The shale boom and low prices for natural gas have encouraged a pipeline bonanza in the U.S. Fourteen new pipelines — carrying both oil and natural gas — are either on the drawing board or are nearing completion, adding to the existing 2.5 million miles of energy pipelines in the nation.

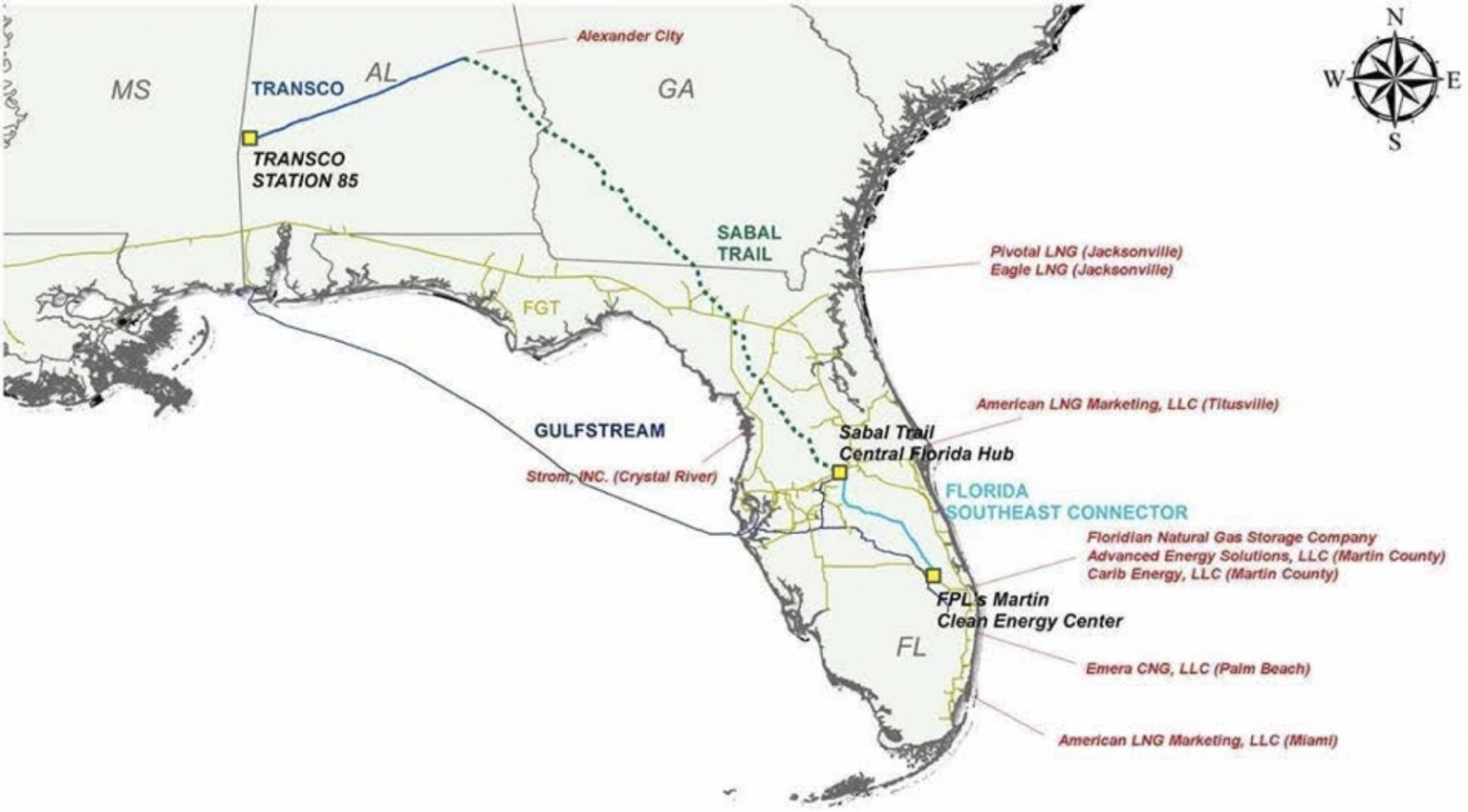

Like many of these pipelines, the Sabal Trail pipeline crosses major watersheds, environmentally sensitive areas, and residential neighborhoods, where property is being seized by eminent domain.

DeSmog previously has examined the growing public opposition to the pipeline, with citizens in Florida and Georgia citing numerous construction violations that could cause environmental destruction.

Opponents of the 515-mile-long pipeline allege that the fast and clumsy installation has followed a fast-tracked approval process, unencumbered by proper government oversight. And they doubt that most of the estimated one billion cubic feet of fracked gas flowing through Sabal Trail each day will even be needed in Florida.

Which raises the question, critics say: Where will most of the gas be heading?

Pipeline ready for installation in Newberry, Florida. Critics say construction could permanently destroy nature preserves and aquifers. Credit: Jesse Hughes

EPA Bails, Lawsuit Filed

In October 2015, four Georgia representatives wrote a letter to FERC to express “serious environmental justice issues” with Sabal Trail, as well as possible health threats to nearby residents, many of whom are low income and African American.

That same month, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) expressed “significant concerns” that the Sabal Trail pipeline could threaten the Floridan Aquifer in Georgia and Florida. Two months later the agency did an inexplicable about-face, dashing environmentalists’ hopes of at least slowing down the project.

James Giattina, director of the EPA’s Water Protection Division, wrote in a letter that the pipeline would temporarily destroy conservation areas, but that the Sabal Trail company promised “to let these conservation areas naturalize to pre-construction conditions and as a result, this land use conversion should not be a significant long-term environmental issue.”

In August, environmental groups Gulf Restoration Network, Flint Riverkeeper, and the Sierra Club filed a lawsuit against the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers for issuing three Clean Water Act permits to allow Sabal Trail pipeline construction.

The suit claims the Army Corps failed to provide proper notice and public participation opportunities and charges that the pipeline project fails to avoid or mitigate adverse environmental impacts. Specifically, the suit claims that the environmental impact statement (EIS) for Sabal Trail was inadequate.

“(The EIS) did not consider how gas was extracted, where it was originating, and the climate impact of power stations along the route,” Merrillee Malwitz-Jipson, a Sierra Club organizer, told DeSmog. “It doesn’t even account for sinkholes.”

In November, a motion for a stay that would halt construction was denied. Malwitz-Jipson says the court may hear their case in early 2017, but a date has not been set.

A protest against Sabal Trail in Gainesville, Florida, in October. Pipeline opponents say few Floridians know about the project. Credit: Stop Sabal Trail Pipeline

Gas for Florida’s Needs, or Export?

Beyond the environmental impacts, opponents of Sabal Trail say the pipeline is not needed, because Florida already has more gas than it needs.

According to the Sabal Trail website, other companies will construct a connecting pipeline, which will complete the delivery to Florida Power and Light (FPL) in Martin County, on Florida’s Atlantic coast. But activists say that it’s unlikely that FPL, which is using $3 billion of ratepayer money to fund the pipeline, will be the only destination for oil flowing through Sabal Trail pipes.

John Quarterman, president of the anti-Sabal Trail group Wwals Watershed Coalition, recalled that Sabal Trail representatives, when pressed at public hearings, maintained that, as a pipeline company they had no idea where gas going through their pipes might end up, a claim that he and other activists find hard to believe.

Chris Pedersen, writing for the industry publication OilPrice.com in October 2014, wrote that Transco and Sabal Trail pipelines could be used to explore new overseas markets for Utica and Marcellus Shale gas.

Sabal Trail opponents say gas flowing through the Sabal Trail pipeline could easily end up at export terminals on the Florida coast. For example, LNG distributor STROM has filed for a Free Trade Permit with the Department of Energy and is proposing two Florida port facilities — one existing and one new — that would eventually source from Sabal Trail.

A Sabal Trail spokesperson told the Atlanta Journal-Constitution just before construction began that the pipeline “will increase energy diversity, security, and reliability to these Southeast markets.”

But, as the Sierra Club pointed out in its opposition to Sabal Trail in 2014, Florida already gets 60% of its electricity from natural gas, and adding a third pipeline would actually decrease energy diversity.

Sabal Trail’s parent company did not respond to requests for comment for this story.

Oversupply of Natural Gas and Infrastructure

Even if, as Sabal Trail suggests, the fracked gas passing through the pipeline will ultimately be used in Florida, that goes against Floridians’ demonstrated desire for more affordable and available solar energy.

Last month, Florida voters rejected Amendment 1, a misleading, utility-funded measure that would ultimately limit the expansion of rooftop solar in the state. And in August, Floridians passed Amendment 4, which provides tax breaks for solar and renewable energy equipment on commercial buildings.

Critics of Sabal Trail and other pipelines say gas infrastructure projects are meant to be a fossil fuel firewall against populist-backed green energy. Environmentalists and even industry insiders say that Sabal Trail is part of a deliberate overbuilding of natural gas pipeline infrastructure for profit, with ratepayers picking up the tab.

As Southeast Energy News reported: “‘The pipeline business will overbuild until the end of time,’ announced Kelcy Warren, CEO of Energy Transfer Partners (ETP), a Dallas, Texas, natural gas and propane company, at an August 2015 earnings call.”

“If you construct a major pipeline to bring gas into Florida, it will only create further dependence on it,” Johanna DeGraffenreid of Gulf Restoration Network told DeSmog. “This new gas transmission may lock Florida into fossil fuels for the next twenty or thirty years, and this is not something Floridians want.”

Main image: A map of the Sabal Trail pipeline route and current and proposed LNG terminals. Opponents say much of the fracked gas will be exported. Credit: Stop Sabal Trail Pipeline

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts