One week ago, Peabody Energy cried uncle.

The world’s largest privately-owned coal producer filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection, following Arch Coal, Alpha Natural Resources, and Patriot Coal in begging the United States Bankruptcy Courts for mercy.

It would be easy for climate advocates to cheer the occasion as yet another signpost along the hard-fought road to a carbon-free future. But, unfortunately for many involved, Peabody’s bankruptcy could leave many vulnerable parties—from coal workers to Navajo tribes to students in St. Louis— suffering further.

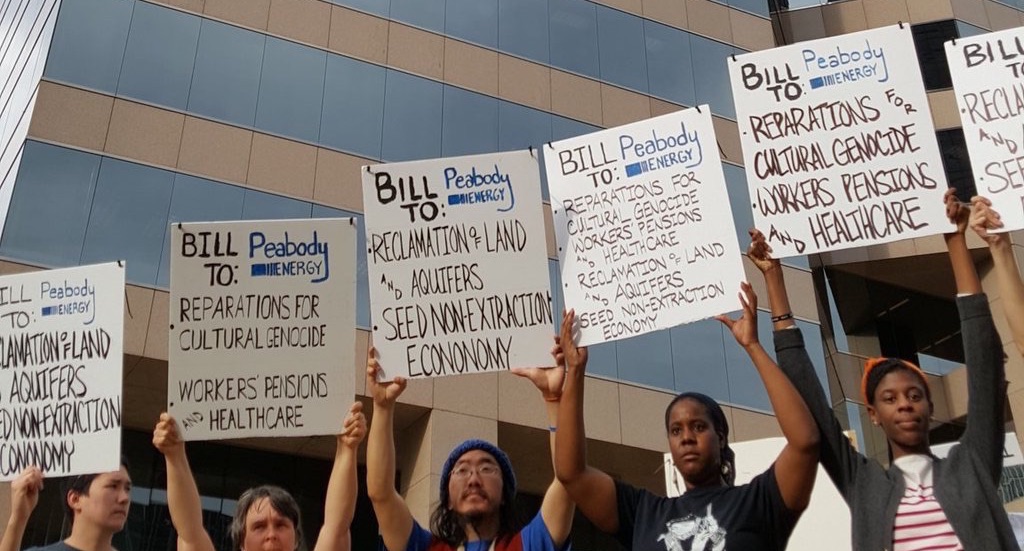

Which is why activists from impacted communities gathered on Tuesday in St. Louis, home of Peabody’s headquarters, to demand that a “Just Transition Fund” is endowed as part of the bankruptcy proceedings before the “golden parachutes” are given out to reckless executives and the loans are repaid to the reckless banks that kept funding Peabody’s speculation.

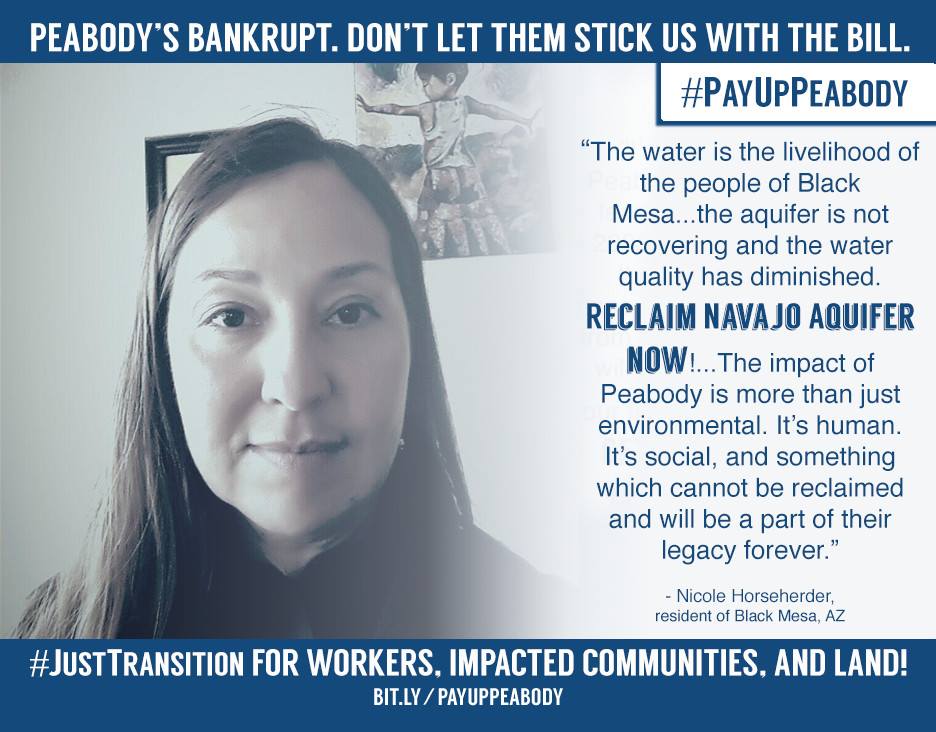

Members of the Dineh (Navajo) Nation drove two days from the Black Mesa to join up with mine workers and residents from communities impacted by Peabody’s extraction in Southern Illinois and with teachers and students from St. Louis. The diverse alliance all have one thing in common: Peabody’s operations have hurt their lives and livelihoods.

“For over forty years, Peabody has been involved in displacing Dineh (Navajo) people on Black Mesa. Peabody has caused the continuous suffering of Dineh people,” said Danny Blackgoat of the Black Mesa. The company’s Kayenta mine has carved up tribal lands on the plateau, polluted natural springs that the Navajo Nationa and Hopi tribe depend on, and drained the critical Navajo Sandstone Aquifer.

In Southern Illinois, the picture is no prettier, as Judy Kellen of Rocky Branch describes.

“I have felt each one of Peabody’s mining blasts from my house across the street. I have breathed in the toxic dust. The ground that Peabody has mined is not farmable. The water is ruined and streams are gone. Miners are out of work. And we are still here. Our experience shows that mining corporations do not have a problem sacrificing anything or anybody that gets in the way of their bottom line.”

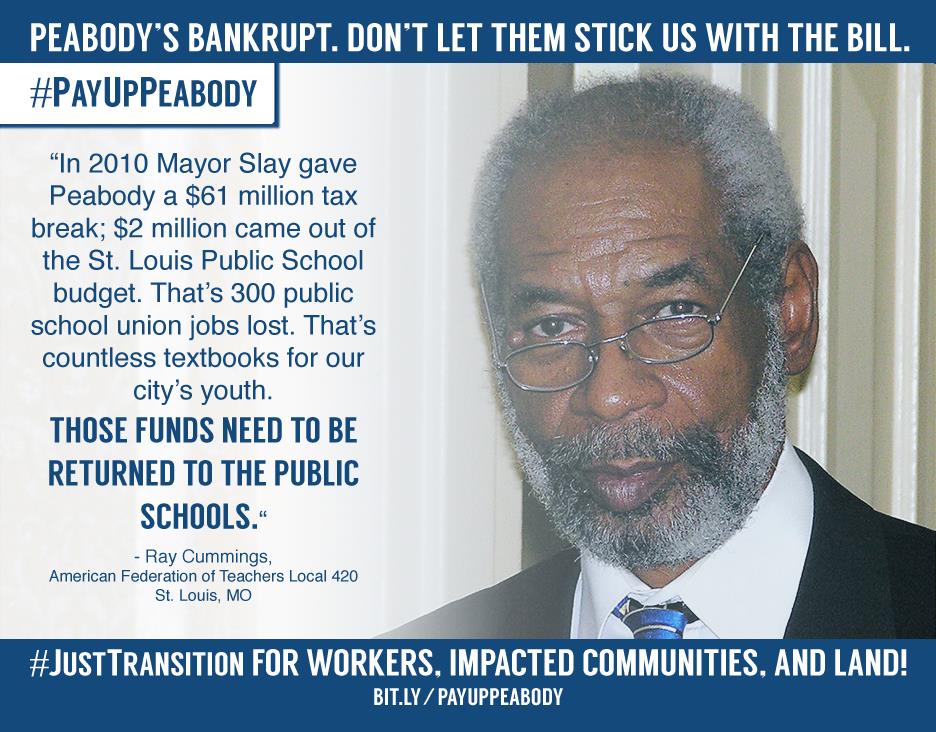

Even in St. Louis, safely removed from the resource curse of coal extraction, there are economic impacts felt. The city infamously granted Peabody a $61 million tax break in 2010 to help secure another ten year lease for their headquarters, covering some of the cost by reportedly pulling funds from public schools. “In 2010 Mayor Slay gave Peabody $2 million out of the St. Louis public school budget,” explained Ray Cummings, VP for Political Education at the American Federation of Teachers St. Louis Local 420. “That’s 300 public school union jobs lost. That’s countless textbooks for our city’s youth.”

On Tuesday, these groups converged first on Peabody headquarters and then City Hall to demand the coal company be held accountable through the bankruptcy process for those harmed.

How Peabody Can Ignore Innocent Victims Through Chapter 11

“Filing for bankruptcy” is often misconstrued as the last gasp of a dying business. That may be the case for a Chapter 7 liquidation, but because of the protections afforded by U.S. bankruptcy law, a Chapter 11 filing is an attempt at resuscitation. At least to keep the ailing business alive for long enough to take care of top management and the big banks that are owed money.

In fact, Chapter 11 not only allows for a company to keep operating, the particulars of the provision encourage it to help pay off financiers. According to Peabody’s statement announcing the bankruptcy, “all of the company’s mines and offices are continuing to operate in the ordinary course of business and are expected to continue doing so for the duration of the process.”

So no respite from the coal dust or water draws in the Black Mesa, or from the blasts and black lung in Southern Illinois.

“Our biggest fear from the beginning was Peabody leaving us in the dust, and that fear is growing stronger,” said Kellen. “If we could afford to leave, we would. But we cannot. This bankruptcy will send shockwaves throughout our already poor and unstable local economy, which is centered around coal mining. This bankruptcy positions Peabody to abandon their responsibilities to my community.”

Activists on the steps of City Hall. Credit: Bret Gustafson on Twitter.

Meanwhile, in bankruptcy court, Peabody will ask permission to cut jobs, benefits, and pensions for workers. They will also try to wriggle out of their legal obligations to clean up or reclaim their mines (because in many cases states have allowed them to “self-bond,” Peabody hasn’t yet paid a dime into many of the bonds that are intended to pay for the strip mined land to be restored).

As Jenny Marienau wrote at Common Dreams, “If we can learn anything from recent bankruptcies in the sector, Peabody’s chapter 11 is simply a new variation on the company’s habit of externalizing the costs of its dirty and destructive business practices onto its workers, impacted communities and the environment.”

Marienau goes on to give an example:

Last year, Alpha Natural Resources (don’t let the name fool you – it’s a coal company) filed for bankruptcy, laid off 4,000 of their workers, and is now working to cut the insurance benefits of nearly 5,000 retired workers and their families. Meanwhile, they are guaranteeing bonuses of a whopping $11.9 million for a handful of top executives. In July of 2015, a bankruptcy court approved a similar request from Patriot Coal “protecting” $6 million in bonuses for executives and middle managers as they worked through their own Chapter 11.

What Would a More “Just” Bankruptcy Look Like?

The protesters outside Peabody’s headquarters and City Hall on Tuesday presented both an invoice—for $14 billion to pay into a “Just Transition Fund”—and a set of demands to the decisionmakers in the bankruptcy court, including:

- Fully fund promised Peabody and Patriot coal worker pensions and health care plans.

- Put an immediate stop to the forcible relocation and harassment of Diné (Navajo) people in northern Arizona and provide full reparations for cultural genocide caused by Peabody.

- Guarantee full funding for clean-up and full reclamation of all mined lands and polluted and depleted aquifers used by Peabody.

- Prioritize payouts to shareholders for communities negatively impacted by Peabody’s practices in areas left stranded in the bankruptcy. Support communities as they transition from coal-based economies toward renewable energy and self-sufficiency. Support healthcare funds for communities in and adjacent to mining and coal-processing areas.

“The bankruptcy court will want to pay CEOs first, but really those resources should go to the people directly affected. Not the tribal governments—but the people affected by Peabody’s mine, the people who have resisted forced displacement; the people Peabody has harassed for decades,” said Blackgoat.

Beyond simple reparations for the harm inflicted and damage caused, the activists laid out a vision for how to use the money to invest in a better future for the communities that have been anchored to Peabody’s coal. This vision includes re-employment training and economic redevelopment plans to help transition away from coal extraction toward economically and environmentally sustainable local economies.

Kellen explained, “For well over a century, people in Southern Illinois have paid the price for coal companies. That must end today. We need guaranteed quality clean up of the land, so we can farm again. We need job training and investment in sustainable employment. No form of fossil fuel industry fits this call.”

The groups are calling upon the public to sign their petition to make Peabody pay up.

Top images: Kelly Hayes on Twitter

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts