Labour’s climate policies depend on carbon capture and storage to provide energy and jobs, despite serious concerns about the practice.

Coal burning will power Britain under a Labour government through the use of carbon capture and storage (CCS), the shadow secretary of state Caroline Flint has confirmed.

The controversial practice of producing power and then offsetting the carbon emissions by burying the CO2 underground would be a pivotal part of Labour’s energy policy, added Flint.

Speaking at an Energy UK-sponsored fringe meeting during the Labour Party Conference in Manchester this week, the Doncaster MP said: “There is a future for coal mining, and that’s why we’ll make sure carbon capture and storage is part of that journey.”

“The benefit that arose out of the Climate Change Act in 2008 is that we can really reap the advantages of knowing what it is all about, and invest in the jobs that come with that.”

She returned to the issue during a Prospect magazine fringe meeting on the final day of the conference. She confirmed after a question from a representative from the Friends of the Earth group that coal would only be used within a CCS scheme beyond 2020.

She said: “I’m a Doncaster MP. A hundred years ago, it was a hamlet. People dug a great big bloody hole in the ground and created coal mining.”

She went on to enthuse about the capabilities of CCS later in the conference. “CCS isn’t something that is just used for coal plants,” she said. “It can also work for gas too, and would help our energy-intensive industries as well.”

This is not the first time that Flint has endorsed CCS as a viable energy alternative. In July this year, she set out her stall, saying that: “The Labour party is clear – as we shift to a low carbon economy, CCS is a necessity, not an option.”

The Parliamentary Committee on Climate Change has advised the government that CCS is needed for Britain to meet its targets and still burn gas as late as 2030. The Tory-led coalition government recently agreed £100 million in funding for two demonstration projects using CCS. The European Union has promised a further €300 million for development.

However, CCS is yet to prove successful on an industrial scale and may turn out to be prohibitively expensive.

Expensive, High Risk

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change released a special report on CCS which suggested that the technology could double the cost of generating energy through burning coal.

Robin Lovelace and Luke Temple, academics from the University of Leeds, have argued that CCS could even boost CO2 output. They say: “CCS is expensive, high risk, and may actually increase emissions due to greater demand for coal.

“These technical drawbacks alone suggest that the government’s commitment to CCS does not add up. Cheaper and more reliable options exist, yet these rarely enter the debate.”

Researchers working for the environmental campaigners have issued a detailed report which asserts that “carbon capture and storage won’t save the climate”.

The report states that CCS uses 10–40% of the energy produced by a power station, and that the safe storage of CO2 cannot be guaranteed—even very low leakage rates could undermine any climate mitigation efforts.

The CCS “journey” has involved serious setbacks. The very first CCS plant was announced for development at Peterhead in Scotland in 2005, but was cancelled just two years later.

Two further CCS projects were announced for Kingsnorth and Longanet in 2010 only to be scrapped within a year. Ayrshire Power abandoned its plans to build a coal plant with CCS at Hunterston in Scotland after 22,000 objections were made about the planning application.

Richard Dixon, the director of WWF Scotland, said at the time: “The last thing we need is a new coal-fired power station hiding behind a green fig leaf.”

In the United States, the Department of Energy abandoned plans for a CCS power plant in Illinois when the the expected costs escalated beyond $1.8 billion.

Clean Coal

Despite these concerns, Labour is still risking its climate promises by gambling on CCS. This has long been the party’s policy. Ed Miliband previously backed CCS when serving in the Labour government as secretary of state for energy and climate change. He promised an era of “clean coal” in 2009.

Miliband said: “There is no alternative to CCS if we are serious about fighting climate change. We need new coal-fired power stations [for energy security], but only if they can be part of a low carbon future.”

“With a solution to the problem of coal, we greatly increase our chances of stopping dangerous climate change emissions. Without it, we will not succeed.”

Flint has also hinted that shale gas fracking could play a part in Labour policy. She wrote in the October issue of Prospect: “Labour is committed to the decarbonisation of our electricity supply by 2030… We still need flexible power to help manage peaks in demand.”

She added: “In 2004, the UK became a net importer of gas for the first time since North Sea extraction began. For those reasons, there are potential benefits to shale gas, if it can be extracted safely in a context of robust regulation, monitoring and local consent. It could help displace some imported gas, thereby enhancing the UK’s energy security.”

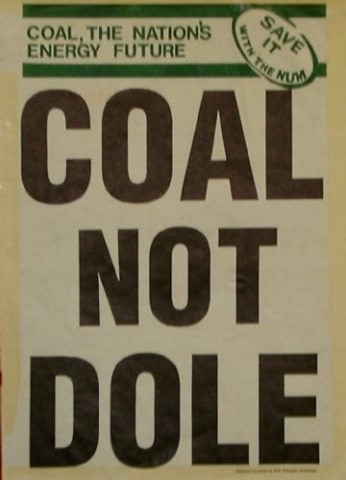

During the year-long miners’ strike of 1984, one of the most popular chants was “coal not dole”. The slogan appeared on hundreds of thousands of badges 30 years ago. Climate change at that time was not a political issue.

Some of the left-wing radicals and trade unionists on the marches wearing the badges are today accused of advocating “dole not coal”, when in fact they are demanding a million climate jobs be created.

ADDITIONAL REPORTING: HELEN NIANIAS

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts