Australia’s new Prime Minister, Malcolm Turnbull, is probably the nearest the country’s conservative ranks have to a climate hawk.

During his short ten years in public office as a member of the Liberal Party, Turnbull has been a staunch defender of climate change science and an advocate for tackling rising greenhouse gas emissions as a “risk management” issue for the planet.

Late Monday, Turnbull challenged Tony Abbott for the leadership of the Liberal Party and within half a day, had been voted the new leader, 54 to 45.

Turnbull may not be as as comparitively hawkish as US President Obama, but given the bar is so low among Australia’s conservatives, Turnbull should be seen as the best of a pretty terrible bunch on climate science and policy.

With the arrival of Turnbull, Australians can now at least assert that they’re no longer led by someone who once said climate science was “absolute crap” and who denied warming temperatures increase the risk of bushfires and who told his citizens that “coal is good for humanity.”

But what might Turnbull’s arrival mean for climate policy in Australia? And, in particular, what will it mean for Australia’s position heading into international climate talks in Paris in less than three months time?

On the first of those two questions, it is really too early to tell with his leadership position less than 24 hours old as I write.

But campaigners are hoping the shift in leadership will mean Australia can develop a clearer position on a transition away from its heavy reliance on fossil fuels.

Under Abbott, the government had taken obstructive positions on renewable energy.

For example, the Treasurer Joe Hockey (who is likely to be replaced) had ordered the AU$10billion Clean Energy Finance Corporation to stop investing in wind energy and small scale solar projects. Could Turnbull look to withdraw that ministerial request?

Turnbull has historically been heavily critical of the government’s centerpiece climate policy — an Emissions Reduction Fund (ERF) that uses taxpayer dollars to pay companies with projects to cut their emissions.

But in his first speech as the new Liberal Party Leader, Turnbull said that the ERF climate policy would remain. But he no doubt is well aware that credible analysts have said the policy is inadequate and is unlikely to deliver even the weak cuts proposed by Australia domestically.

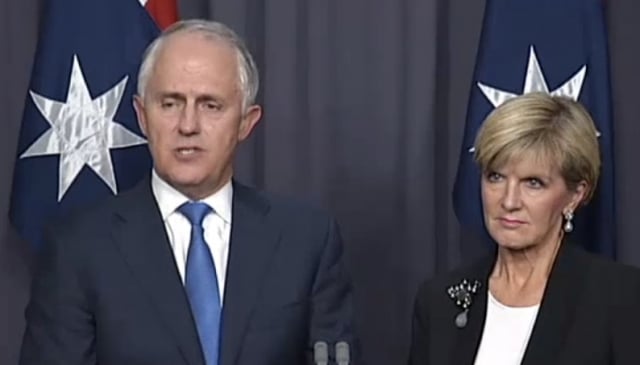

Many political commentators have noted the significance of the role of Deputy Prime Minister Julie Bishop (pictured) in Turnbull’s success overnight.

Bishop was the senior Australian minister sent to Lima to negotiate at the last major climate talks — albeit with a chaperon in the guise of Trade Minister Andrew Robb, a situation which infuriated Bishop.

Turnbull’s rise may give Bishop more room to move in those Paris negotiations (presuming Turnbull decides against going to Paris himself and does send Bishop… there are a lot of ‘if’s).

While Bishop will still have to arrive in Paris holding the country’s weak domestic reductions target, the backing of Turnbull might remove a little of the stench of climate science denial and fossil fuel advocacy that has been hanging around Australia at previous talks.

Certainly, the risk of Australia acting as a blocker at the Paris talks are reduced under a Turnbull government.

In late 2009, Turnbull was the Liberal Party leader in opposition. He was challenged primarily because of his backing for policy that would put a price on greenhouse gas emissions. He lost by one vote to Tony Abbott.

At the time, Turnbull said: “I will not lead a party that is not as committed to effective action on climate change as I am.”

Some six years and five Prime Ministers later (if we count Turnbull himself), the question is how committed is Turnbull to cutting greenhouse gas emissions and how closely does his idea of “effective” policy match the science he has defended in the past?

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts