This is a guest post by Rhiannon Fionn, an independent investigative journalist and filmmaker in post-production on the documentary film “Coal Ash Chronicles.”

“I’m fighting for my kids and my neighbors,” says a determined Amy Brown.

Brown and hundreds of other North Carolina residents have been using only bottled water for the better part of a year now for cooking, drinking, hygiene and even for their pets. Like Brown, most of those residents live near impoundments of coal ash — the waste product created when coal is burned for electricity.

Now residents are learning that the “do not drink” orders placed on their well water supplies have been lifted by state officials. That decision has provoked fear and confusion among residents and some experts about the safety of their water supply. “This news makes me feel like we’re not getting anywhere,” said Brown, before her voice wavered with emotion.

In April 2015, the state began notifying residents their water wells were contaminated, many with the carcinogen hexavalent chromium and vanadium, which is known to harm kidneys and affect blood pressure.

Residents were issued the “do not drink” notices by the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality. Duke Energy’s coal ash impoundments were suspected as the cause of the contamination and the company was compelled by the state legislature to provide bottled water.

But last Monday, March 7, during a county commission meeting in rural Lee County, state officials announced most of the “do not drink” orders were being withdrawn.

“The first I heard of it was when the media contacted me,” Brown said.

Tom Reeder, the Assistant Secretary of the N.C. Department of Environmental Quality, is one of two state officials who spoke to the Lee County Commission.

“Every major city in North Carolina has either [hexavalent chromium] or vanadium in it in levels above what people have been calling these ‘action levels’,” he testified. “That’s Winston-Salem, that’s Raleigh, that’s Asheville, that’s Charlotte, that’s Greensboro, that’s Wilmington – every city we have this data for exceeds those levels.”

Reeder claimed other major cities in the U.S. have hexavalent chromium and vanadium in their drinking water, purportedly from natural geological sources, and in some cases the levels present in drinking water were higher than those found near coal-ash sites in North Carolina.

Listen to or watch Tom Reeder’s testimony here.

Following Reeder’s testimony, Commissioner Robert T. Reives berated him for not speaking specifically about the drinking water in his county and asked, “Why were we told not to drink the water?”

“You’ll have to ask Dr. Williams that,” Reeder responded, referring to Dr. Randall Williams, the state health director. “I’m telling you from a regulatory perspective, your water meets the requirements of the federal Safe Drinking Water Act,” Reeder said.

Reives continued asking questions as Reeder walked away, throwing up his hands and saying, “I didn’t send the letters.”

Environmental groups say that pointing out how municipal water is also contaminated doesn’t mean the state should withdraw public health protections from citizens using well water.

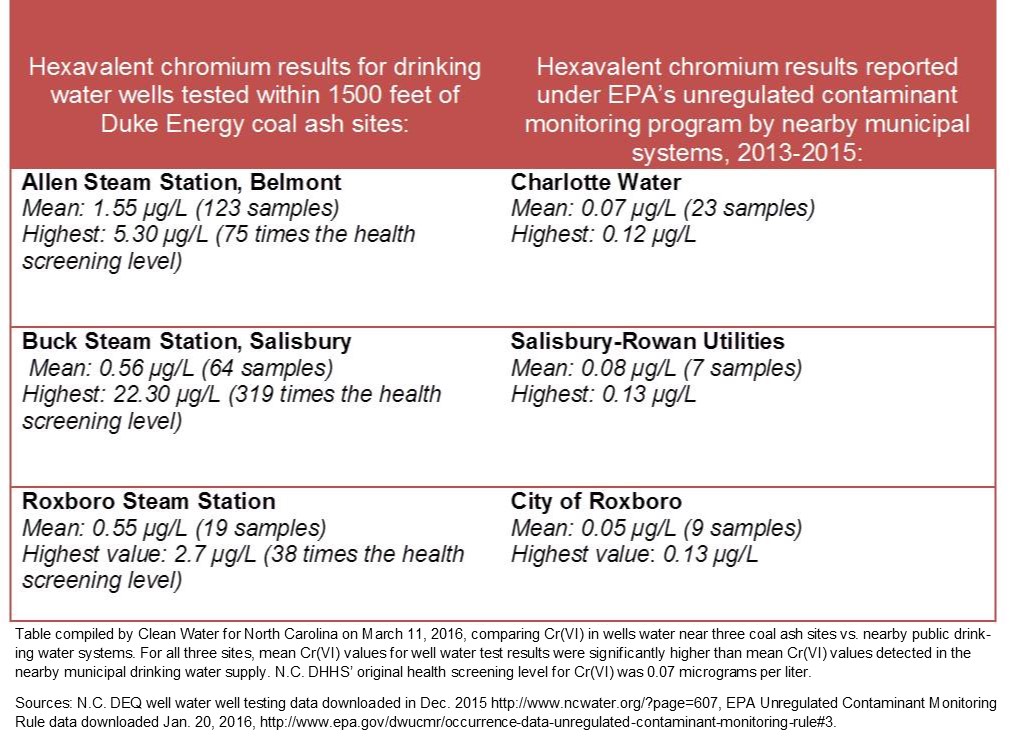

“While the amounts of hexavalent chromium detected in municipal water supplies in North Carolina are worrisome and show we do need state and federal drinking water standards to catch up to the latest science, some of the levels found in wells near Duke’s coal ash sites have been much higher,” said Katie Hicks, Associate Director for Clean Water for North Carolina.

Experts Disagree

The state began testing well water near coal ash dumps following the 2014 Dan River coal ash spill when the N.C. General Assembly passed the Coal Ash Management Act, or CAMA.

Duke Energy owns the coal ash dumps and began providing bottled water to residents under the CAMA rules after the well water test results were made public. A review of the relevant letters and public comments reveals both the state and company were aware of the test results for several weeks before residents were notified.

Duke Energy maintains that it is not responsible for the contamination.

State Health Director Randall Williams, MD, explained to the commission, on behalf of the state’s Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS), why its “do not drink” orders were being revoked:

We realized that as you looked around the country … that at least with vanadium, there was no regulation. And while there was regulation for chromium, it didn’t specifically say hexavalent [chromium] VIEPA that chromium could be made up of only hexavalent [chromium] VI.

Listen to Randall Williams’ testimony here.

Williams is an obstetrician and gynecologist, not a toxicologist, and he took his position with DHHS in July 2015, months after the “do not drink” orders were issued to residents. During his testimony, he noted that vanadium and chromium – though not hexavalent chromium – is found in vitamins.

It was only in the last 30 seconds of his 30-minute testimony that he stated that those who received “do not drink” orders under CAMA would be notified of the state’s revised decision.

Dr. Kenneth Rudo is a toxicologist who works with Williams in DHHS and is one of the scientists who helped establish North Carolina’s hexavalent chromium and vanadium health standards. In the past, he has publicly stated that the human body reacts differently to hexavalent chromium and vanadium when consumed via water.

Currently on leave, Rudo declined to comment for this article, instead referring me to Nancy Holt, an established expert on water quality and public health issues who is presently working with the Flint, Mich., community, and has worked with at least 30 other states during her 40-year career. She said:

What’s happening in North Carolina is similar to what’s happening in Flint. The water is not safe to drink, even if it is in municipal water supplies – it’s not safe. What’s happening now is about politics. I have never known a state to withdraw ‘do not drink’ orders. The only thing that is important is protecting people, and the state of North Carolina has withdrawn that protection. It’s the saddest thing I’ve ever seen.

State and Federal Standards

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s Safe Drinking Water Act, established in 1974, does not include a standard for vanadium. The agency’s standard for total chromium is 100 micrograms per liter, twice what it was prior to 1991. “Total chromium” includes both hexavalent chromium (chromium VI) and chromium IIIEPA’s standard for chromium is under review. The agency’s new standard is expected to be released in December 2016.

Not only is it confusing that government lumps two types of chromium together – one harmful and one beneficial – but the standards for chromium can be different for groundwater, treated municipal drinking water and well water, and they can be different in each state.

Following an investigation in the 1990s near a Pacific Gas and Electric plant — made famous by the movie “Erin Brockovich” — California established the nation’s first public health limit for hexavalent chromium at 0.02 micrograms per liter of drinking water. That standard was lowered to 0.01 micrograms in 2014. But a discovery of an exceedance of that standard only triggers a government warning to discontinue cooking with or drinking the water.

*Despite the lowered and unenforceable health standard, in 2014, California raised its drinking water standard for hexavalent chromium to 10 micrograms per liter; it now matches the EPA’s standard. The drinking water standard is enforceable by law.* [Correction 3/17/16: The EPA standard is actually 100 micrograms per liter — 10 times higher than CA‘s — and is for total chromium, which includes hexavalent chromium and chromium III. We regret the error and thank EPA for pointing this out after this article was first published.]

Still, should Californian authorities discover a citizen’s drinking water contains, say, 0.09 micrograms of chromium per liter – as was found in some drinking water wells in North Carolina – the state may advise the citizens not to use their water due to health concerns. Meanwhile, up to 10 micrograms is allowed to be present in public drinking water in both states before the government will take further action.

In 2015, N.C. DHHS established a state public health screening level for hexavalent chromium at 0.07 micrograms per liter in drinking water – seven times California’s standard. In North Carolina, the groundwater standard for hexavalent chromium is 10 micrograms per liter. It’s the state’s public health screening level that is being eliminated, and that is why the “do not drink” orders are being withdrawn.

For this article, DHHS staff was asked which state or private sector toxicologists were involved in the state’s decision to revoke the “do not drink” orders. They did not respond to multiple requests.

Public Health at Risk

In an email dated Feb. 16, 2015, a state health assessor for DHHS, Sandy Mort, MS, noted the state’s standards for chromium were “dated and no longer protective of public health.” She explained that hexavalent chromium poses “an unacceptable level of excess lifetime human cancer risk.”

It’s that “dated” standard that North Carolina is apparently now reverting to. According to state emails obtained via public information requests from state agencies, DEQ and DHHS are acting against the advice of numerous employees – including scientists and public health experts.

According to an article in The Salisbury Post, Rudo said: “Our rules require us to look at chemicals based on a one-in-a-million cancer risk.” Rudo has defended DHHS’ 0.07 public health screening level during public meetings and also when speaking privately to residents. At the meetings — and according to several residents who communicated with Rudo — he has maintained that not only would he avoid drinking the contaminated well water but that he wouldn’t give it to a dog.

“The North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services performed Health Risk Evaluations (HREs) on 360 wells pursuant to CAMA,” Alexandra Lefebvre, a public relations representative for DHHS explained in an email. “Of these, 330 exceeded the screening levels for one or more constituent and the HRE recommended that the water not be used for drinking or cooking.”

According to Lefebvre, of those, 95 of the “do not drink” orders will stand either because their well water contained hexavalent chromium, vanadium and some other contaminant — like arsenic, cobalt, manganese, lead, or iron — or, their well water contains one of those other constituents but not hexavalent chromium or vanadium.

In January 2016, DEQ’s Reeder reported to the N.C. Environmental Review Commission (ERC) that 424 North Carolina households were ordered to avoid their water.

North Carolina’s decision to revoke its “do not drink” orders precedes a “Report on the Study of Standards and Health Screening Levels for Hexavalent Chromium and Vanadium” due on April 1, 2016, to the state’s ERC and the Joint Legislative Oversight Committee on Health and Human Services.

The state’s announcement comes in the middle of a month-long series of statewide public hearings regarding priority rankings for Duke Energy’s coal ash impoundments and three days after the Department of Environmental Quality issued 12 violation notices to the company for “unauthorized discharges of wastewater” near the company’s coal ash impoundments.

Duke Energy owns 14 coal plants in North Carolina and all of the coal ash dumps that are subject to North Carolina’s priority rankings. A site’s ranking determines how quickly, or if, a site will be excavated and the ash moved to a lined, monitored landfill.

A “low priority” ranking would allow the company to cap the dumps with a synthetic cover, clay, and grass then leave it in place, despite evidence that groundwater is already contaminated near each site. The company will continue monitoring the groundwater near the coal ash dumps, whatever their priority ranking, and submit those reports to the state.

Unwelcome News

Duke Energy public relations representative Paige Sheehan said the company will continue delivering bottled water for the time being and that Duke had offered bottled water to provide citizens with “peace of mind.”

“[The state’s withdrawal of ‘do not drink’ orders] is certainly welcomed news to well owners, but it’s terribly unfortunate the state took almost a year to give them certainty that their water is safe to drink,” Sheehan wrote in an email.

Amy Brown says the state’s decision to revoke her “do not drink” order is not welcome news. She does not have “peace of mind.”

“How can I use this water after I was told a year ago that my water was unsafe? How can I erase a whole year of fearing my faucet?,” Brown told me.

Rhiannon Fionn is an independent investigative journalist and filmmaker in post-production on the documentary film “Coal Ash Chronicles.”

Photo credits: Down East Coal Ash Coalition

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts