Eleanor Fairchild, an 82-year-old grandmother who owns a 425-acre ranch outside of Winnsboro, Texas, has advice for anyone who is asked to sign a contract by a company that wants to build a pipeline to transport tar sands oil on their land: “Don’t sign it.”

During a recent visit to her ranch, I saw the damage to her land caused by the installation of TransCanada’s Gulf Coast Pipeline, which is the original southern route of the Keystone XL pipeline before the project was broken into segments.

I first met Fairchild in October 2012, a few days after she was arrested, along with environmentalist actress Daryl Hannah. The two had stood in the way of land-moving vehicles on Fairchild’s land where TransCanada had started clearing trees and readying a right-of-way to install its pipeline. At that time, Fairchild was refusing to make a deal with TransCanada, but the company moved forward with clearing her land anyway.

Video: Eleanor Fairchild on Eminent Domain

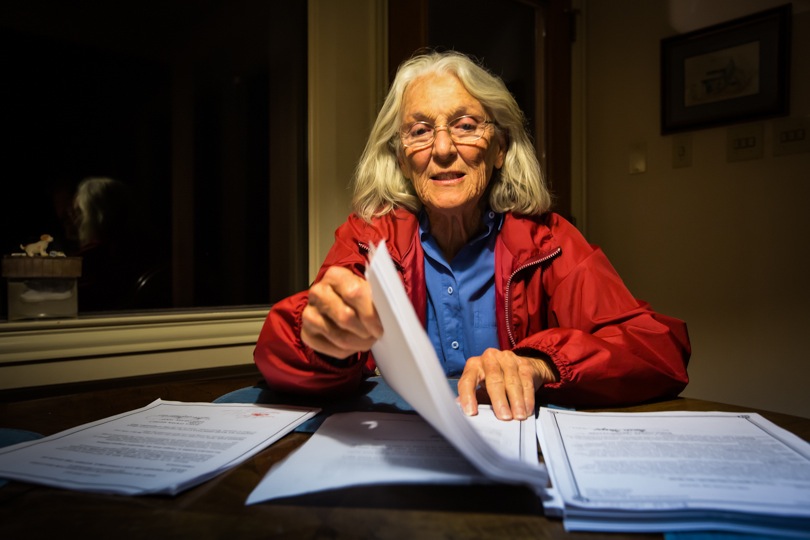

My first visit coincided with TransCanada filing a strategic lawsuit against public participation (SLAPP suit) that accused Fairchild — along with activists in the Tar Sands Blockade — of being eco-terrorists. I took a picture of her behind the stack of paperwork that was over an inch thick. She thinks the use of SLAPP suits by companies like TransCanada should be forbidden because their sole purpose is to try to silence critics.

Eleanor Fairchild flipping though the SLAPP suit. ©2012 Julie Dermansky

Fairchild on the TransCanada’s right-of-way during the construction of the Gulf Coast Pipeline. ©2012 Julie Dermansky

The charges lingered until late 2014, when she reached an agreement with TransCanada. Besides settling on a dollar amount for the company’s use of a right-of-way through her property, TransCanada dropped the charges and apologized for calling her an eco-terrorist. The apology was a condition Fairchild insisted on before any agreement would be signed.

Fairchild now regrets that she made a deal with TransCanada.

“Once I signed an agreement, TransCanada seemed to think it could get away with ruining my property,” she said.

But she plans to do everything in her power to stop that from happening.

During my first visit to Fairchild’s ranch, we went to the easement where workers with land-moving machines were digging. We walked across the creek to the other side where a wide swath of trees running the length of the right-of-way had been cut down to make room for the pipeline.

Fairchild warned that clearing the trees would cause erosion issues, and she was right. A hole large enough for her to stand in opened up in January 2013.

Eleanor Fairchild in a hole that opened up on her land due to erosion caused by the KXL pipeline installation. ©2013 Kathy Redman

TransCanada filled in the hole and did some work to strengthen the banks of the creek that the pipeline installation had weakened.

But Fairchild believes that whatever work the company did ended up making problems worse.

“TransCanada sends people who don’t know what they are doing,” she told me.

The contractors sent to plant trees admitted it was their first time ever planting trees. “Only 30 of the 200 trees that were planted are still alive,” Fairchild said.

Four years later, Fairchild and I went back to the same spot we visited in 2012. This time we couldn’t walk down to the creek because the banks were covered with loose rocks too dangerous to walk on.

Fairchild recounted what a horror it was for her to find TransCanada had dumped truckloads of rocks down the banks and into the creek bed to deal with the erosion that had worsened since the company’s first restorative attempt in 2013. She let the company know its first effort to stop the erosion had not worked, and asked them to try again. But she never imaged the company would move forward without discussing with her what they planned to do.

TransCanada maintains that covering the banks of the creek with medium-sized rocks, known as rip-rap, is a good solution to stabilize creek banks. But Fairchild doesn’t believe it will work. The rocks are continuing to sink into the sand, making the banks more unstable than they had been.

She is not the only one with a negative assessment of TransCanada’s restoration efforts. Earlier this year, an inspector sent by TransCanada to check the status of erosion on Fairchild’s land, told her the work TransCanada is doing to fix her land is patchwork that ultimately won’t do the job. In his opinion, all the rip-rap needs to be removed and a drain system constructed, like one TransCanada installed for one of her neighbors whose land had similar problems. He also confirmed that a deep cut that formed alongside the right-of-way was caused by remediation work already done.

But another TransCanada representative had told Fairchild the company was not responsible for the cut because it wasn’t part of the right-of-way.

Rocks lining the banks of a creek on Fairchild’s land that the Gulf Coat pipeline crosses. ©2016 Julie Dermansky

Agreements between TransCanada and landowners require the company to return property to its original condition, or as close as possible to it.

“The banks and the creek bottom didn’t have rocks before the pipeline installation, and now they do. There were no rocks anywhere in that area, it was just solid sand.” Fairchild said. “How can this be considered returning my land to its original condition?” she wonders.

TransCanada doesn’t deny that some landowners have complaints. The company’s media specialist Matthew John told me that more than 90% of the landowners are satisfied with restoration efforts. “Restoration along the Keystone System right-of-way has been progressing well,” John claimed in an email to me. As for issues on Fairchild’s land, the company is still working with her on that, according to John.

After Judah Lopez, the TransCanada land representative for Fairchild’s area told her the company would address the problems on her land — but that there was no money to get to them this year — Fairchild wrote to TransCanada’s CEO and the company’s Dallas office to let them know waiting until next year was not acceptable.

In response to Fairchild’s letter, Andrew Craig, the land manager for the Keystone Pipeline, came to take a look with a team. He agreed to fix the cut in her land this fall, but her request to take the rip-rap away was denied. “I am pleased that things look better,” he wrote Fairchild following his visit.

Things didn’t look good to me. I wondered where landowners like Fairchild could turn after the government green lighted a pipeline company’s eminent domain use of their land, and then that company didn’t restore it to near its original condition.

I asked the US Department of Transportation Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (PHMSA) if it has any role in helping a landowner in a case like Fairchild’s.

PHSMA representative Damon Hill explained in an email that it isn’t PHMSA’s job to handle complaints from landowners unless the complaint is directly related to the pipeline, for example a spill incident.

“We can only hope they hire people who know how to do the job”

So what agency should a landowner turn to if a pipeline operator damages their land, if not PHMSA? Hill suggested the landowner try a state agency, but could not say which one. In a follow-up conversation*, he also added that the landowner could sue the pipeline company.

I contacted the Texas Railroad Commission, the agency that regulates the oil and gas industry in Texas, about Fairchild’s situation and asked if it handled landowners’ complaints about damage caused by pipeline companies. Ramona Nye, a spokesperson for the commission, referred me to PHMSA.

Next I tried the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE). I was unable to get a response from the Fort Worth office, which deals with creeks in the Winnsboro area, but a spokesperson in the Galveston office, Kristi McMillian, returned my call. The Corps would like to be able to respond to all the complaints concerning damage to creeks caused by pipelines, she said, but its manpower is limited.

I asked Smith if TransCanada needed to use licensed contractors to do restoration work when a problem arose along a creek after the pipeline installation, as in Fairchild’s case.

“We can only hope they hire people who know how to do the job,” she said, but there is no license required for a contractor to do restoration work on the creek banks.

Fairchild reached out to the USACE after my June visit. She spoke to Corp compliance officer David Madden on June 16* about the situation on her land. He told her he would look into it and get back to her. A couple of months later, Fairchild called him again to ask if anyone was planning to have a look. Ryan told her he had passed on her information and would check to see on the progress.

Fairchild bristles when she hears Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump talk about how people can get rich from eminent domain.

“It’s not true,” she said. “That is a lie.”

If a company can claim it is entitled to use eminent domain to get a project built, you can either make the best deal you can with that company, or the government will allow the company to take your land anyway, she said.

My takeaway from Fairchild and other landowners who have opposed the pipeline from the start — and have had to deal with issues similar to Fairchild’s — is that once a pipeline company decides it is going to take your land, you are on your own.

“It just isn’t right how these companies are allowed to treat people,” Fairchild told me. “But if TransCanada thinks it can just wear me down and I’ll stop fighting, they are wrong.”

She plans to do whatever its takes to get TransCanada to comply with not only its contract with her but also the federally mandated rules, which obligates the company to restore her land to its original condition or as close as possible to it.

Video: Eleanor Fairchild on David Daniel and the fight against tar sands pipelines

* This story has been updated to clarify dates and names of agency contacts.

LEAD IMAGE: Eleanor Fairchild standing in a cut on her land caused by erosion connected to the Gulf Coast Pipeline that TransCanada has agreed to fix. ©2016 Julie Dermansky

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts