This weekend in The Washington Post, two deans of the Washington establishment, the Brookings Institution’s Thomas Mann and the American Enterprise Institute’s Norman Ornstein, finally stated what has been increasingly obvious: The problem with U.S. politics is coming from the right, not from “both sides.” In their piece, provocatively titled “Let’s Just Say It: The Republicans Are The Problem,” they note that Republicans and conservatives have become extreme and unwilling to compromise. And as they stress, this is not something the Democrats or liberals are “just as bad” at.

Hence, the whole approach of the mainstream or centrist media is myopic or, worse, complicit. “A balanced treatment of an unbalanced phenomenon distorts reality,” write Mann and Ornstein.

Mann and Ornstein make allusion in their piece to the fact that conservatives have simultaneously become extremely anti science (witness climate change) and anti empirical. And indeed, when it comes to eschewing phony media balance, well, that’s something we science journalists have been recommending for a decade. In this, we’ve been way, way ahead of the game. We’ve had to be.

Mann’s and Ornstein’s piece is very important and a breath of fresh air; yet in truth, their approach is probably still too centrist. The problem is that their analysis is purely sociological and historical in nature—in some cases blaming Republican extremism on the actions of a few individuals, like Newt Gingrich and Grover Norquist–rather than psychological.

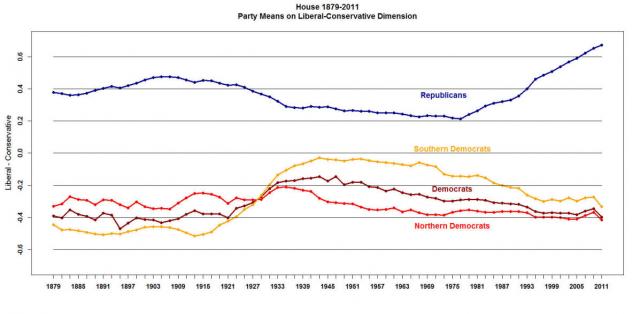

Consider, for instance, some important new data (pictured here, click link to enlarge), cited by Mann and Ornstein, showing that House and Senate Republicans have become much more ideological over the past 30 years, whereas Democrats and liberals have not. That’s true and revealing, but why is it occurring?

Nowhere in Mann’s and Ornstein’s article (though perhaps it is in their new book) does one find a discussion of the phenomenon of psychological authoritarianism. According to an extremely important 2009 book by political scientists Marc Hetherington and Jonathan Weiler—Authoritarianism and Polarization in American Politics—the chief reason for what Mann and Orenstein are lamenting lies in this psychological phenomenon.

As I explain in The Republican Brain (which cites Hetherington and Weiler), authoritarianism means seeing the world in black and white. It means refusing to compromise. It means being intolerant of ambiguity and uncertainty, and needing order and structure.

Authoritarians tend towards right wing politics and fundamentalist religion. They tend toward belief affirmation and ideological rigidity, rather than exploring new ideas or considering that other sides might have valid perspectives. For authoritarians, there is only one way of doing things, one right way—and one’s opponents are weak and absolutely wrong.

A wealth of social science data, presented in Hetherington and Weiler’s book, suggest that in the U.S., the Republican Party and the conservative movement have become increasingly authoritarian. So this is what Mann and Ornstein are really writing about, though they don’t acknowledge it.

Furthermore, this explains the growing gulf between the Republican Party and the “reality based community.”

Authoritarian styles of thinking are deeply inimical to scientific reasoning—one might even call the two cognitive styles natural enemies—which is why we now see so much denial of science and reality on the right. If you believe you’re absolutely right, and your opponents are absolutely wrong, then of course you’re willing to dismiss a large body of evidence against you as a conspiracy–as we now see in the climate change arena.

So give Mann and Ornstein about three stars out of four. Finally, centrist Washington observers are starting to acknowledge what is really going on out there. But they haven’t opened their minds yet to the full ramifications of their observation.

It is very likely that authoritarianism reflects a part of human nature that exists across countries and across time. It takes different forms in different contexts, and can be activated, or suppressed, by particular circumstances. But in no case is it what you might call a friend to science–which fundamentally requires the toleration of different viewpoints along a bumpy road towards more accurate understanding, and a better society.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts