Safety laws meant to protect the American public against oil train explosions, pipeline leaks and other deadly risks have been repeatedly held up by slow-moving federal regulators, a newly released Department of Transportation internal audit has concluded.

The Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (PHMSA) — charged with overseeing 2.6 million miles of pipelines and the handling of a million hazardous material shipments a day — missed deadline after deadline as it attempted to craft the safety rules and regulations that give federal laws effect, auditors from the DOT inspector general’s office wrote in their Oct. 14 report.

“PHMSA’s slow progress and lack of coordination over the past 10 years has delayed the protections those mandates and recommendations are intended to provide,” the report concluded.

Out of 62 rules or studies that PHMSA was legally required to complete by a specific deadline, the agency missed its mandatory deadlines 45 times, auditors wrote, or over 70 percent of the time.

When deadlines were recommended but not required, PHSMA‘s track record was even worse.

“[S]ince 2005, PHMSA has missed deadlines for responding to 115 of 118 NTSB [National Transportation Safety Board] recommendations and 10 of 12 GAO [Government Accountability Office] recommendations,” auditors found.

Sometimes, delays were caused by poor planning, with PHMSA neglecting to coordinate with other federal agencies that might raise safety concerns, like the Federal Aviation Administration and the Federal Railroad Administration, to prevent disputes from arising.

And sometimes, delays emerged because PHMSA failed to take the common sense steps that big projects generally require. “In implementing non-rulemaking mandates and recommendations, program offices rarely: developed plans; established priorities; identified team member roles and responsibilities; created timetables; or justified and documented delays,” the auditors wrote.

The inspector general’s auditors highlighted five ways that the troubled agency could clean up its act, and PHSMA agreed to take most of the steps that the auditors recommended.

But PHMSA‘s response came under fire from public safety advocates, who argued the agency was slow-walking the plans meant to help it speed up.

“I am pleased that PHMSA has accepted the IG [inspector general] recommendations, but the key is in their implementation,” said Rep. Peter DeFazio (D-OR), “and already PHMSA says it won’t be able to implement the recommendations until December 2017, far too long to address such significant concerns and to ensure the health and safety of our communities and the American public.”

The auditor’s probe of PHMSA‘s slow progress was launched in May of 2015, at the request of Rep. DeFazio, the top Democrat on the House Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure.

“In multiple pipeline accident investigations over the last 15 years, the NTSB has identified the same persistent issues–most of which DOT has failed to address,” Mr. DeFazio said at the time. “Each time, Congress has been forced to require PHMSA to take action, most recently in the Pipeline Safety, Regulatory Certainty, and Job Creation Act of 2011. Yet three years later, almost none of the important safety measures in the Act have been finalized, including requirements for pipeline operators to install automatic shutoff valves and to inspect pipelines beyond high-consequence areas.”

A year later, many of those same rules were still not finalized, the auditors found.

The agency blew past deadlines when it came to steps to address oil train safety and rules on responding to spills of oil and other hazardous materials, auditors found.

Pipeline standards also moved slowly. Federal safety experts have long recommended that gas pipelines connected to apartment buildings and other multi-family residences be equipped with an automatic shut-off valve that that can stop a gas leak from turning into a deadly explosion.

Federal law required PHSMA to decide whether new or upgraded pipes must be equipped with the valves, which cost a couple hundred bucks, within two years. But nearly three years after its deadline had run out, PHMSA still had yet to make a move.

And a proposal to map the nation’s network of tens of thousands of miles of so-called “gathering lines,” or smaller pipes that connect oil and gas wells into large interstate pipeline systems, also remains uncompleted.

“PHMSA should at least know what’s out there: how many gathering lines, what the pressure is, how old they are and what the risks are,” Susan Fleming, director of the physical infrastructure program at the Government Accountability Office, told Politico last year.

PHMSA‘s slow progress has long frustrated lawmakers. For example, a 2011 law required PHMSA to conduct 42 rule-makings and studies — but more than a quarter of those projects remained incomplete as of July of this year. “We cannot achieve the intended objectives of the Pipeline Safety Act until it has been fully implemented,” Energy and Commerce Chairman Rep. Fred Upton told The Hill in March.

Last year, investigative reporters from Politico published a damning look at PHMSA‘s track record and why it’s been so slow to move. The agency is underfunded and understaffed, they found, writing that its annual budget of $145.5 million is “less than what the Pentagon spent on a single jet engine maintenance contract last year.”

It’s also closely tied to the industries it’s supposed to regulate — in part because of PHSMA‘s very design. By law, new PHMSA rules must be reviewed by advisory committees that in practice have become heavily weighted with industry reps, Politico found. “Advisory committee meetings are largely friendly affairs, a review of thousands of pages of transcripts shows, almost wholly devoid of resistance to industry-driven projects that craft voluntary standards for PHMSA,” reporters Elana Schor and Andrew Restuccia wrote.

And while PHMSA is one of the Department of Transportation’s smallest agencies — despite its life-or-death responsibilities — problems run deeper than just a lack of staff or the agency’s high turnover rate. There is also a culture inside the agency that Politico labeled a “can’t do” mentality.

“They’re understaffed to provide adequate oversight of the industry, but I don’t believe they’re understaffed to move a regulatory framework,” Jim Hall, former head of the National Transportation Safety Board told Politico. “They’ve just lacked the will to do so.”

Nonetheless, PHMSA‘s to-do list keeps on growing.

One year ago, a massive leak began at the Aliso Canyon gas storage site near Porter Ranch, California. It ultimately spewed almost 100,000 metric tons of methane, a powerful greenhouse gas, into the atmosphere and drove thousands of nearby residents and businesses to evacuate the surrounding area for months.

This summer, a newly enacted law, the Protecting our Infrastructure of Pipelines and Enhancing Safety Act of 2016 (PIPES Act), charged PHMSA with launching over a dozen new studies, reports, and rule-makings — including figuring out how to prevent more leaks from storage facilities like Aliso Canyon.

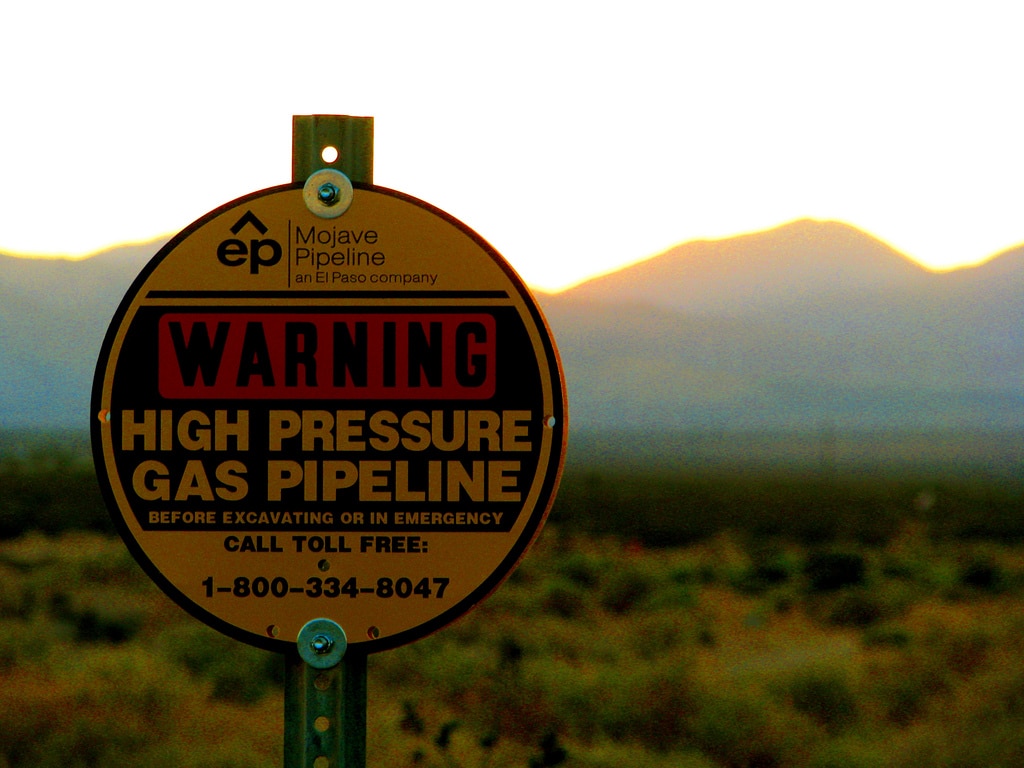

Photo Credit: Rennett Stowe: High Pressure Pipeline, via Flikr.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts