead to an economy in ruins and the collapse of the American way of life.

A quintessential example is “If I Wanted America to Fail,” a five-minute video produced by Free Market America, an organization whose mission is “to defend economic freedom against environmental extremism.” The video circulated on websites of coal-friendly groups during the 2012 presidential primaries, and it equates environmental regulations on energy production with America’s economic failure.

Industrial apocalyptic arguments close off critique, shore up status quo approaches to energy policy and build the specter of environmental regulation as catastrophic.

2. Corporate ventriloquism

Coal also enlists a wide array of voices to speak in ways that advance its interests. We call this corporate ventriloquism. It creates the appearance of broad public support for coal and conflates support for “America” with support for coal through the use of voices ranging from local “grassroots” organizations to national campaigns. Campaigns and organizations such as Friends of Coal, a West Virginia-based advocacy group, and America’s Power, a coal industry trade association, emphasize the monolithic support the coal industry claims to enjoy among everyday Americans.

Corporate ventriloquism also allows the industry to position itself as a grassroots citizen voice, blurring the line between corporation and citizen to seize a rhetorical advantage. In conjunction with conservative foundations, think tanks and sympathetic public officials, the coal industry can use its financial resources to circulate a neoliberal, industry-friendly message and make it appear to be a popular, “common sense” position.

3. The technological shell game

The industry also plays what we call a technological shell game. It misdirects audiences to prior pollution abatement efforts, such as reducing dust and acid rain, to suggest the industry is proactively addressing carbon emissions. But this story conveniently ignores both the problems with carbon capture and sequestration technologies, as well as the history of government regulation and financing needed to make environmental and public health gains.

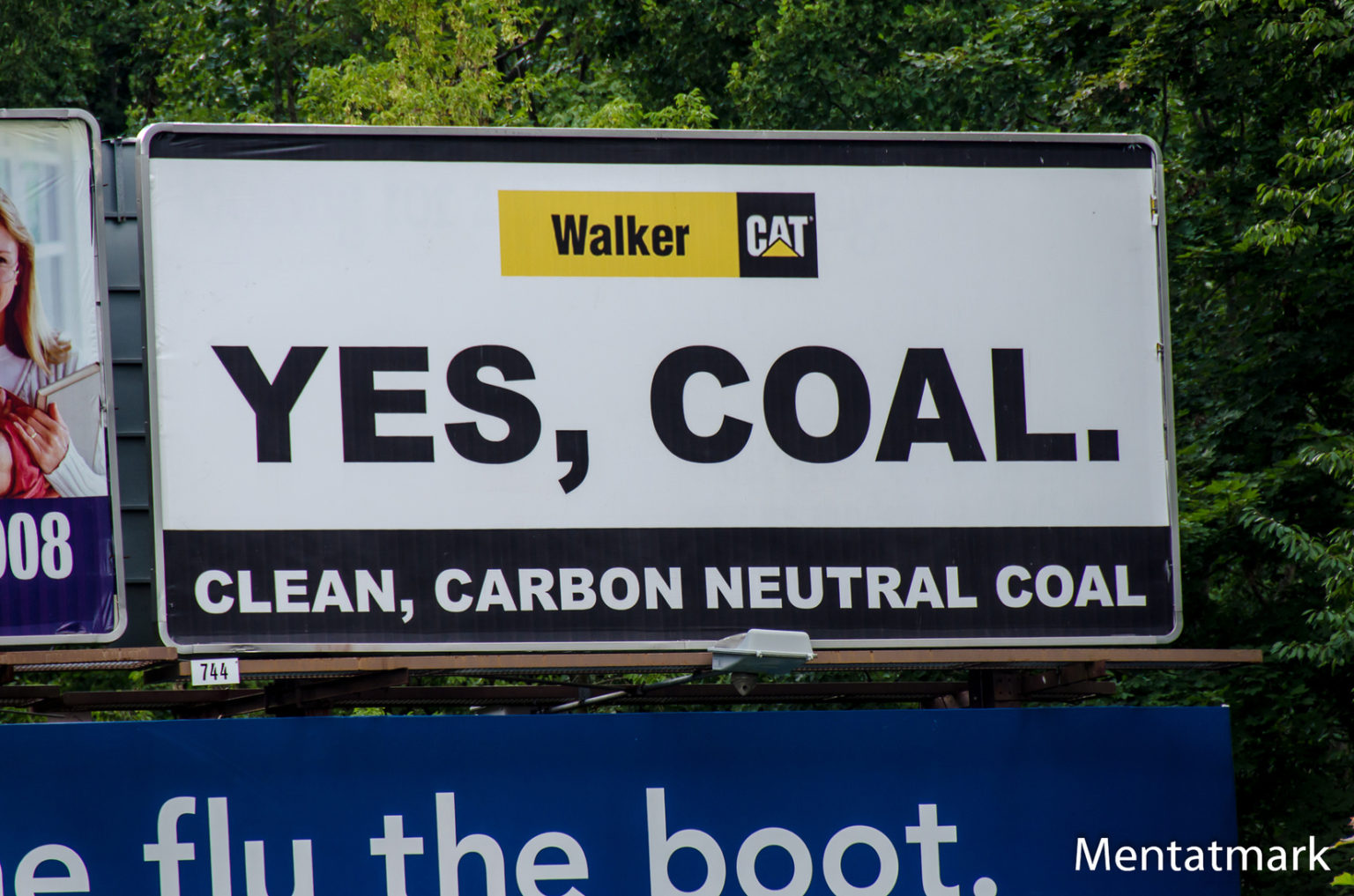

For example, according to the industry-supported group America’s Power website, the coal industry is “ensuring [America’s] future is cleaner than ever before.” The website then points to two “clean coal” plants — the Kemper plant in Mississippi and John W. Turk plant in Arkansas — as technological solutions to the problem of climate change. Yet Kemper has been beset by cost overruns and engineering challenges. Turk’s technologies make it somewhat more efficient than other coal-fired power plants in the U.S. — leading to slightly lower emission levels — but even these levels are well above the emission rates articulated in the now-threatened Clean Power Plan.

When the industry consistently characterizes these two plants as technological fixes to coal’s massive carbon emissions, both of which are heavily subsidized by federal investment and which perform unevenly at best, this is an example of the technological shell game.

4. The hypocrite’s trap

The hypocrite’s trap is a move that gets used with startling frequency against environmental activists, and especially against students advocating for fossil fuel divestment. It silences voices critical of fossil fuel use by pointing to the activist’s own fossil fuel consumption.

We can see this at a celebrity scale when pundits snark about actor Leonardo DiCaprio’s transcontinental flights as a climate activist or former Vice President Al Gore’s electricity bills. At a smaller scale, it’s used to make activists seem naïve about their own complicity in an energy system built on fossil fuels. If you can’t make it without coal and oil, the argument goes, then you can’t say we should divest from those industries.

The counterargument, of course, is that we can critique conditions as they are, even if we also benefit from them. But the hypocrite’s trap is effective because it builds on common conceptions of environmental activists as idealistic dreamers, fossil fuel advocates as hard-eyed realists, and a system that can’t be changed, so why try? The trap turns activists back toward their market role as consumers and silences political dissent.

5. Energy poverty/energy utopia

Given the downturn in domestic markets and environmentalists’ success in branding coal as a “dirty” source of energy, the industry and its allies have attempted to build a “moral” case for expanding the use of coal: its ability to create a utopic future for the world’s poor.

Peabody fashions an entire campaign around this strategy, with images and videos that consistently positions coal as a solution to energy poverty and the key to providing a Westernized version of the good life. Doubling down on the rhetoric of clean coal and the hypocrite’s trap, Peabody’s campaign deflects complicated questions about energy justice and climate change that will be necessary to address in an era of energy transition.

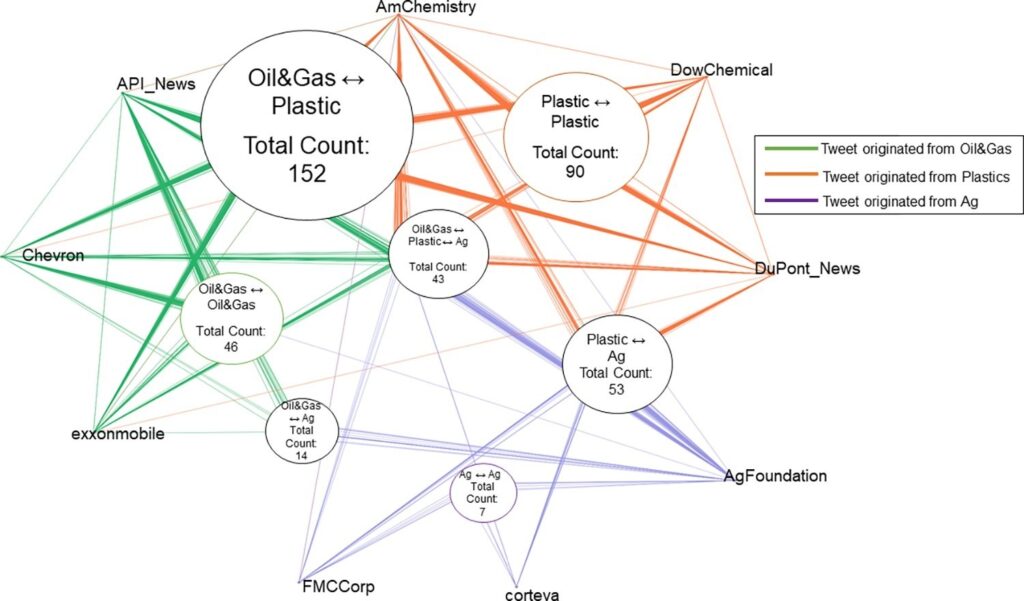

We don’t see these moves as limited to the coal industry — once you understand them, you’ll see them all over the place. They’re used by big industries (oil, gas, nuclear, agribusiness) that see themselves “under pressure” thanks to declining markets or proposed environmental regulations. By naming these rhetorical tools, both academics and activists will be able to do the important work of responding effectively to industry’s standard moves.

Steve Schwarze is a professor at the University of Montana. Jennifer Peeples is professor of communication studies, Utah State University. Jen Schneider is associate professor in public policy and administration, Boise State University. Pete Bsumek is associate professor of communication studies, James Madison University. This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Main image: Photo of a “clean coal” sign taken outside Beckley, West Virginia. Credit: Mark Haller, CC BY–NC–ND 2.0

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts