As opposition to the Dakota Access pipeline swells at home and abroad, another pipeline project at the other end of the U.S. is quietly being installed as fast as possible, critics say, displacing residents, threatening water supplies, and racking up alleged construction violations.

And most people in the region — even those in the pipeline’s path — haven’t even heard about it.

Sabal Trail Transmission, LLC, known as Sabal Trail, is using $3 billion of Florida Power and Light (FPL) ratepayer money to build a 515-mile pipeline to transport natural gas obtained via fracking from eastern Alabama to central Florida.

Authorized by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) in February, Sabal Trail is a joint project of Spectra Energy Corp., NextEra Energy, Inc., and Duke Energy.

In Alabama, Sabal Trail would connect to a pipeline network that will move one billion cubic feet of Marcellus-sourced gas from Pennsylvania to Florida, according to the company site, “to serve local distribution companies, industrial users and natural gas-fired power generators in the Southeast markets,” including FPL and Duke Energy of Florida.

Critics of Sabal Trail say the claim of meeting Florida residential and industrial users’ needs for more natural gas is bogus and point to evidence suggesting much of the gas will be sold and shipped internationally.

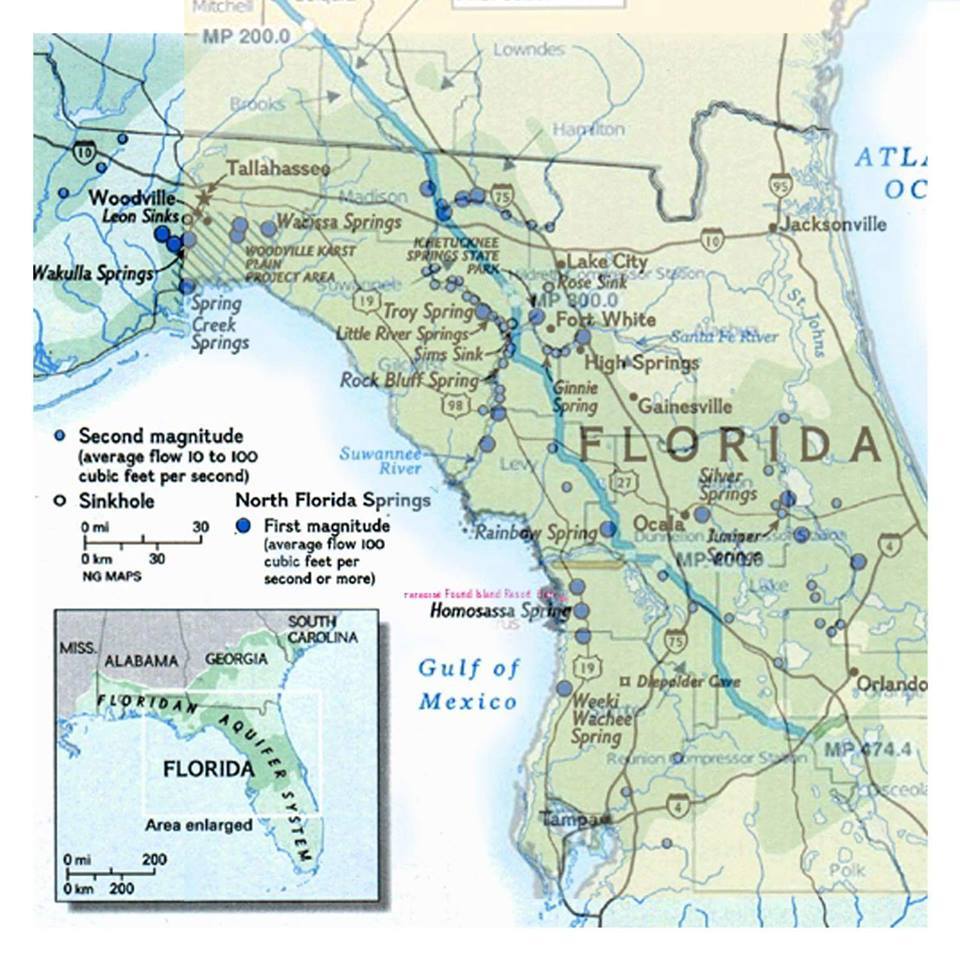

They also say Sabal Trail threatens the fragile limestone surrounding the Floridan Aquifer, one of the largest freshwater aquifers in the world.

And they’re angry that a private company is using eminent domain to force homeowners to sell their properties along the pipeline route.

The comparison between the Dakota Access and Sabal Trail pipelines is apt, critics say, because Enbridge, which is a stakeholder in the Dakota Access pipeline, has announced plans to buy Spectra Energy, one of Sabal Trail’s owners.

The Sabal Trail pipeline route superimposed over the Florida aquifer system. Credit: Stop Sabal Trail Pipeline

Eminent Domain Displaces Homeowners

In April FERC granted Sabal Trail a certificate of public convenience and necessity, giving the company a right to eminent domain. Thanks to a 2005 Supreme Court decision, local governments can force homeowners to sell their properties for private economic development projects.

Along the Sabal Trail project route, several residents have been forced out, some surprised that they were even in the path of the pipeline.

Two Georgia brothers are now faced with paying Sabal Trail’s legal fees in defending their property against the pipeline.

James Bell, one of the brothers, documents the company’s aggressive tactics in a video, saying:

“In my personal opinion I don’t see how a private for-profit company should be allowed eminent domain…I might understand it if it was for the greater good of the country but this is not. And it is certainly not the federal government or the state government building some road or highway.”

Bell and others along the Sabal Trail pipeline aren’t the only private landowners who have been displaced by pipeline companies’ right to eminent domain. The issue has sparked outrage among landowners in the way of the Dakota Access, Transco, and Sunoco Logistics pipeline routes.

Activists Document Construction Violations

Opponents of Sabal Trail say that pipeline construction alone poses a threat to local water resources by releasing hazardous materials and drilling mud into waterways, and they say that several incidents of negligence have intensified those concerns.

In November drilling mud from the Sabal Trail pipeline leaked into south Georgia’s Withlacoochee River, a tributary to the Suwannee River.

John Quarterman, president of the Wwals Watershed Coalition, one of the groups opposing Sabal Trail, tells DeSmog that the incident would never have been reported if he hadn’t seen it while flying over the area on a routine survey.

“I noticed this yellow thing across the river where they were doing horizontal directional drilling. The permitting agency admitted it was a turbidity curtain to contain drilling mud, but they weren’t telling me where the mud was coming from,” said Quarterman.

A Sabal Trail pipeline worker in central Florida. The pipeline will run through conservation areas, under rivers and near springs. Credit: Merrillee Malwitz-Jipson

Quarterman told DeSmog such spills could affect the Floridan Aquifer, and that he wonders whether other discharges are not being reported publicly and whether the drilling could cause central Florida’s fragile underground cave system to collapse.

Merrillee Malwitz-Jipson, an organizer with the Sierra Club in Florida, told DeSmog that activists have documented multiple construction violations in the last six weeks, from plowing down homeowners’ fences to creating sinkholes.

One activist, Ronald Reedy, told DeSmog he observed an enormous piece of equipment, a track hoe, stuck in a wetland area in central Florida on two different days.

“The track hoe was tilting at a 45-degree angle and leaking diesel fuel. You could see the rainbow reflecting from the fuel slick. They’re not supposed to drive these things into the wetlands,” said Reedy.

“When they tried to remove it the next day, they had a man standing between two huge machines with no protection, an accident waiting to happen.”

Quarterman told DeSmog that activists are doing more oversight of construction than the permitting agencies.

Malwitz-Jipson and Quarterman believe that many violations and non-compliance issues are due to the speed of construction to keep the pipeline on track. Construction began in June to meet a May 2017 deadline, which has now been pushed to June 2017.

“They’re slamming this pipe into the ground, under water, as fast as they can and they’re careless,” said Reedy.

Malwitz-Jipson told DeSmog she hopes that enough violations will be documented that the U.S. Congress will step in.

“Several citizens are in constant contact with key representatives who could take serious leadership and tell FERC to shut this down,” she said.

Stay tuned for more on the Sabal Trail pipeline, including an EPA about-face on its environmental impacts, as well as lawsuits against it and conflicting arguments about Florida’s current and long-term need for the natural gas it would bring.

Main image: Water Protectors protest in early December in West Palm Beach, Florida. Credit: Stop Sabal Trail Pipeline

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts