Depressing doesn’t even begin to capture it.

On the one hand, scientists have become increasingly certain that climate change is real and human caused. They’re now saying “very likely,” a degree of certainty equivalent to greater than 90 percent.

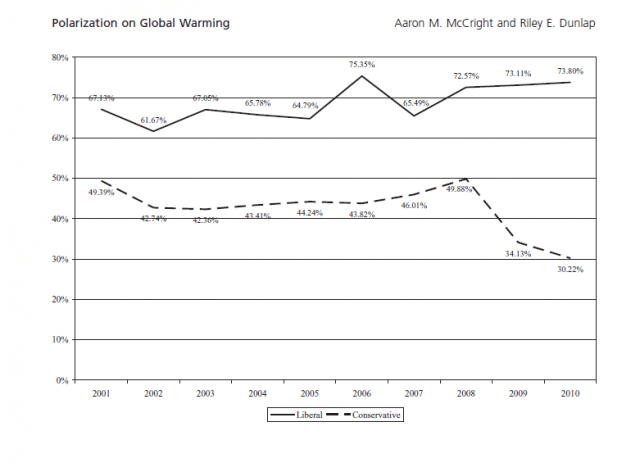

Yet at the same time, the two U.S. political parties have grown increasingly polarized over whether to accept this fact about the world. There’s now a 30 percent gap between Democrats and Republicans in their likelihood of believing the above to be true. This gap has widened, even as scientific doubt has narrowed.

That’s the finding of a comprehensive new study (press release here) on our polarization over climate change by Aaron McCright of Michigan State and Riley Dunlap of Oklahoma State. They looked at 10 years of Gallup polling on the issue, and found a steady march in opposite directions for the two parties. Or as the authors put it: “Moving from the right to the left along the political spectrum increases respondents’ likelihood of reporting beliefs consistent with the scientific consensus and of expressing personal concern about global warming.” That’s academic speak, so they didn’t add on the following next sentence, as I would have done: “A lot.”

But that’s not the only thing McCright and Dunlap looked at. They wanted to examine another issue as well, based on the data: Did the divide over climate change have anything to do with citizen educational attainment or self-expressed understanding of the issue? After all, this is a scientific topic. You’d expect those who understand it better to believe the science more, regardless of party.

But a number of studies have suggested this is not the case if you’re a Republican or conservative, and the sweeping new analysis of McCright and Dunlap confirms this as well. Or as they put it, after crunching the data: “The effects of educational attainment and self-reported understanding on beliefs about climate science and personal concern about global warming are positive for liberals and Democrats, but are weaker or negative for conservatives and Republicans.”

How did we get to such a point—where ideology and party identity not only strongly predict whether you accept science on a critical issue, but also whether your level of education or understanding will make matters better or worse?

McCright and Dunlap have important ideas here as well. They postulate that underlying ideologies about how society should be run, the benefits and costs of industrial capitalism, and whether the market should be regulated, predict different dispositions towards climate change science–but also that the way we currently receive information about the issue reinforces polarization. Let’s give them the last word on this (ever depressing) front:

New information on climate change (e.g., an IPCC report) is thus unlikely to reduce the political divide. Instead, citizens’ political orientations filter such learning opportunities in ways that magnify this divide. Political elites selectively interpret or ignore new climate change studies and news stories to promote their political agendas. Citizens, in turn, listen to their favored elites and media sources where global warming information is framed in a manner consistent with their pre-existing beliefs on the issue (Hindman 2009).We believe this occurred within the American public between 2001 and 2010, and our results seem to bear this out.

Yes, indeed. Motivated reasoning, anyone?

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts