New and protracted battles in the hydraulic fracturing (“fracking”) war are breaking out across Pennsylvania and other states near the Marcellus Shale over pipeline companies’ use of eminent domain.

The fiercest battle pits Philadelphia-based Sunoco Logistics against homeowners in the path of a pipeline that crosses Pennsylvania. In a controversial move invoking eminent domain, Sunoco aims to seize private lands to make room for a pipeline extension that would move highly volatile liquids (HVL) used in the making of plastics from the Marcellus Shale region to eastern Pennsylvania.

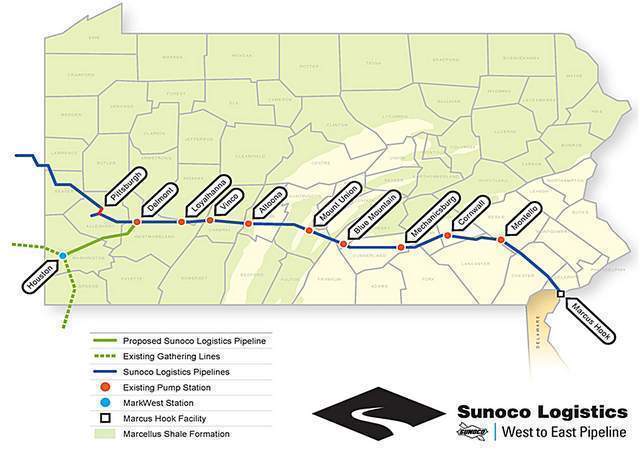

With an air of inevitability, opponents say, Sunoco is planning to move ahead with Mariner East II, a retrofit and extension of an existing east-west pipeline that was once used to ship gasoline westward from Philadelphia’s refineries.

The converted pipeline would move 70,000 barrels of highly volatile liquids, including butane, ethane, and propane, across Pennsylvania daily. Its terminus would be the Delaware-Pennsylvania border, at the company’s Marcus Hook facility, which Sunoco is also transforming to handle natural gas products, and where the company is building a plant to convert propane into propylene, a building-block commodity of petrochemicals.

Natural gas from the northeast has traditionally been sent to Louisiana and Texas to be processed for domestic use or shipped overseas. In moving highly volatile natural gas liquids, byproducts of natural gas production, Sunoco Logistics is aiming for a faster route to a coast. Using its Marcus Hook facility would give the company a new source of revenue and make use of the expansion of natural gas production in the Marcellus Shale.

Sunoco’s primary market for these natural gas liquids is a refinery in Scotland that manufactures plastics.

Claiming “Public Benefit” for Private Profits

The potential windfall for Sunoco may be the reason for what opponents say are strong arm tactics to seize private property in the path of the pipeline extension, tactics that include invoking eminent domain, even though it’s a private, for-profit company rather than a government entity, and even though, they say, it has not proven that the pipeline would contribute a “public benefit.” Both conditions are traditionally required for landowners to forfeit property in eminent domain disputes.

Sunoco argues that their use of eminent domain is justified because Mariner East II will provide a public benefit by providing extra propane to residents in offload points throughout the state.

Sunoco’s Mariner East II pipeline crossing Pennsylvania. Image credit: Sunoco Logistics

And the company has won the latest battle. In July, a Pennsylvania state appeals court ruled that Sunoco was operating as a public utility and that the Mariner East II pipeline is both interstate and intrastate and was therefore subject to jurisdiction by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission and the Pennsylvania Public Utility Commission (PUC).

The majority opinion in the 5-2 decision gave Sunoco a certificate of public convenience for 17 counties along the path of Mariner East II.

Alec Bomstein, a senior litigation attorney with the Philadelphia-based Clean Air Council, which was a plaintiff challenging Sunoco’s public utility status last year, scoffs at the public benefits Sunoco claims to be providing.

“The primary purpose of Mariner East II is, one, to make money for a for-profit, private corporation, and two, to export natural gas products overseas,” Bomstein tells DeSmog. “Saying that they’re going to help residents by providing an additional 70,000 barrels of propane a day is a red herring, because that kind of capacity is not needed in the state.”

Bomstein adds that calling Sunoco Logistics a public utility is absurd because it is not regulated nor held to the standards of a utility.

Sunoco Logistics, which is owned by Energy Transfer Partners, did not respond to DeSmog’s requests for comment.

The Clean Air Council and other opponents of Mariner East II decry Sunoco’s reliance on an ancient document to claim its status as a public utility, a move that wouldn’t carry weight in another state. In 1930 the Pennsylvania Public Service Commission, a precursor to the state PUC, granted the Susquehanna Pipe Line Company a certificate of public convenience, allowing the company to build a pipeline to move gasoline from Philadelphia refineries to western counties.

Beyond crying foul over Sunoco’s evoking of eminent domain, homeowners and municipalities are worried about safety.

The Danger of Transporting Highly Volatile Liquids (HVL)

Highly Volatile Liquids (HVL) including ethane, propane, and butane are flammable gasses when released into the air. The gas is also heavier than air, which means it doesn’t disperse easily.

Nevertheless, highly volatile liquids are classified as liquids by the federal government. Because of this, operators don’t need to develop area-specific response plans for leaks. That’s something that worries Eric Friedman, an officer of a homeowner association in suburban Philadelphia. Sunoco has attempted to seize open space in his development that would put a pipeline extension literally a few hundred feet from existing homes.

“Sunoco has a generic response plan for leaks,” Friedman tells DeSmog. “It’s to go upwind, walk, don’t drive, a half-mile or more. That’s it. Well, how do you know there’s a leak when you can’t smell the gas, and how do you know which way the wind is blowing?”

Friedman adds that many people live within the so-called blast zone of the proposed pipeline. “This situation has left many people completely voiceless and defenseless with respect to their ability to mitigate the risk of highly volatile liquids infrastructure.”

And then there’s Sunoco’s abysmal safety record. Documents at the United States Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (PHMSA) show that Sunoco has the worst safety record of 1,518 active pipeline operators that report operating data to PHMSA.

Friedman, who along with his homeowner board of directors are looking at ways to fight the company’s actions in the Delaware County court, says Sunoco offered no money for the land.

He agrees with Bomstein that the “public good” defense used by Sunoco to seize land is absurd.

“There’s no economic benefit to this area. It will be economic blight. Ancient trees will be torn down. Our homes will be worth less because of the danger of leaks,” Friedman said.

Pipeline Property Battles on Several Fronts

The controversy over whether a private company can take private land to build pipelines is not settled.

There are many fronts to the pipeline war in several states, including upcoming court cases and possible legislative action.

In February, the Kentucky state supreme court upheld a lower court ruling which found a pipeline company is not a public utility and therefore could not use eminent domain for natural gas liquids pipelines.

Fifteen Ohio families are fighting Texas pipeline company Kinder Morgan’s use of eminent domain, claiming that seizure of land by private pipeline corporations violates the Ohio Constitution’s strict protection of private property rights.

In Pennsylvania, Friedman is focusing on informing General Assembly members and those running for local and state office about the risks. He says the eminent domain issue may, as in Kentucky, be decided in the state supreme court. If that happens, the court will have to decide how broad the power of eminent domain is in the state, and define what constitutes public good.

And with oil and gas pipeline construction projects on the rise across the nation, observers on both sides will eagerly await the results.

Photo credit: Anti-fracking protestors at a rally in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in July 2016. Suzanne Bobosky, used with permission.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts